Insights

Into Housing and Community

Development Policy

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Ofce of Policy Development and Research

Assessments of Shared Housing in the United States

Shared housing, generally defined as a living arrangement in which two or more unrelated people share a house or apartment, is

an affordable living arrangement in the United States, particularly in urban areas with high housing costs. Shared housing ranges

from home sharing, where a homeowner rents out a room in the owner-occupied property to a person seeking affordable housing,

to co-living, where an individual rents a private room in a single-family or multifamily building but shares common areas with other

tenants. Shared housing can take different forms, and many U.S. and international shared housing organizations and companies

facilitate shared housing arrangements or build formal shared housing developments.

Shared housing arrangements can vary from short-term, transient housing to long-term, permanent housing. The range of possible

setup options means that shared housing can benefit many people, including those new to a city; those in search of affordable housing

who may not qualify for or receive housing assistance; transient workers in need of housing while working on a contract; senior

homeowners looking for long-term assistance to age in place; individuals wanting to live communally in an “intentional community”;

families living in multigenerational arrangements; or homeowners simply wanting to reduce their housing cost burden. Indeed, the

different shared housing models can offer flexibility for individuals not ready to commit to long-term housing solutions or for those

wanting to save money for other housing options.

Shared housing can provide greater flexibility for a housing stock to meet current market demands by housing more people in

a housing unit. High demand for housing in urban areas reduces the availability of affordable housing, increasing the price for

housing and the housing-cost burden of residents in those areas. Housing affordability may be further reduced by restrictive building

regulations and zoning codes in these areas, among other factors. In response to increasing housing costs, many people share housing

to reduce their housing-cost burdens. Individuals living in shared housing weigh a variety of tradeoffs when deciding whether to share

housing—including their willingness to pay—with preferences over privacy, communality, types of space, amounts of living space,

and location, among other hedonic influences. Some individuals, facing economic constraints, choose to share housing because of the

relatively lower housing cost compared with living alone, and yet others prefer to share housing regardless of price factors.

The paper finds that there are many different types of formal and informal shared housing arrangements, and that they can offer

a range of benefits to residents, including reduced social isolation. They allow for flexibility in a housing stock and can allow

individuals to live in more opportunity-laden locations, especially in times or areas where housing supply is more constrained. Two

of the more common types of shared housing are home sharing and co-living; home sharing is a way for homeowners to reduce their

housing costs and provide an affordable housing option to others. Formal co-living models, reinforced through the design of housing

built specifically for co-living, are a rapidly growing sector of real estate markets, because they present a convenient way for young

professionals to move to and live in a new city, often in communities nearby to desirable urban amenities and places of employment.

Many cities and states in the United States and other countries are embracing shared housing models, through regulatory reform of the

built environment to allow these arrangements and pilot initiatives of shared housing designed for particular populations, including

low-income tenants, formerly homeless individuals, and other underserved households. Across different measures, there has been

a small increase between 2000 and 2019 in the prevalence of households who share housing. Depending on the expansiveness of

the definition for shared housing, the current rate of shared housing is somewhere between 3 and 20 percent of all housing units.

Moreover, there are a substantial number of homes which might be called “undercrowded”, with 26 percent of homes having two or

more bedrooms per person in the household. This suggests a potential capacity for greater shared housing.

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

2

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

This paper offers an overview of shared housing in the United States from both a theoretical and a practical standpoint. Overall, it

addresses what shared housing is, examines which households live in shared housing arrangements and why, and discusses the various

shared housing models available in the United States—including organizations that either directly provide or facilitate (often matching

prospective tenants to providers) shared housing options. Section 2 gives a brief history of shared housing in the United States; details

some of the economic, social, and health-related factors that play a role in the behavior of individuals who choose to share housing;

and analyzes indicators showing the prevalence of shared housing in the United States. Section 3 describes the models and challenges

of home sharing and co-living in the United States in more detail and draws on qualitative interviews that U.S. Department of Housing

and Urban Development (HUD) staff have conducted with leading home sharing and co-living firms. Section 4 provides examples

of federal and state initiatives in shared housing, including allowances for shared housing as an alternative living arrangement that

assisted residents can use in HUD’s Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program and specific international research partnerships around

shared housing between HUD and foreign governments.

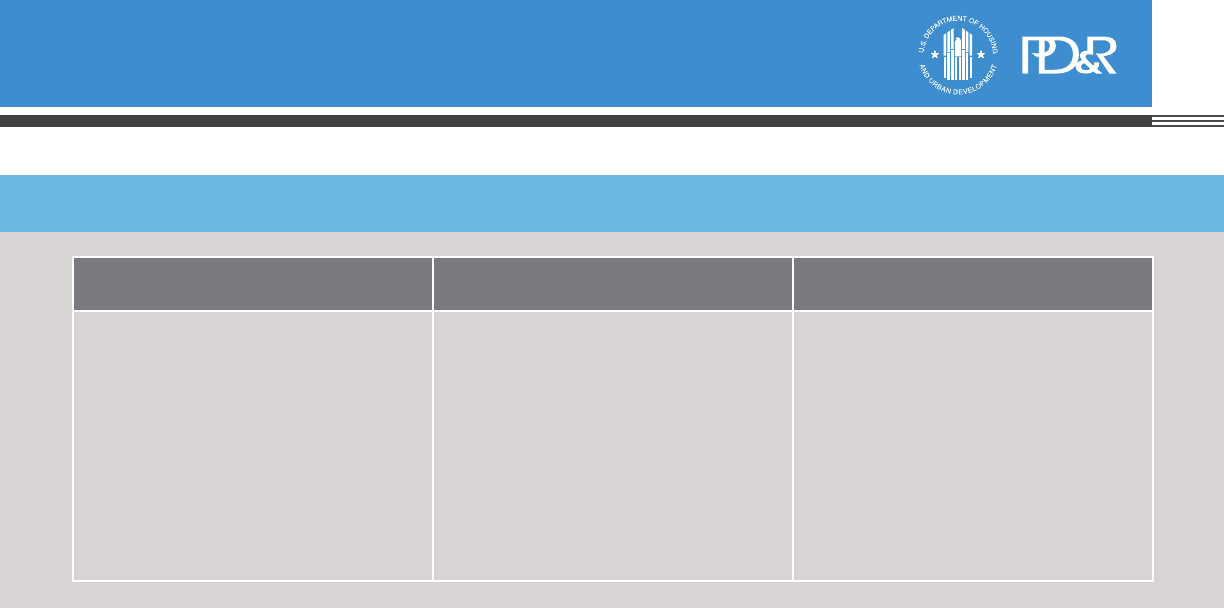

Same Housing Unit Same Building

Flat Share Unrelated roommates, often from the same

generation and without children, living

in the same house or apartment unit.

Typically with individual bedrooms but

sharing common spaces, including kitchens

and baths

Co-Living Individual renting of private and often

furnished rooms, typically in multifamily

buildings, with shared common spaces in

individual units and in buildings. Frequently

targeting adult professionals in high-demand

housing markets

Multigenera-

tional

Household

Related or unrelated household with two or

more adult generations

Single-Room

Occupancy

(SRO) housing

Affordable housing designed for low-

income tenants renting small and sometimes

furnished single rooms, with shared kitchens

and baths in the building

Home

Sharing

Renting out of homes by resident

homeowners in exchange for services,

typically senior homeowners looking for

support to age in place

Co-Housing Private, individually amenitized, self-

contained units or homes clustered

around shared space to form intentional

communities, which can be organized

formally as a homeowner’s association or

housing cooperative

Group Home Private home for individuals needing social

assistance, such as drug rehabilitation,

often with an on-site resident manager

Figure 1. A Typology of Shared Housing

Why Do People Share Housing?

Shared housing is a unique housing

design and living arrangement that

residents pursue formally or informally

for a variety of reasons. In the United

States, single-room occupancy (SRO)

housing exemplifies a visible form

of shared housing that rose with

industrialization and urbanization and

declined with the suburbanization

of American housing. In today’s era

of “reurbanization” of American

cities—as seen from an upward trend

in population growth starting in some

cities in the 1980s

1

—both renters

and homeowners live in many

other types of shared housing

arrangements and are motivated to

do so generally by some combination

of economic, social, and health-

related factors. Some of these factors

are detailed below.

3

Although SROs

remain an important

form of shared

housing for certain

housing users, shared

housing has expanded

to cover many other

types of housing.

History of Shared Housing

Shared housing has been a common

housing arrangement throughout U.S.

history. Early co-living concepts can be

traced back to the early 19th century

in the form of single-room occupancy

buildings and boarding houses in large

urban areas.

2

These shared housing

models offered affordable housing

for people who came to urban areas

to work. As metropolitan economies

grew, however, overcrowding led to the

perception and proliferation of unsafe

conditions in boarding houses in many

urban areas, and as safety regulations,

building codes, and occupancy limits

became commonplace, these housing

arrangements either became tightly

regulated or were largely outlawed by

states and localities. SROs began to

wane in the 1920s, and single-family

homeownership became increasingly

prevalent after World War II with the

cheap production of housing, increasing

incomes, the development of American

suburbs, and the promotion of the nuclear

family

i

as a social norm.

3

Many SROs were

demolished or converted into other uses,

like offices or hotels. Research has paired

the reduction in SROs, which was often

politically motivated,

4

with increases in

homelessness and the use of motels and

hotels as informal housing for low-income

renters with limited social capital.

5

Technological advancements in the

construction industry

6

,

7

(especially

i

Generally defined as a couple and their dependent children, which is regarded as a basic social unit.

around fireproofing

8

and ventilation

9

),

regulatory reform,

10

and advancements

in public health

11

mean that it is now

possible to build dense housing with

lowered minimum unit sizes without

creating unsafe and unsanitary habitation.

Although SROs remain an important

form of shared housing for certain

housing users, shared housing has

expanded to cover many other types

of housing. Some of the most common

types are detailed in Figure 1 and can be

differentiated based on whether residents

are sharing the same housing unit or the

same building. Many shared housing

arrangements, such as home sharing

and co-living, are becoming increasingly

common, as can be seen through the

establishment and growth of these

models in the formal real estate sector.

Many shared housing

arrangements,

such as home

sharing and co-

living, are becoming

increasingly

common, as can be

seen through the

establishment and

growth of these

models in the formal

real estate sector.

Economic Factors for

Shared Housing

Shared housing enables people to live

more affordably by reducing their

housing costs; shared housing most

often occurs in metropolitan areas

with high housing costs. Of course,

shared housing is not for everyone:

people have different preferences in

their housing arrangements based on

many factors, like proximity to work;

family needs; and preferences around

amenities, individual space, and privacy.

Hedonic pricing studies of shared

housing in the form of Airbnb rentals

(attempting to measure the contribution

of various internal and external factors

to the housing price) found that, across

cities, individuals were willing to pay

an additional premium for rentals that

were listed as an “entire home” or “entire

apartment” as compared to a private

room or shared room, holding other

factors constant.

12

,

13

This finding shows

that the norm may be for people to

willingly pay more for privacy; however,

these preferences may be limited by

a person’s income, wealth, and how

much they can afford to spend on

housing costs. As a person ages, these

preferences can change as well. Many

people who can afford the option of

living alone prefer the privacy and

autonomy that living alone provides.

The financial situation of many people

living in high-cost areas, however, may

not enable them to live alone in preferred

locations near their jobs or other desired

amenities, such as public transportation,

safety, entertainment, and other amenities

associated with well-served urban areas.

Shared housing provides a way to reduce

housing costs while still living in a more

preferred area. Indeed, shared housing

represents a tradeoff in preferences

between privacy and the opportunity

to live in a higher-quality home or

neighborhood than an individual or

family could afford on their own. A survey

of welfare-assisted families in unassisted

private housing in the state of Virginia,

for example, found that living in shared

housing, as opposed to living alone, was

associated with reduced rent burden and

better physical housing quality.

14

Figure 1. A Typology of Shared Housing

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

4

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

Shared housing

represents a tradeoff

in preferences

between privacy

and the opportunity

to live in a higher-

quality home or

neighborhood than

an individual or

family could afford

on their own.

Reasons for “doubling up” or sharing

housing vary individually but come

down to some tradeoff between social

and economic factors.

15

Economic

factors include housing costs, income,

expenditures, other expenses, and a

person’s ability to pay for a housing unit.

Research on home sharing indicates that

economic factors are the main motivating

factor for shared housing.

16

Evidence from

Zillow suggests a relationship between

the unaffordability of rental markets and

“doubling up” behavior. For instance, in

2017, Los Angeles had the highest share

of adults living with roommates or adult

parents (50 percent), while also being the

third most expensive rental market in the

country.

17

Interviews with shared housing

organizations indicate that economic

factors are the primary reason people

share housing.

18

Lifecycle factors—such as age, marriage,

and having children—also influence

a person’s housing preferences.

Traditionally, young adults rent

housing until they have accumulated

enough wealth or until they marry, at

ii

The costs associated with homeownership also play a role, including the downpayment and ongoing maintenance. Research points to wealth and income as some of

the largest barriers to homeownership, particularly because of the large upfront cost in the form of a downpayment. Despite the link between homeownership and the

building of wealth in the long run, owning is generally more expensive than renting, so financial constraints can be a barrier to homeownership and influence a person’s

decision on whether to rent or own, and whether to live alone or share housing. Shared arrangements make housing more affordable by reducing housing costs for the

individuals involved.

iii

Manhertz, Treh. 2020 “Almost 3 Million Adults Moved Back Home in Wake of Coronavirus.” Seattle, WA: Zillow. https://www.zillow.com/research/coronavirus-adults-

moving-home-27271/. Analyzing CPS data, Zillow research analysis reports that roughly 2.7 million adults moved in with a parent or grandparent in March and April of

2020. About 2.2 million of the adults were between 18 and 25 years old. The Zillow article notes that the living situation of this age group fluctuates in normal times, and

the volatility of their living situation is exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic due to uncertainties in labor markets and of in-person attendance at universities.

which point they may have increased

their income or accumulated enough

wealth to afford the upfront costs of

homeownership.

ii

Renting also provides

people with flexibility to move for

employment or other reasons, whereas

homeowners are frequently tied to their

area of residence. Moreover, the ability

for shared housing to foster the sharing

of childcare gives mothers more time to

invest in their own human capital and

improve their economic position

19

—key

factors for consideration in addition

to preferences for proximity to work,

family, and amenities.

Sharing housing is also a viable option for

those experiencing economic insecurity

who need a place to live. After all, if

an individual’s income is impeded due

to a job loss, shared housing can help

alleviate the financial burden of housing

costs by sharing that cost with family

or others. Economic downturns appear

to influence the rate of shared housing.

For instance, according to the U.S.

Census Bureau, the number of shared

households increased during the Great

Recession.

20

A 2012 Census report

found that in 2007, 13.9 percent of

households, or 31.0 million households,

included an additional adult; in 2010,

that percentage increased by 3 million

households to 34.5 million households,

or 15 percent of all households. Of the

roughly 31 million households that

included an additional adult in 2007, 2.4

percent, or 5.3 million households, were

households with an unrelated adult, and

those figures increased to 2.7 percent,

or 6.3 million households, in 2010.

Most commonly, the additional adult in

a household was a relative or child of

the householder. These changes show

that macroeconomic conditions can lead

individuals to share housing to reduce

housing costs, and that they will often

double up with family members first.

iii

Social Factors for

Shared Housing

Although economic factors are the

primary motivator for people sharing

housing, there are many social benefits

to consider in shared housing, including

companionship—whether in the form

of a housemate, a cohabitating partner,

a relative, or a marriage. Most residents

of shared housing report having at

least occasional social events with the

participation of the full household.

They report emotional support and

companionship as the best aspects about

living in a shared house, and a lack of

privacy, a need to compromise or restrict

lifestyles, and having to cope with other

housemates’ moods as the worst.

21

Living

with someone can increase social support

and interaction; this increase can reduce

loneliness, which can have positive health

effects.

22

Research indicates that loneliness

is associated with reduced overall well-

being, including both poorer physical

and mental health.

23

In a 2010 study, He, O’Flaherty, and

Rosenheck questioned why shared

housing arrangements were uncommon

or discouraged policy responses for

formerly homeless people or people

at risk of homelessness, and whether

there were any adverse effects to

sharing housing.

24

In doing so, they

analyzed data from the Department of

Health and Human Services’ Access to

Community Care and Effective Services

and Supports (ACCESS) program, a

5-year demonstration program meant to

identify and evaluate the effectiveness of

integrated service systems for homeless

populations with serious mental

5

illnesses.

iv

They found that shared

housing did not negatively impact

participants’ mental health.

25

According to interviews with shared

housing organizations, homeowners

participating in shared housing programs

are often senior citizens living alone.

26

Due to ties to one’s home and community,

most senior homeowners want to age

in place, even if their homes cannot

meet their physical needs.

27

In many

cases, these seniors benefit from shared

housing arrangements, not only because

of reduced housing costs, but also

the additional companionship, social

interaction, and assistance with needs.

28

One study of home-sharers found that

residents aged 70 and above with a

roommate reported better health across

multiple dimensions, including sleeping

and eating better, feeling happier,

increased physical activity and energy

levels, and worrying less.

29

In many cases,

seniors benefit from

shared housing

arrangements, not

only because of

reduced housing

costs, but also

the additional

companionship,

social interaction, and

assistance with needs.

Like any other housing arrangement,

however, shared housing requires

compatibility among the individuals

involved. Clashes in personality, work

schedules, lifestyles, and noise levels can

iv

The ACCESS (Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports) program was a 5-year demonstration that evaluated the impact of integrated services on

outcomes of homeless people with severe mental illness. The program took place from 1994 to 1998 and was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services. The program provided funding and technical assistance to experimental and control sites in nine different states and provided funding for outreach and

services at each site. Data was collected on participants at entry into the program and 3 and 12 months later. Outcome data was collected from 7,055 participants. For

more information on the ACCESS program, see: https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.945.

lead to conflicts between individuals

in shared housing. Indeed, one must

consider many social factors when living

with another person. These arrangements

are based on the trust between the

individuals involved. This trust includes

the safety of the participating individuals

and the property and the commitment of

the individuals to pay their portion of the

housing costs and split the labor for any

domestic chores.

Trust is crucial in

managing conflict.

Trust is crucial in managing conflict.

Conflict can arise from power imbalances

(between resident owners and tenants) or

when tenants have different expectations

for the household. Qualitative research

has shown that individuals who have

a greater commitment to sharing, did

not choose to live in shared housing

solely for financial reasons, and

approach shared housing lifestyles with

a willingness to compromise, are better

at managing conflict.

30

The quality of

relationships and the way in which

residents choose to engage in them

can greatly affect the social and health

benefits of sharing housing.

31

The quality of

relationships and the

way in which residents

choose to engage

in them can greatly

affect the social and

health benefits of

sharing housing.

Importantly, shared housing

organizations often take on the burden

of trust in some form by vetting

participants, arranging interviews

between participants, following up with

participants, and acting as mediators in

case of conflict. Digitalization and the

advancement of technology have also

led to the capacity for individuals to vet

new tenants; this practice lowers the

risk of introducing an individual into a

space who has different household and

lifestyle expectations, but can also lead

to discrimination.

32

Digitalization can

also facilitate the logistics of independent

house sharing and remove barriers to

contractual obligations, such as splitting

utility bills.

Health Factors for

Shared Housing

Social relationships are a major benefit

of shared housing and can mitigate the

substantial negative health effects that

often accompany social isolation and

loneliness. A meta-analysis of studies

examining the connection between

loneliness and health found increased

mortality rates among those reporting

loneliness, social isolation, and living

alone.

33

Mechanisms for this increased

mortality risk include poorer health

behaviors when living alone, like poorer

sleep, physical inactivity, and smoking.

Being part of a social network at home

is associated with conformity to certain

social norms around health and self-

care. Having social relationships can

also provide individuals with self-esteem

and greater purpose. Additionally, the

decreased social isolation associated with

shared housing can reduce the risk of

domestic violence.

34

,

35

Health benefits can also stem from the

economic benefits of shared housing.

36

Cost savings derived from shared housing

can free up expenditures for families in

shared households to invest in better

food and in necessary medical costs,

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

6

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

both preventive care and direct treatment.

37

Studies have found that shared housing can

better support children with health issues

ranging from asthma to malnutrition.

38

An array of economic and social factors

influence the positive impact that shared

housing can have on residents’ health.

Health Considerations for Shared Housing During a Public Health Emergency

Shared housing can be associated

with negative health impacts if

it results in overcrowding. This

association is especially pertinent

given the time of publication, where

the COVID-19 pandemic continues

to affect the way of life across the

world, and, by some metrics, seems

to be spreading more quickly in

areas with higher residential density.

The connection between disease and

density, however, is not immediately

obvious. With COVID-19, some rural

recreation areas in the United States

have seen similar rates of infection

spread as in dense urban areas.

The geography of socioeconomics

also plays a large role. According to

urbanist Richard Florida, “There is a

huge difference between rich dense

places, where people can shelter in

place, work remotely, and have all of

their food and other needs delivered

to them, and poor dense places,

which push people out onto the

streets, into stores and onto crowded

transit with one another.” These

complexities have been addressed in

the shared housing literature through

the “voluntary vs. involuntary” lens,

namely, delineating shared housing

behavior and outcomes based on the

constraints under which individuals

either choose or are forced to live in

shared housing.

Public health situations like the

COVID-19 national emergency,

ongoing at the time of this paper's

publication, can present residents

sharing housing with some

challenges, which are similar to

challenges residents may face around

other household expectations, like

chores, rules about visitors, and

other household activities, but are

compounded due to the severity of

the risks to health and livelihood.

Shared housing residents who have

come together through shared beliefs,

like in many co-ops and other types

of intentional communities, may be

more willing to develop and comply

with new household policies during

emergency scenarios. For example,

certain medium-sized co-ops in

Oakland, California; San Francisco,

California; Berkeley, California;

Boulder, Colorado; Providence,

Rhode Island; New York City, New

York; and Austin, Texas have all

published household policies that

they developed and co-signed under

COVID-19, many categorizing their

allowable activities into different

phases of the pandemic. The Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention

released safety information on

living in shared housing during the

COVID-19 pandemic, including

limiting or avoiding nonessential

visitors and stocking COVID-19

prevention supplies, such as soaps,

sanitizers, tissues, trash bins, and

if possible, cloth face coverings.

Maximizing health and happiness

during crisis situations involves

a level of trust between shared

housing residents that there will

be compliance with agreed-upon

household expectations. It may also

involve meeting certain housing

quality standards to ensure that any

resident who becomes affected by the

virus can self-isolate without harming

their housemates.

Pandemics such as COVID-19 are

once-in-a-lifetime events, and, while

governments should always invest in

emergency preparedness, pandemics

may present characteristics of

a “black swan” event (that is,

rare and unpredictable events

despite post-hoc rationalizations

for predictability), requiring ad

hoc policies to respond to crisis

scenarios. How residents and owners

of shared housing make contingency

plans to protect their health and

safety during public health crises

may play a lesser role in the overall

health of residents in their long-term

relationship with shared housing.

Sources: Florida, Richard. 2020. The

Geography of Coronavirus. CityLab.

https://www.citylab.com/equity/2020/04/

coronavirus-spread-map-city-urban-

density-suburbs-rural-data/609394/

Tina, Cynthia. 2020. COVID-19

Resources. Center for Intentional

Community. https://www.ic.org/

covid-19-resources/

Center for Disease Control. 2019. Living

in Shared Housing. https://www.cdc.gov/

coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/

shared-housing/index.html

Social relationships are a major benefit

of shared housing and can mitigate the

substantial negative health effects that often

accompany social isolation and loneliness.

7

Prevalence of Shared Housing

in the United States

One can measure the prevalence of

shared housing in the United States using

multiple approaches. Here, we look at

data captured by major federal surveys.

We examine the following variables

captured by the American Housing

Survey (AHS), American Community

Survey (ACS), and Current Population

Survey (CPS):

v

the number of unoccupied

bedrooms in housing units, the number

of families per household, the types of

families in households, the relationship

v

Data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and American Community Survey (ACS) provide information on household composition in the United States. The

ACS is an ongoing household survey that samples approximately 3.5 million randomly selected households per year. The survey captures detailed social, demographic,

economic, and housing data of the U.S. population. Surveys are conducted by mail through a questionnaire delivered to an address, via internet, through in-person

interviews by U.S. Census Bureau field representatives, and by telephone.

The

CPS is a household survey conducted monthly, using a probability sample of roughly 60,000 households. Households are interviewed by Census field

representatives once a month for 4 consecutive months, and then interviewed again over the same 4 months, 1 year later. Households from each state and the District of

Columbia are included in the survey. The survey provides information on the labor market and household composition and demographics. Data from the Annual Social

and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the CPS provides further detailed social and economic information on individuals in a household and household composition.

ASEC data is used by the U.S. Census Bureau to measure poverty.

The

American Housing Survey provides information on the housing stock, vacancies, housing costs, and the condition of housing units, among other detailed information

on housing. The survey is conducted biennially in odd-numbered years. In 2017, the most recently completed survey, the survey sampled 114,860 housing units.

of household members to their head

of household, and multigenerational

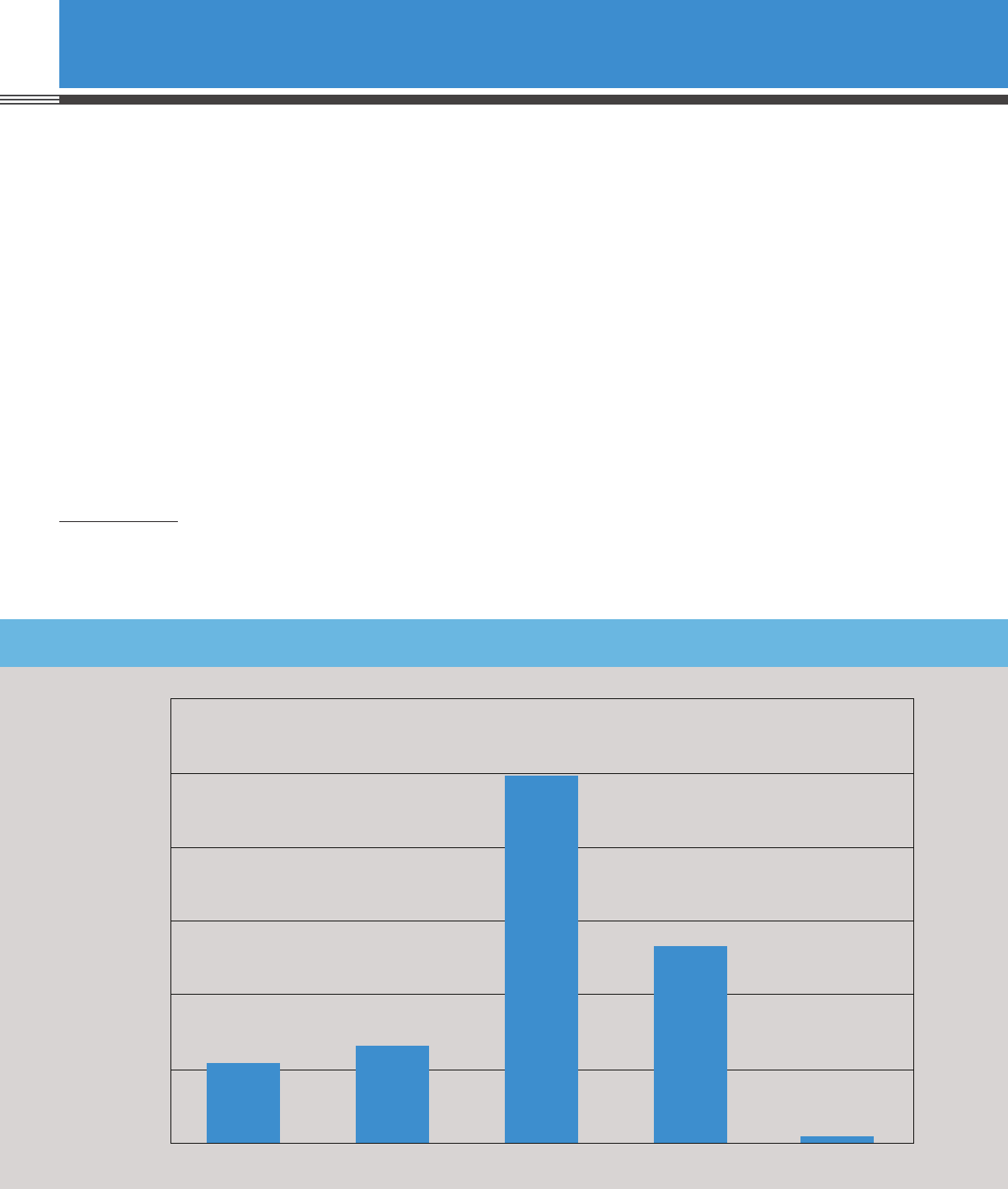

households. See Figure 2 for a summary

of the analysis of these variables.

Data from the AHS shows that 76

percent of occupied housing units

have more than one bedroom per

person. Formal measures from CPS

and ACS indicate that shared housing

represents a less common but growing

housing arrangement for American

households, whereas AHS data shows

the capacity for shared housing in

the U.S. housing stock. Data from the

CPS and ACS show that, although the

prevalence of shared housing varies

substantially depending on the age of

the household head, roughly 7 percent

of households contain more than one

family; 9 percent of households include

subfamilies or secondary individuals

(a steadily growing 2-percentage-point

increase in share from 2000 to 2019);

4 percent of ACS respondents are

not related to the head of household;

and 20 percent of Americans live in

multigenerational households with more

than two adult generations (a steadily

growing 8-percentage-point increase in

Figure 2: Metrics on the Prevalence of Shared Housing in the United States

Shared Housing Metric Data Source Time Period Findings

Unoccupied bedrooms American Housing

Survey

2019 Of all occupied housing units:

• 26% have 2+ bedrooms per person

• 50% have 1-2 bedrooms per person

• 24% have <1 bedroom per person

Finder.com analysis

of U.S. Census data

2017 • There are 33.6 million spare rooms in the United States

• There are ~9.4% more bedrooms than people

Number of families

per household

Current Population

Survey

2020 • 94% of households contain one family

• 4% of households contain two families

• 2% of households contain three or more families

Types of families in

households

Current Population

Survey

2020 • 73% of households are primary families

• 18% of households are nonfamily householders

• 9% of households are subfamilies and

secondary individuals

Relationship between

household members

American

Community Survey

2019 • 3% of people identified as nonrelatives in relation to the

head of household

Multigenerational

households

American

Community Survey

2019 • 35% of households are one-generation households

• 53% of households are two-generation households

• 9% of households are three-generation households

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

8

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

share from 1980 to 2016). The variance

among these indicators paint a different

picture depending on how shared

housing is defined, demonstrating the

importance of additional research to

capture changes in Americans’ living

arrangements. Overall, these measures

illustrate some degree of increase in the

rate and prevalence of shared housing

and suggest the capacity for further

expansion of such housing arrangements.

vi

Undercrowding occurs when there are too few occupants in a housing unit. In context, this percentage is a national measurement of all housing units, and there is

variation in crowdedness in different housing markets across the United States, where some markets have greater and lesser degrees of crowding and undercrowding in

housing units. In some areas of the United States, there is an acute problem of overcrowding in housing units, notably in Indian Country/Tribal Lands.

Unoccupied Bedrooms

Data on unoccupied bedrooms represent

one measure used to examine the

capacity for shared housing in the

United States. This measure indicates

the capacity for homeowners to engage

in home sharing, based on the presence

of extra unoccupied bedrooms in a

house. The AHS finds that 26 percent of

occupied housing units have two or more

bedrooms per person, whereas 50 percent

have between one and two bedrooms per

person. Having more than one bedroom

per person may make sense if residents

have rooms they use as office spaces

or guest bedrooms; however, couples

typically share a bedroom, which would

reduce the average number of bedrooms

per person. The fact that just 24 percent

of occupied units have less than one

bedroom per person suggests that

undercrowding is much more prevalent

than overcrowding in the United States.

vi

See Figure 3.

According to a 2017 analysis by finder.

com, U.S. Census data show that there

are approximately 33.6 million spare

Figure 3. Number of Bedrooms Per Person in Occupied Housing Units in the United States

Source: American Housing Survey, 2017 National – Rooms, Size, and Amenities – All Occupied Units

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Share of occupied housing units

0.66 or less 0.67 to 0.99 1.00 to 1.99 2 or more No bedrooms

11%

13%

50%

26%

1%

The prevalence of shared housing in the

United States likely ranges somewhere

between 3 to 20 percent of households,

depending on the dataset and definition used.

9

rooms in the United States. This finding

is based on aggregate estimates of

roughly 357 million bedrooms for 324

million people, or 9.4 percent more

bedrooms than people.

39

This aggregate

estimate is likely an overestimate of the

availability for home sharing because

it appears to include bedrooms in

vacant housing for sale or rent and

does not account for households that

are using their additional rooms for

essential purposes. Separately, a 2017

analysis of local real estate markets

by Trulia examined boomer-headed

households in the 100 largest U.S.

housing markets, and they found

at least 3.6 million unoccupied

rooms, not counting offices or guest

rooms, in these markets.

40

Either way,

each of these estimates shows the

United States’ potential capacity to

absorb demand for home sharing.

Number of Families Per Household

The Current Population Survey (CPS)

counts the number of families living

in a household, defining family as

anyone related by blood, adoption, or

marriage, whereas unrelated individuals

are counted as a separate family. This

measurement considers households with

multiple generations as one family (for

example, a married couple with children

living together with grandparents would

be counted as one family). According to

CPS data, in 2020, roughly 94 percent

of households contained one family;

4 percent of households contained

two families; and 2 percent contained

three or more families. By counting the

number of families in a household, we

can generally see that roughly 6 percent

of households included more than one

family, and that percentage includes

unrelated adults. These figures have

been relatively stable over the past two

decades. Since 2001, the percentage of

one-family households increased by 0.9

percent at an annual rate of 0.045; the

percentage of two-family households

decreased by 1.06 percent at an annual

rate of 0.063; and the percentage of three

or more family households increased by

0.15 percent at an annual rate of 0.0075.

This CPS data shows that among all

households, sharing housing is relatively

uncommon despite the possible capacity

to do so.

In 2020, among households headed

by those aged 65 and older, nearly 98

percent were one-family households and

2 percent were two-family households,

including unrelated individuals. CPS

data further suggests that relatively few

senior-aged households contained more

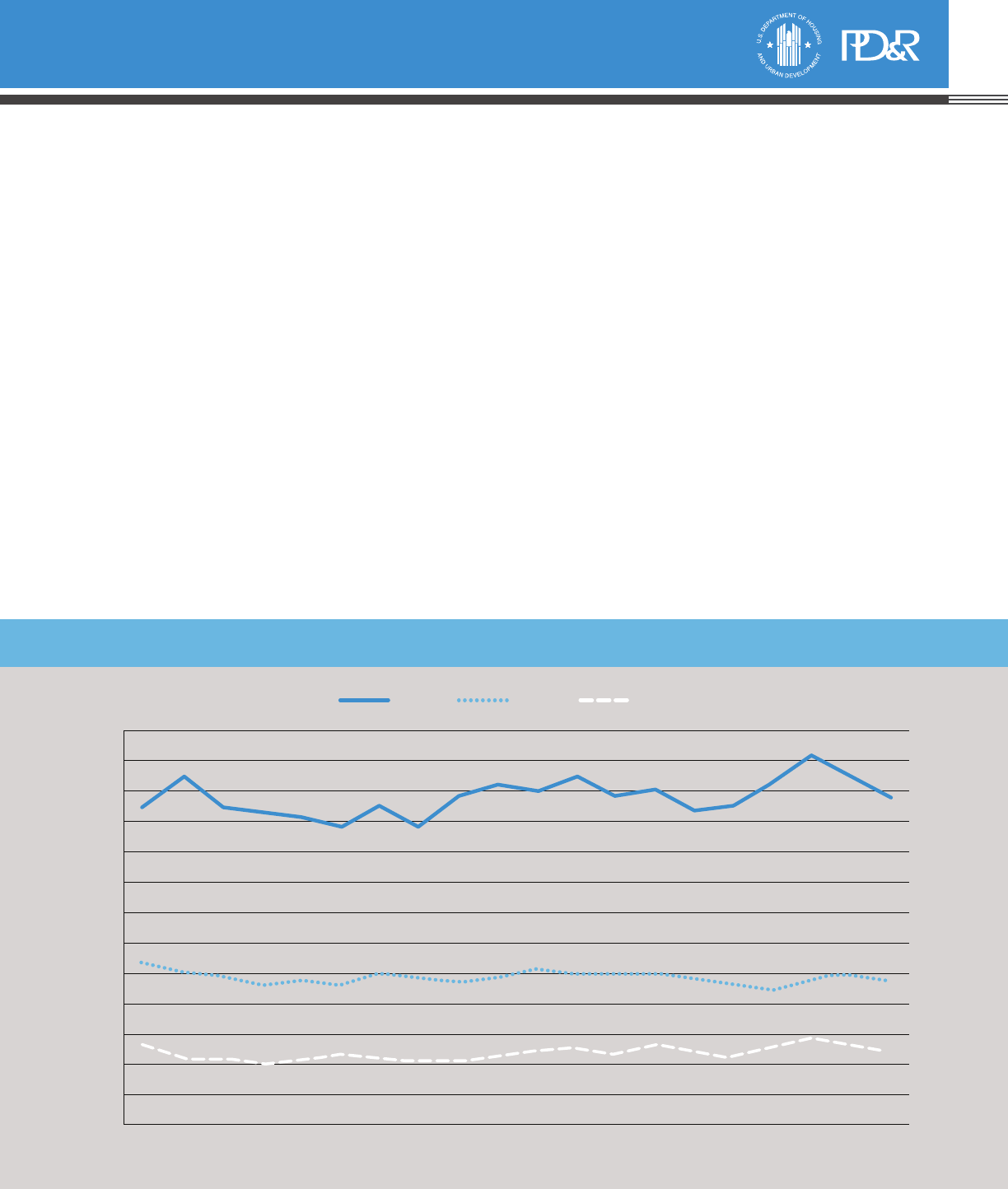

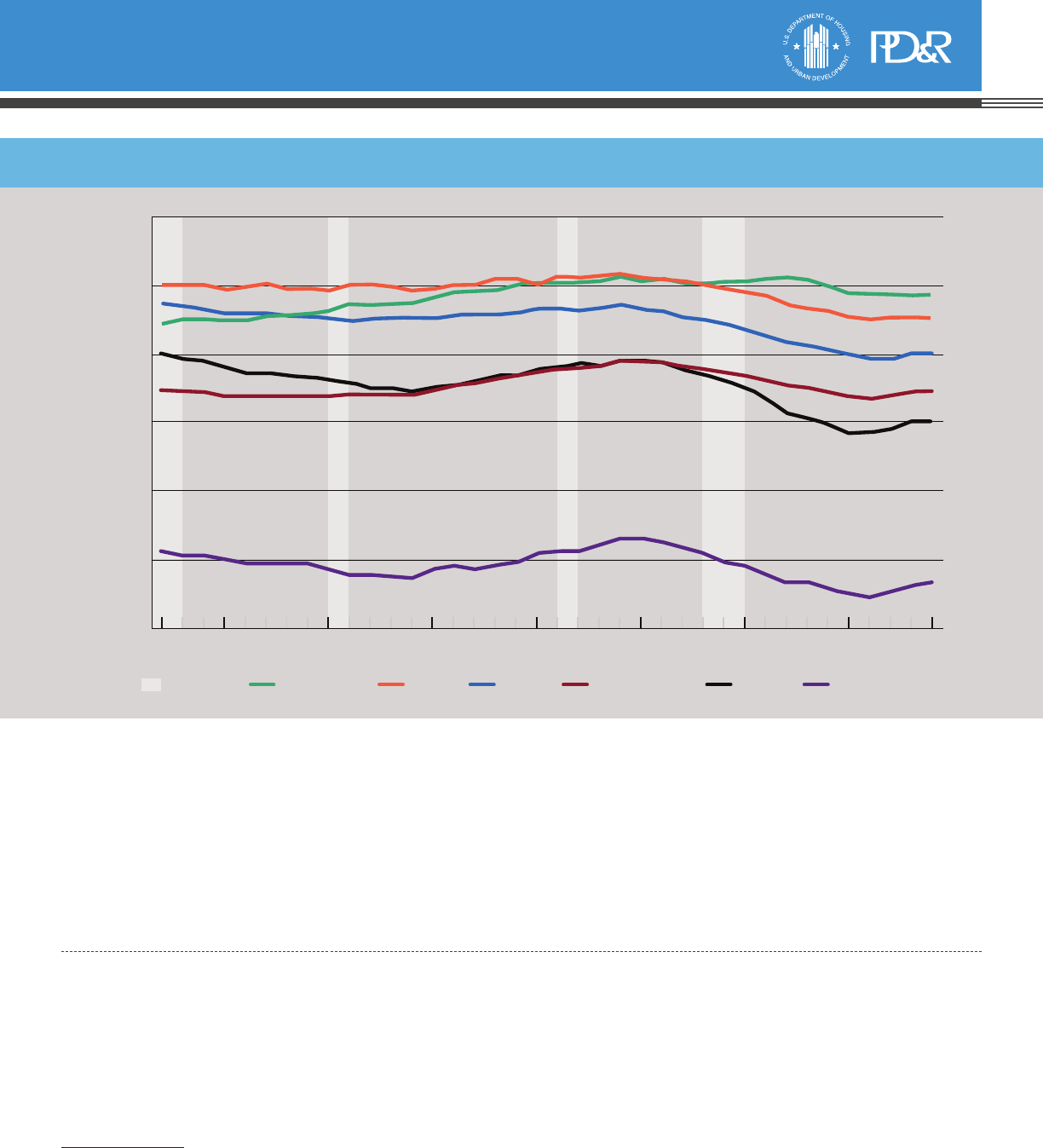

Figure 4. Share of Households That Contain More Than One Family by Age Cohort of Householder

13

12

11

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

2011

10.5

10.9

4.7

2.4

5.4

2.6

25-34 35-64 65-99

Source: Current Population Survey, NFAMS variable

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

10

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

than one family, indicating that there are

few senior-aged households participating

in shared housing relative to households

in other age cohorts. See Figure 4 for a

breakdown by age cohort.

Types of Families in Households

The CPS also counts the types of

families living in a household, defining

five different family types: primary

families, nonfamily householders, related

subfamilies, unrelated subfamilies, and

secondary individuals. By this count,

in 2020 primary families—defined as

a group of two or more people related

by birth, marriage, or adoption that

is living together—make up nearly

three-fourths of all households.

vii

vii

According to CPS data, in 2020, roughly 73.21 percent of households were occupied by primary families; 17.8 percent of households were occupied by nonfamily

householders; 8.98 percent of households were occupied by subfamilies or secondary individuals. Over the past two decades, these percentages have been relatively stable.

Since 2001, the percentage of primary families decreased by 2.54 during the period at an annual rate of 0.127; the percentage of nonfamily households increased by 1.15

during the period at an annual rate of 0.0575; and the percentage of subfamily and secondary individuals increased by 1.39 during the period at an annual rate of 0.0695.

Nonfamily householders, defined as a

person maintaining a household while

living alone or with nonrelatives, made

up about 18 percent of households.

Subfamilies (subfamilies do not maintain

the household but live in someone

else’s home) and secondary individuals

(unrelated roomers, boarders, resident

employees) account for about 9 percent

of the remaining household types.

These data show that most households

in the United States are occupied by

primary families. Unrelated subfamilies

and secondary individuals, who can be

considered as sharing housing, make

up about 6 percent of all households.

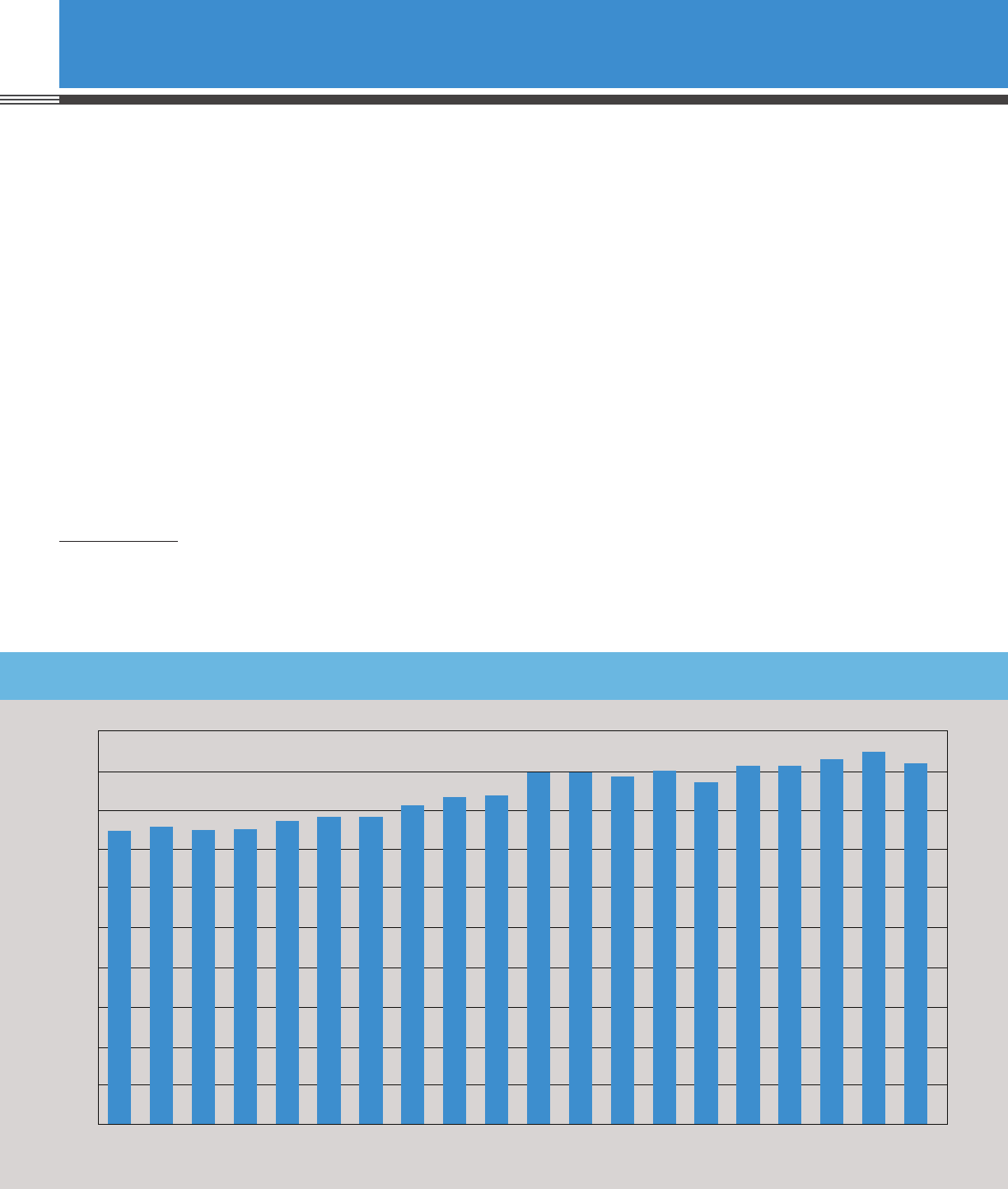

See Figure 5 for the percentage of

households with subfamilies or

secondary individuals.

Related subfamilies are defined as a

married couple with or without children,

or a single parent with one or more

children under 18. An example of a

related subfamily is a married couple

sharing the home of the husband’s or

wife’s parents. In 2020, about 3 percent

of households in the United States were

related subfamilies. Unrelated subfamilies

are defined as a married couple with

or without children, or a single parent

with one or more children under

18, and can include guests, partners,

roommates, or resident employees

and their spouses and children. In

2020, 0.18 percent of households

in the United States were unrelated

subfamilies. A secondary individual is

defined as a roomer, boarder, or resident

Figure 5. Percentage of Households with Subfamily or Secondary Individual

Source: Current Population Survey

10

8

6

4

2

0

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

2011

7.5

9.2

11

employee with no relatives in the

household; this includes group quarter

members not living with a relative. In

2020, about 6 percent of households

in the United States were secondary

individuals. During the same period

about 9 percent of households included

a subfamily or secondary individual.

Relationship Between Household

Member and Household Head

The ACS captures the relationship of each

individual to the household head. Among

the 13 different types of relationships

captured are “other non-relatives”—

defined as people paying or working for

accommodations. ACS data show that

in 2019, 2.95 percent of respondents

identified as other nonrelatives in relation

to the head of household. Since 2001,

that percentage has increased by 1.73 at

an annual rate of 0.091.

A 2018 article from Harvard University’s

Joint Center for Housing Studies

examined the prevalence of shared

housing among people aged 65 and

older. Using 2016 ACS data, the author

found that shared housing arrangements

among people aged 65 and older are

relatively small in scope but increasing.

In 2016, roughly 879,000 people aged

65 and older lived with another unrelated

person, whereas 12.8 million lived alone

and another 21.7 million lived with a

spouse or partner

41

:

Though the number and share of

older adults living with unrelated

roommates is small, both grew

dramatically between 2006 and

2016. Over that time, when the

older population grew from 38 to 50

viii

Pew Research shows that Asian and Hispanic populations are more likely to live in multigenerational households than White households, and these populations are

growing more rapidly than White populations in the United States. Indeed, in 2016, the shares of households that are multigenerational are higher among Asians (29

percent), Hispanics (27 percent), and Blacks (26 percent) than among White households (16 percent).

million, an increase of 33 percent,

the segment of the older population

sharing their homes grew from 1.3 to

1.8 percent, and the number of older

adults in these arrangements grew by

88 percent (from about 470,000 to

nearly 988,000).

Separately, the Census released a report

on shared households in 2012 titled,

“Poverty and Shared Households by

State: 2011,” which found that in

2007, 17.6 percent of households were

shared households, and in 2010, that

number increased to 19.4 percent.

42

Also, the report found that in 2007,

16 percent of adults were additional

adults in a shared household, and that

in 2010, that number increased to 17.3

percent.

43

The report further found that

most (80.8 percent) additional adults

in shared households were relatives of

the householder, whereas 19.2 percent

were not relatives. Adult children of the

householder were the most common

additional adult at 47.1 percent,

whereas 8.1 percent were siblings, 9.6

percent were parents, and 16 percent

were other relatives.

44

Multigenerational Households

Finally, ACS data on multigenerational

households in the United States is

examined. Multigenerational housing

is a common living arrangement in the

United States; it is a household that

consists of at least two adult generations.

Most commonly, this arrangement

occurs when grandparents live with

their adult children and grandchildren.

Multigenerational housing can provide

a range of benefits for participating

individuals. In addition to reduced

housing costs for participants,

such arrangements can allow for

grandparents to “age in place” in a

familiar environment. Grandparents

can also help parents supervise their

children, reducing the costs for daycare

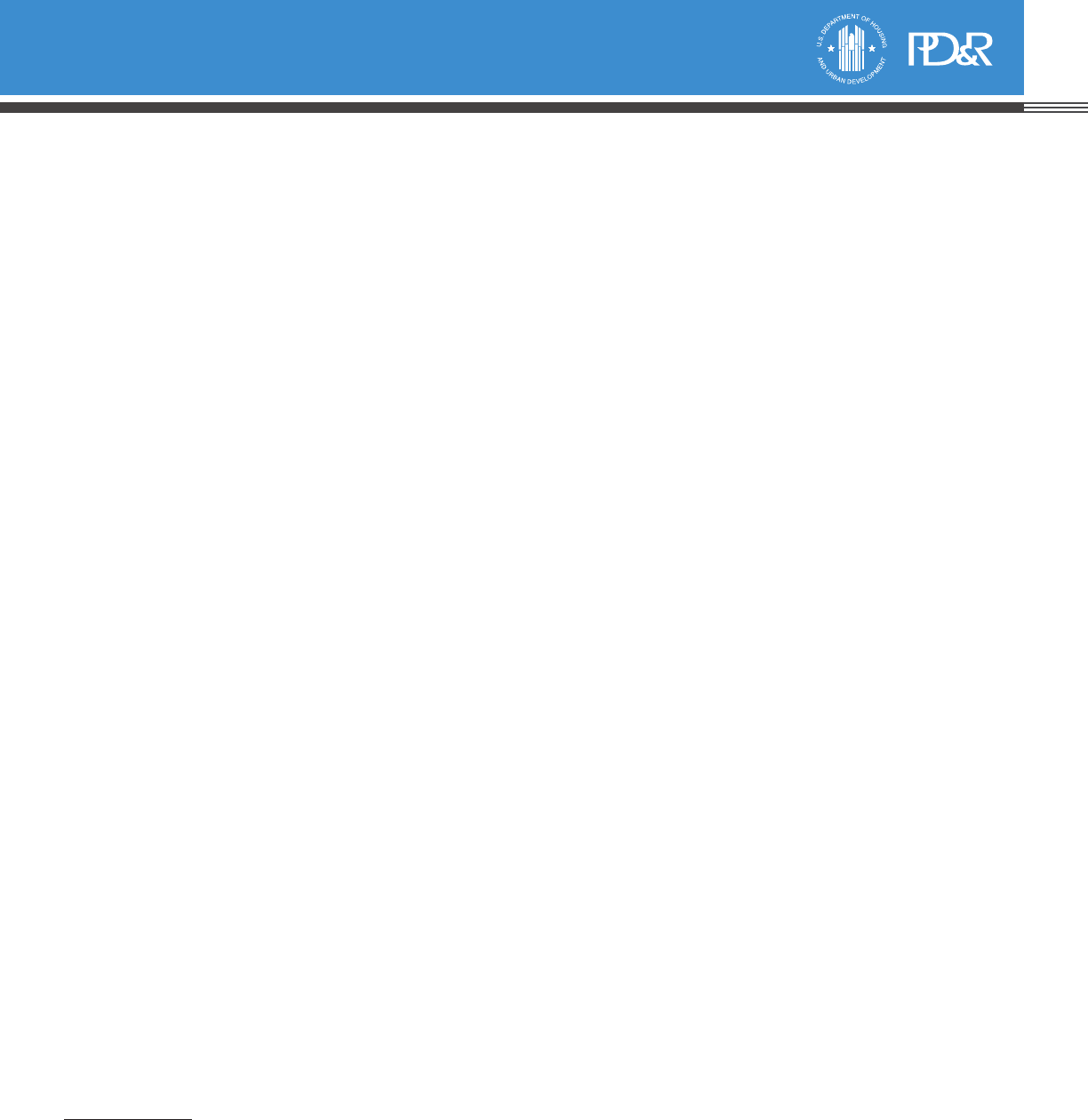

and other childcare. See Figure 6 for

the percentage of Americans living in

multigenerational households.

45

In 2019, among all reporting adult

households, about 35 percent were

one-generation households, 54 percent

were two-generation households, and 9

percent were three-generation or more

households. Since 2001, the percentage

of one-generation households increased

by 0.63 at an annual rate of 0.033; two-

generation households decreased by 5.07

percent at an annual rate of 0.267; and

three or more generational households

increased by 1.97 percent at an annual rate

of 0.104. The share of households with

three or more generations has increased in

recent years.

46

Analyzing ACS data, Pew Research

found that in 2018, 20 percent of the

population lived in multigenerational

housing, a 5-percentage-point increase

from 2000.

47

In their analysis, they

define multigenerational housing

as housing that includes “two or

more adult generations, or including

grandparents and grandchildren

younger than 25.” The increase in

multigenerational households can be

explained partially by the increase of

racial and ethnic diversity in the United

States and different cultural preferences.

viii

Overall, based on varying methods

of counting members of households,

shared housing is a small but growing

way of living in the United States.

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

12

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

Shared Housing Models in the United States

We now provide an overview of two of

the primary models for shared housing:

home sharing and co-living. Home

sharing and co-living are operated

by both nonprofit and for-profit

organizations in the United States, and

they tend to range in the length of their

leases and in their affordability. Several

existing home sharing and co-living

organizations were interviewed to obtain

qualitative information about their

operations for this section.

Home Sharing

Home sharing organizations are

intermediary organizations that match

shared housing seekers to shared housing

providers. Home sharing is available to all

age cohorts, from young adults starting

new jobs in big cities to retirees looking

for extra income to help pay mortgages

and property taxes. Most home sharing

participants who share their homes are

older adults, however.

48

Home sharing organizations have

been operating in the United States for

decades, with some current organizations

having programs that began in the 1970s

or 1980s. Home sharing organizations

in the United States have adapted their

models of matching home seekers

and home providers over time. The

National Shared Housing Resource

Center (NSHRC) operates as a network

for home sharing organizations in the

United States, promoting best practices

among home sharing organizations

and providing resources and learning

opportunities for practitioners.

49

The

housing model for home sharing

organizations, including best practices, is

explained on the next page.

Typically, home seekers and providers

contact a home sharing organization

seeking a home sharing match.

Organizations often list their criteria for

participating on their websites and allow

participants to apply online through a

website template, or via e-mail or telephone.

For participants providing housing, the

organization typically visits and inspects the

unit prior to placing a participant seeking

housing.

50

After participants apply, they

are screened through background checks

Figure 6. Increasing Share of Americans Living in Multigenerational Households

Sources: Pew Research Center, 2018; Decennial census and ACS data

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

1980 1990 2000 2009 2016

12%

14%

15%

17%

20%

13

Home Sharing Model

Vetting Process

Thorough vetting and interview

processes help ensure a successful

match is made between participants.

Home sharing organizations interview

home providers to understand the

types of arrangements they seek.

The information gathered includes

preferences on desired rent payment;

the type of services preferred, if any;

and compatibility information, such as

sharing with an individual or a family,

work schedule, and so on. The vetting

process—including applications,

background checks, and participant

interviews—helps maximize the

likelihood of compatibility among

participants. Through a trial

period, follow up, and mediation,

the organizations provide further

assistance to ensure successful matches

for participants.

Although shared housing

organizations use similar models

for matchmaking, they can differ in

a variety of ways, including length

of leasing, rent payment, services

provided, and client base.

Length of Leasing

Home sharing organizations differ in

the length of leasing arrangements

for their matches—whether short-

term (such as month-to-month

leasing arrangements) or long-term

(a year or more). For example, in San

Mateo, California, Human Investment

Project (HIP) Housing participants

seek and enter into month-to-month

arrangements. On average, home

sharing arrangements last 2 to 3 years

in duration, with some arrangements

lasting 10 years or longer. Other

organizations facilitate month-to-

month arrangements, which on average

last 1.5 years. Participants move on for

many reasons, including changes in

lifestyle or living situations.

Client Base

Although most shared housing

organizations are available to anyone

seeking housing, the client base of

some organizations differ. For example,

Impact Justice in Alameda County,

California, began a pilot program

called The Homecoming Project,

which matches formerly incarcerated

people with participating homeowners

providing short-term housing limited

to 6 months. The Homecoming Project

aims to reduce the recidivism rate

among the formerly incarcerated by

providing short-term, stable housing to

help increase their chances to re-enter

society. The Homecoming Project

subsidizes homeowners and, like other

shared housing organizations, screens

participants, facilitates the matching

process, and offers follow up support.

Some shared housing organizations

adapt their shared housing programs

to meet demand for their services.

For example, HomeShare Vermont

began their home sharing program by

matching senior-aged home seekers

to senior-aged home providers. They

found that the program gained interest

in other age cohorts, however, and

they then began an intergenerational

approach to home sharing that did not

restrict participants by age or income;

this approach opened the program to

more participants.

Payment (Exchange of Rent

and Services)

When interviewing prospective

home providers, shared housing

organizations ask what type of rent

payment or services the home provider

is seeking, whether rent payment

only, services only, or a combination

of rent and services. Likewise,

prospective home seekers are asked

about their preferences and their

ability to provide rent payment and

services. Rent can range extensively

depending on the location of the

shared housing arrangement. Services

can include housework, yardwork,

pet care, fellowship and conversation,

or running errands to the grocer or

pharmacy, and so on. Services are often

specified in terms of number of hours

per week or month. Services typically

do not include personal care.

Sources: Phone interviews with HomeShare

Vermont (conducted on June 25, 2019) and

HIP Housing (conducted on June 25, 2019)

and are interviewed by the organization,

after which the organization arranges for

the home seeker and home provider to

meet.

51

,

52

,

53

Finally, after a trial period, the

participants enter into a more formal leasing

agreement.

54

Once participants are settled,

organizations follow up with participants to

ensure satisfaction and mediate in the case

of conflict between participants.

55

Co-Living

Co-living organizations are a type

of shared housing organization

that facilitate co-living—a housing

arrangement in which a tenant pays

rent for a private bedroom but shares

common living areas such as kitchens,

bathrooms, and laundry facilities with

other tenants. Co-living is convenient

for people just arriving to a new city

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

14

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

or for people looking for an affordable

housing option in a high-demand area.

Part of the co-living appeal is found in

the convenience and all-inclusive pricing

for renters, at the expense of reduced

privacy and smaller living spaces. Co-

living organizations typically bundle

their rent, utilities, and Wi-Fi into an all-

inclusive rate for renters. Many co-living

providers offer fully furnished dwellings,

including furnished bedrooms, but

provisions vary across organizations.

Co-living buildings can range from large

multi-unit buildings to renovated single-

family homes with multiple bedrooms.

Co-living buildings are built or renovated

to maximize density by adding extra

bedrooms, which can reduce the amount

of square footage in a bedroom or

common area, such as a living room,

compared to traditional units. For new

developments, co-living organizations

advise developers on how to best

optimize properties for co-living, while

for renovations, co-living organizations

advise property owners how to optimize

current space for maximum density.

Co-living buildings can be found in

Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York

City, San Francisco, and Washington,

D.C., among other major U.S. cities.

The increasing market capitalization of

co-living shows that it is a fast-growing

real estate sector, with opportunities

to significantly impact urban housing

markets in the United States.

ix

ix

Of the total investment in co-living specific to the United States through 2018, 55 percent was made in 2018. Moreover, combined capital investment fundraising

in U.S. and international co-living housing markets has grown more than 200 percent annually since 2015. In 2019 alone, about $3 billion in funding was secured

for co-living development in the U.S. and international markets. Jones Lang LaSalle. 2019. Why investors are signing up for coliving. June 17, 2019. https://www.

us.jll.com/en/trends-and-insights/investor/why-investors-are-signing-up-for-coliving.

The increasing market

capitalization of co-

living shows that

it is a fast-growing

real estate sector,

with opportunities to

significantly impact

urban housing markets

in the United States.

Co-living organizations often have

user-friendly websites and mobile apps,

which serve as one-stop shops for

renters and prospective renters. Housing

seekers can apply for membership and

set up appointments for viewing units

(some co-living organizations offer

virtual tours), whereas current renters

can pay rent and request services and

maintenance. It makes sense that co-

living is technology-driven, given

its origin during the digital age and

its typical target market, which are

technology-savvy younger generations.

56

Variance in Co-Living Models

Co-living companies are typically

organized into three different models:

the operator model, the full stack

(developer-owner-operator) model,

and the single-family conversion

model.

57

Co-living organizations operate

differently throughout the United States

depending on local regulations, the

types of co-living models in operation,

and their target demographics. For

example, Common is a co-living

organization operating in eight major

cities (as of 2020), with plans to expand

to more U.S. cities.

58

,

59

Common operates

similar to hotels, in that it offers rooms

and common areas with high-end

furniture, weekly cleaning, household

supplies (such as paper towels, toilet

paper, and cleaning supplies), and

monthly community-building events.

60

Common includes the costs for these

amenities, including utilities and Wi-Fi,

in the cost of rent, so that the price is

all-inclusive for renters. Rent for these

co-living arrangements is at or near the

market rate for similar group house

listings, but because co-living comes

with furnished rooms and all-inclusive

pricing, collecting payment for utilities

or other amenities is no hassle. These

higher-end co-living arrangements

are typically marketed toward people

earning incomes of $60,000 to $80,000,

or who are college-educated young

professionals moving to a new city

and are seeking convenient housing.

15

Source: Cushman & Wakefield, https://cw-gbl-gws-prod.azureedge.net/-/media/cw/americas/united-states/insights/research-report-pdfs/2019/

coliving-report_may2019.pdf (p. 39)

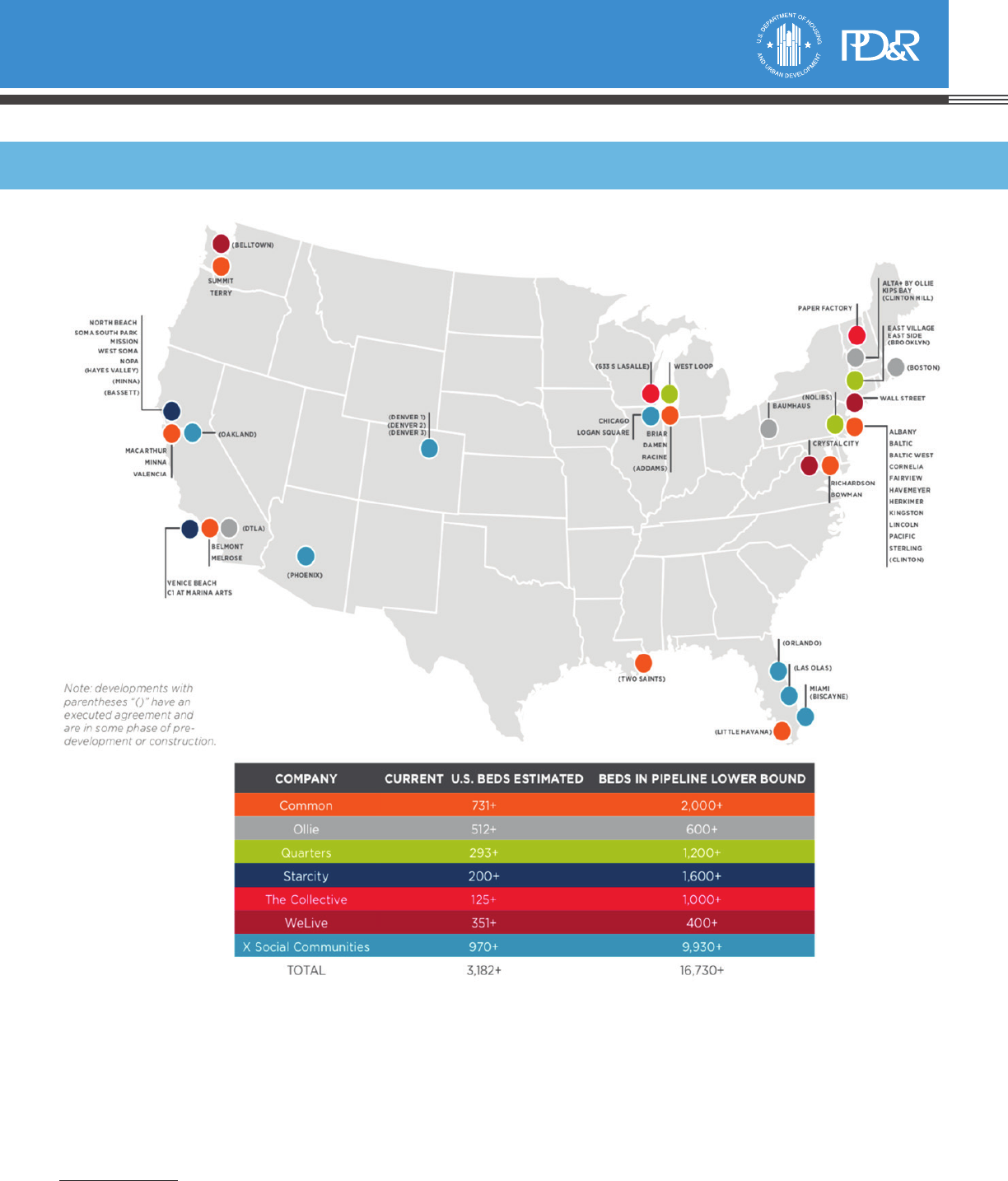

Figure 7. Major U.S. Co-Living Developments

x

Figure 7.

x

x

Note this figure does not include every coliving organization in the United States. For example, PadSplit, based in Atlanta, has a current estimate of approximately

1,000 units, with an additional 2,000 units in the pipeline.

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

16

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

Co-Living Model

Leasing

Co-living organizations vary in

their leasing arrangements. Some

organizations own and manage the

unit or building and lease to tenants in

traditional leasing agreements. Other

organizations facilitate short-term

rentals for property owners looking to

rent out a property. Similar to home

sharing organizations, co-living leasing

arrangements can vary in duration from

a single night to a full year or longer,

depending on the co-living provider and

the type of arrangement. The co-living

provider is typically the leaseholder, so

tenants sub-lease the rental space. For

Common, the typical lease length is

around 12 months, but shorter leasing

options ranging from 3 to 9 months

are also offered. For PadSplit, members

typically stay about 7.5 months.

Vetting Process

Co-living organizations vet prospective

members to ensure a safe living

environment for all tenants. To become

a co-living member, individuals typically

must apply through online applications.

Some organizations charge one-time

application fees. Once applications are

received, co-living organizations usually

run credit and criminal background

checks. Once background checks

are cleared, applicants are offered

membership and can begin applying to

rent vacant units.

Rent Payments

Depending on the co-living organization

and the leasing arrangement, rent

payments can be due monthly or weekly.

Co-living members are only responsible

for the rent owed for their room, not the

rent for the entire house or unit. Rent

amounts can vary as well, with some

organizations charging the market rate

and others charging more affordable

rental rates.

Sources: Phone interviews with Common and

PadSplit conducted on January 24, 2020

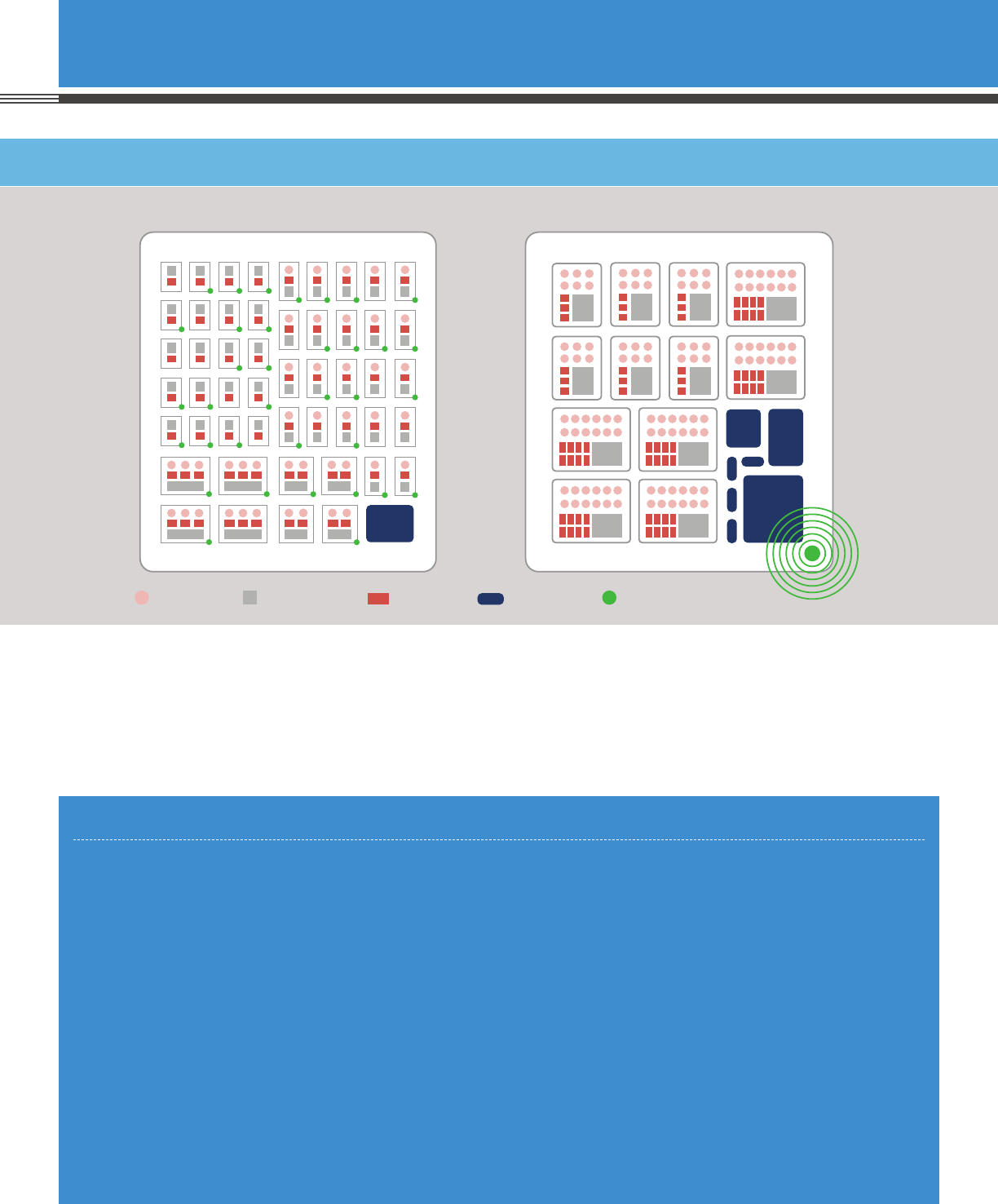

Figure 8. Common’s Co-Living Model

Traditional Rental Co-Living

Bedroom Living Space Bathroom Amenities Services and Technology

Source: Common, https://www.common.com/blog/2019/10/common-announced-as-winner-of-sharenyc-hpd

Other co-living organizations offer fewer

amenities, while still including fully

furnished buildings and all-inclusive

pricing for renters. These are generally

marketed toward temporary workers,

and those earning lower incomes, who

are seeking affordable housing.

61

For

example, PadSplit, based in Atlanta,

offers co-living housing at affordable

prices, where the average income of their

members is $21,000.

62

17

Challenges Faced by Shared

Housing Organizations

Shared housing organizations face a

variety of challenges in their operations.

Some include the availability of housing

stock, financing availability, and local

regulations that restrict shared housing.

Housing Availability

Demand for shared housing and

services from shared housing

organizations (both home sharing and

co-living organizations) exceeds the

availability.

63

In other words, there

are many more people seeking shared

housing arrangements than there are

formal shared housing arrangements

available. Finding available home

providers is a challenge for shared

housing organizations.

64

,

65

The older

that homeowners become, the less

likely they are to share their homes.

In some instances, by the time senior

homeowners come around to the idea of

shared housing, they need professional

care beyond that which can be provided

through shared housing arrangements.

There are many more

people seeking shared

housing arrangements

than there are formal

shared housing

arrangements available.

Due to the lack of available home

providers, and by nature of the

arrangement, shared housing

organizations cannot guarantee

placement for home-seeking participants.

Depending on the area, three to five

times as many shared-housing seekers

can exist as available providers.

66

When

there is a waitlist, shared housing

xi

Some appraisers will not appraise the value of the home without a comparable housing unit. For single-family homes, appraisers generally determine the value of a

home using a comparison approach, where they determine the value of a property by comparing it to other properties within the area that are similar in size and room

count. They determine value by looking at home sales in the area over the previous three months, and adjust that value based off of location, upgrades, and other

variables. Assessing the value of a home can be more difficult without a comparable housing unit, which is the case with co-living residences in single-family homes.

Source: phone interview with PadSplit conducted on June 30, 2020.

organizations generally inform new

home-seeking participants of other

housing resources in the area.

67

Funding Availability

Funding for shared housing varies

depending on the business model of the

shared housing organization. Many shared

housing organizations, especially home

sharing organizations, operate as nonprofit

organizations in the United States. As

such, identifying funding sources can be

a challenge, particularly when operating

resource-intensive programs such as

home sharing, where staff are needed for

each phase of shared housing. Funding

sources for nonprofit providers vary by

organization, but include fundraising,

donations, grants, state funds, and funds

raised through partnership with other

nonprofit organizations with similar

housing objectives.

68

,

69

,

70

Securing funding—particularly financing

for new loans—can also be a challenge

among for-profit co-living organizations.

Many lenders are hesitant because co-

living is a relatively new housing model,

and fewer underwriting guidelines have

been established.

71

Developers may be

reluctant to engage an investment project

involving the co-living model if there is

ultimately the risk they would have to

rebuild and renovate the building if the

project is unsuccessful.

72

For renovations,

it can be difficult for owners to secure a

traditional, lower-rate construction loan

because co-living is a new housing model

and lenders are not ready to underwrite

the risk. Even if the owner can go

through with renovations, the owner may

have difficulty having the value of the

property appraised without a comparable

unit in the area.

xi

Despite these challenges with a nascent

model, capital for co-living real estate

development can be raised by pointing

to the potential returns. Indeed, many

for-profit co-living models can charge

higher rents and net higher profits than

traditional types of multifamily apartment

buildings.

73

These gains can motivate

private investors who are willing to take

on more risk to invest in developments

built for co-living models.

Complying with Local Regulations

Depending on the jurisdiction, shared

housing can be subject to the same or

different land-use and zoning regulations

as other housing types. Navigating local

regulations can be a challenge, especially

when organizations attempt to scale

operations across cities and jurisdictions.

These special housing types can be

difficult for regulators to assess within

local jurisdictions.

Residential zoning ordinances can

restrict the ability to share housing,

thereby restricting the availability of

affordable housing in an area.

74

Zoning

ordinances determine how land is

used and what types of buildings and

features are permitted or prohibited on

apportioned land. Zoning is the act of

partitioning land in a municipality for

different purposes, such as for residence

or commercial use.

75

Most land is not

zoned federally in the United States;

state governments have the authority to

enforce zoning regulations, and states

typically delegate that authority to local

governments and municipalities.

Land-use regulations are traditionally

put in place for reasons of public health

and safety, and they also typically provide

benefits to existing homeowners through

restrictions on land uses and building

allowances. Zoning regulations that set

density restrictions, height restrictions,

parking requirements, minimum lot sizes,

and open space requirements, among

other rules, can discourage development

Insights into Housing and Community Development Policy

18

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development | Office of Policy Development and Research

in areas where builders could otherwise

maximize the number of units on land

parcels and their occupancy to increase

profitability. Of particular relevance,

shared housing organizations can

operate in multifamily residential zones,

but with the exception of a few localities,

in the United States, the majority of land

zoned for residential uses is zoned for

single-family homes. This section focuses

on several local land-use regulations

that especially affect shared housing

opportunities: occupancy standards,

density regulations, and rules around

accessory dwelling units (ADUs). A

brief overview of strategies to reduce

regulatory barriers to shared housing is

also provided.

Occupancy Standards

Housing regulations that impact

shared housing organizations include

occupancy standards, which limit the

maximum number of people who may

reside in a dwelling unit. For example,

the “U plus 2” occupancy ordinance

in Fort Collins, Colorado, restricts the

number of unrelated people who may

live in a house to three people.

xii

,

76

The

city of Fort Collins has recently been

considering amending their occupancy

limit law to allow more people per

dwelling unit, so long as they adhere

to additional safety and community

standards.

77

The current ordinance is

unfavorable among students at Colorado

xii

The “U plus 2” occupancy limit law, enacted in the 1960s, set the maximum permissible occupancy of a dwelling unit at one family and not more than one other

person; or two adults and their dependents and not more than one additional person; or up to three unrelated persons in a dwelling unit located in an apartment

complex containing units which were approved by the city.

State University in Fort Collins because

it reduces the availability of affordable

housing by restricting the number of

people who may live in a dwelling

unit. By contrast, in Washington, D.C.,

occupancy limit laws allow up to six

unrelated people to live in a single-

family home.

78

Restrictive occupancy

laws have a direct impact on the ability

for residents to engage in shared

housing models.

In Washington,

D.C., occupancy

limit laws allow up

to six unrelated

people to live in a