U.S. Department of Justice

Oce of Justice Programs

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Bulletin

February 2022, NCJ 301735

Stalking Victimization, 2019

Rachel E. Morgan, Ph.D., and Jennifer L. Truman, Ph.D., BJS Statisticians

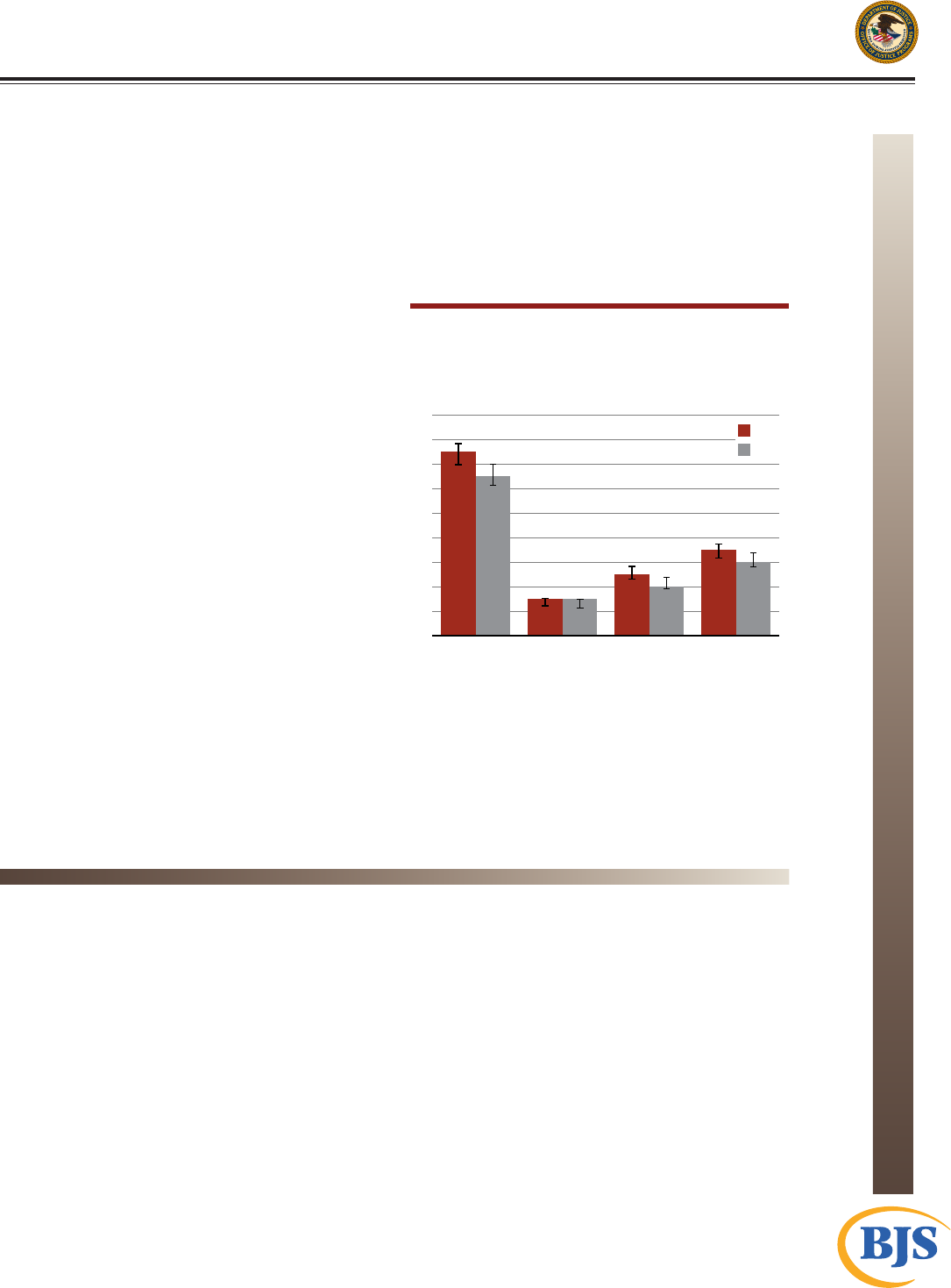

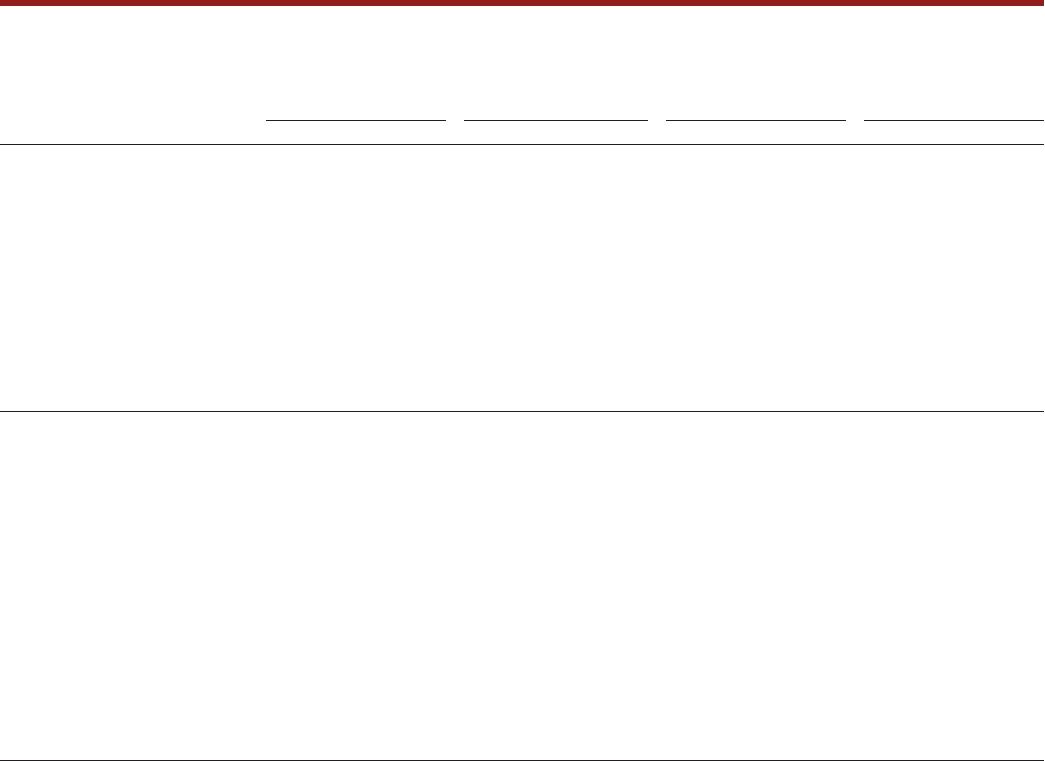

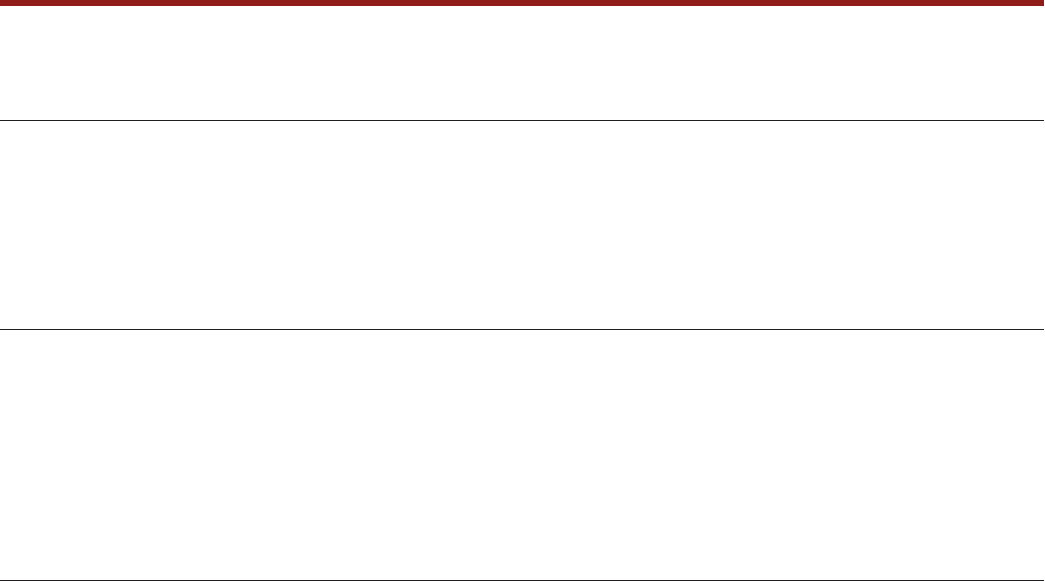

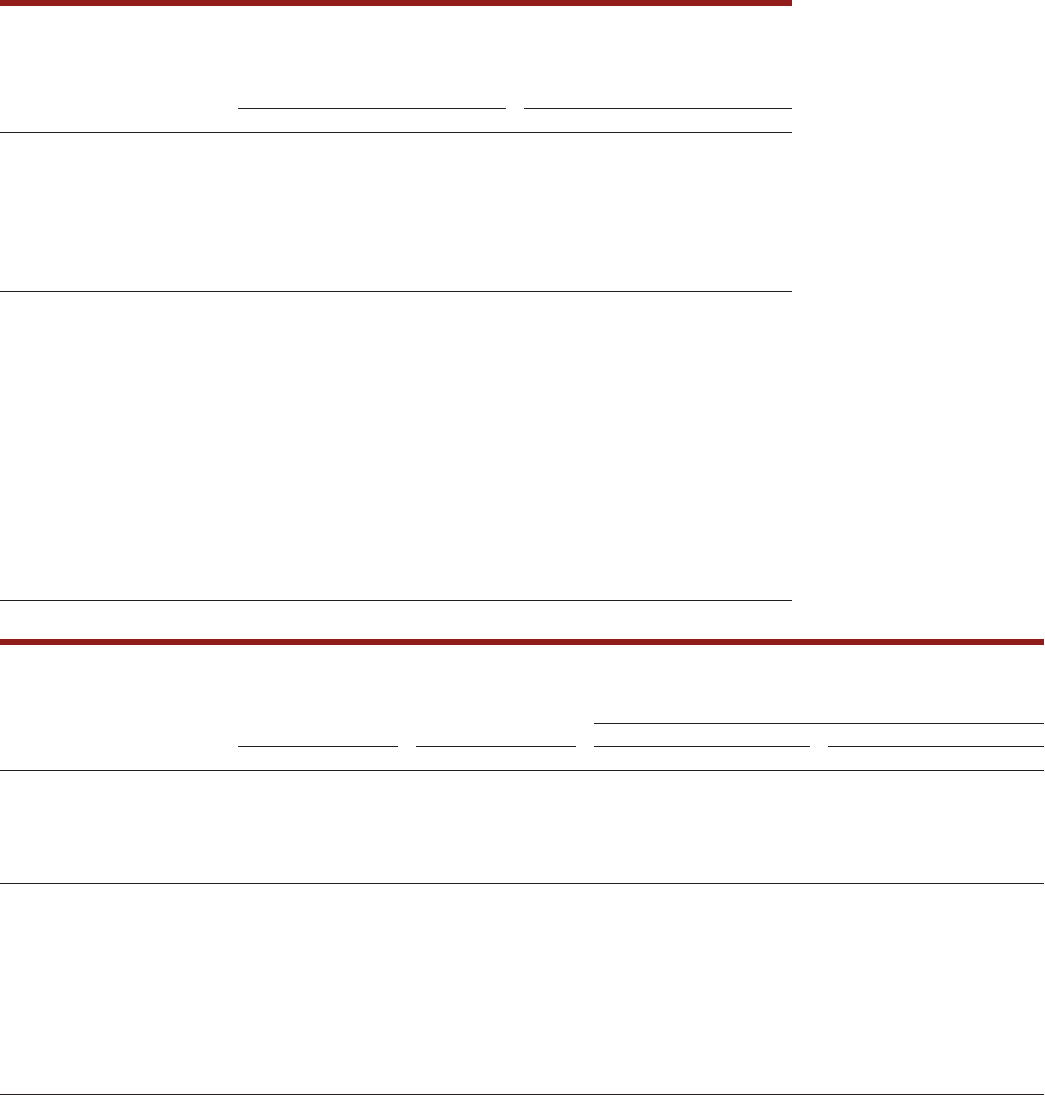

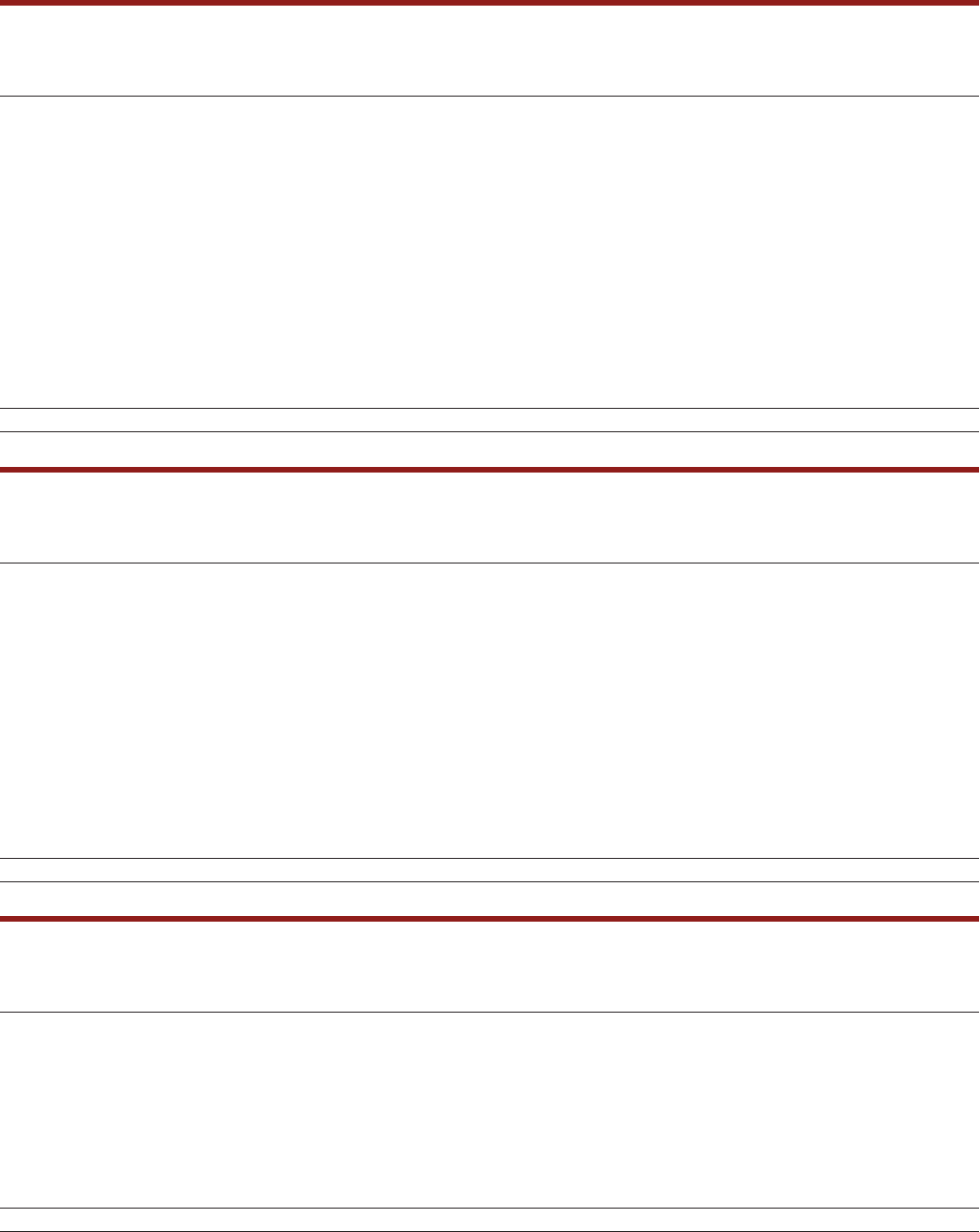

I

n 2019, an estimated 1.3% (3.4 million) of all

U.S. residents age 16 or older were victims

of stalking (gure 1). is was a statistically

signicant decrease from 2016 (1.5%) that was

largely driven by a decline in stalking with

technology only, from 1.3 million victims in 2016

to 1.1 million in 2019. (See appendix table 1.) In

comparison, the number of victims of traditional

stalking only or both traditional and technology

stalking did not change signicantly during this

period. Stalking includes repeated unwanted

contacts or behaviors that caused the victim

to experience fear or substantial emotional

distress or would cause a reasonable person to

experience fear or substantial emotional distress.

Findings are based on the 2019 Supplemental

Victimization Survey (SVS) to the National

Crime Victimization Survey. From July 2019

to December 2019, the SVS asked persons

age 16 or older about their experiences with

stalking during the 12 months preceding the

interview. is report details the demographic

characteristics of victims who were stalked

Figure 1

Prevalence of stalking, by type of stalking, 2016

and 2019

Percent of all persons age 16 or older

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

Both traditional

stalking and stalking

with technology

Stalking with

technology only

Traditional

stalking only

Total

2019*

2016

†

†

Note: Estimates include 95% condence intervals. See appendix

table 1 for denitions. See appendix table 2 for estimates,

standard errors, and stalking denitions.

*Comparison year.

†Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 95%

condence level.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization

Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2016 and 2019.

HIGHLIGHTS

About 1.3% (3.4 million) of all persons age 16 or

older were victims of stalking in 2019.

The percentage of persons who experienced

stalking declined from 1.5% in 2016 to 1.3%

in 2019.

Less than a third (29%) of all stalking victims

reported the victimization to police in 2019.

In 2019, females (1.8%) were stalked more than

twice as often as males (0.8%).

In 2019, an estimated 67% of victims of both

traditional stalking and stalking with technology

were fearful of being killed or physically harmed.

Most (67%) stalking victims knew their stalker.

Victims of both types of stalking in 2019 were

more likely to be stalked by an intimate partner

(35%) than victims of only traditional stalking

(11%) or only stalking with technology (18%).

Victims of both stalking types were more than

twice as likely to have applied for a restraining,

protection, or no-contact order as victims of

traditional or technology stalking only.

In 2019, about 16% of all stalking victims sought

victim services and 74% of the victims who

sought services received them.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 2

during a 12-month period. It also describes the

characteristics of stalking victimization, including the

victim-oender relationship, self-protective actions

taken by the victim, patterns of reporting to police, and

whether the victim contacted a victim service provider

aer the victimization.

Two-thirds of victims of stalking with technology

received unwanted phone calls, voice messages, or

text messages in 2019

e most frequently reported traditional stalking

behaviors in 2019 included the oender following and

watching the victim (58%) or showing up at, riding

by, or driving by places where the oender had no

business being (49%) (table 1). Nearly 42% of victims

of traditional stalking said the oender harassed their

friends or family for information on their whereabouts.

Almost a third (31%) of traditional stalking victims said

the oender waited for them at home, school, or another

place. More than a h (22%) said the oender le or

sent unwanted items. In 2019, less than a h (17%) of

victims said that the oender snuck into their home,

car, or another place to let them know the oender had

been there.

Stalking with technology victims most commonly

received unwanted phone calls, voice messages, or text

messages (66%) in 2019, followed by unwanted emails or

messages via the Internet (55%). About 32% of victims of

this type of stalking said their activities were monitored

using social media. Twenty-nine percent experienced the

oender posting or threatening to post inappropriate,

unwanted, or personal information about them on

the Internet.

Twenty-two percent of stalking with technology victims

said the oender spied on them or monitored their

activities using technologies such as listening devices,

cameras, or computer or cellphone monitoring soware.

About 14% were tracked with an electronic tracking

device or application.

Table 1

Persons age 16 or older who were victims of stalking, by type of stalking behavior, 2019

Type of stalking behavior

Number

of stalking

victims

a

Percent

of stalking

victims

Percent of

all persons

b

Total 3,419,710 100% 1.3%

Any traditional stalking 2,300,830 67.3% 0.9%

Followed or watched 1,344,250 58.4 0.5

Showed up at/rode by/drove by places 1,122,720 48.8 0.4

Harassed/repeatedly asked friends/family for information 955,470 41.5 0.4

Waited at home/work/school/any other place 718,100 31.2 0.3

Left/sent unwanted items 507,800 22.1 0.2

Sneaked into home/car/any other place 391,880 17.0 0.2

Any stalking with technology 2,738,470 80.1% 1.1%

Made unwanted phone calls/left voice messages/sent text messages 1,802,160 65.8 0.7

Sent unwanted emails/messages using the Internet or social media 1,493,980 54.6 0.6

Monitored activities using social media 873,850 31.9 0.3

Posted/threatened to post inappropriate/unwanted/personal information

c

802,040 29.3 0.3

Spied on or monitored activities using technology 610,180 22.3 0.2

Tracked whereabouts with an electronic device/application 394,000 14.4 0.2

Note: Details may not sum to totals because victims could experience more than one type of stalking behavior. The total population age 16 or older was

260,731,490 in 2019. See appendix table 3 for standard errors. See Methodology for question wording for the types of stalking behaviors.

a

Number of persons age 16 or older who experienced stalking victimization in the past year.

b

Percentage of persons age 16 or older who experienced stalking victimization in the past year.

c

Includes posting private photographs, videos, or rumors.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 3

Measuring stalking victimization

To be classied as a victim of stalking in the

Supplemental Victimization Survey (SVS), the respondent

must have experienced a repeated course of conduct (i.e.,

experienced the same behavior or contact more than

once or experienced two or more dierent behaviors one

time) that either—

caused them substantial emotional distress or to fear

for their safety or the safety of someone they know

(actual fear)

would cause a reasonable person to fear for their safety

or the safety of someone they know.

Reasonable fear includes victimizations where the victim

reported that they experienced either—

damage, attempted damage, or destruction

of property

threatened, attempted, or completed attacks on the

victim, someone close to them, or a pet.

The SVS measured 12 types of stalking behaviors,

incorporating both traditional stalking and stalking

with technology.

Traditional stalking includes the following

unwanted behaviors:

following and watching

sneaking into a place

waiting at a place

showing up at a place

leaving or sending unwanted items

harassing friends or family about the

victim’s whereabouts.

Stalking with technology includes the following

unwanted behaviors:

making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages,

or sending text messages

spying using technology

tracking the victim’s whereabouts with an electronic

tracking device or application

posting or threatening to post unwanted information

on the Internet

sending unwanted emails or messages using

the Internet

monitoring activities using social media.

See Methodology for the SVS questions used to measure

actual fear, substantial emotional distress, reasonable

fear, and the types of unwanted behaviors that

victims experienced.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 4

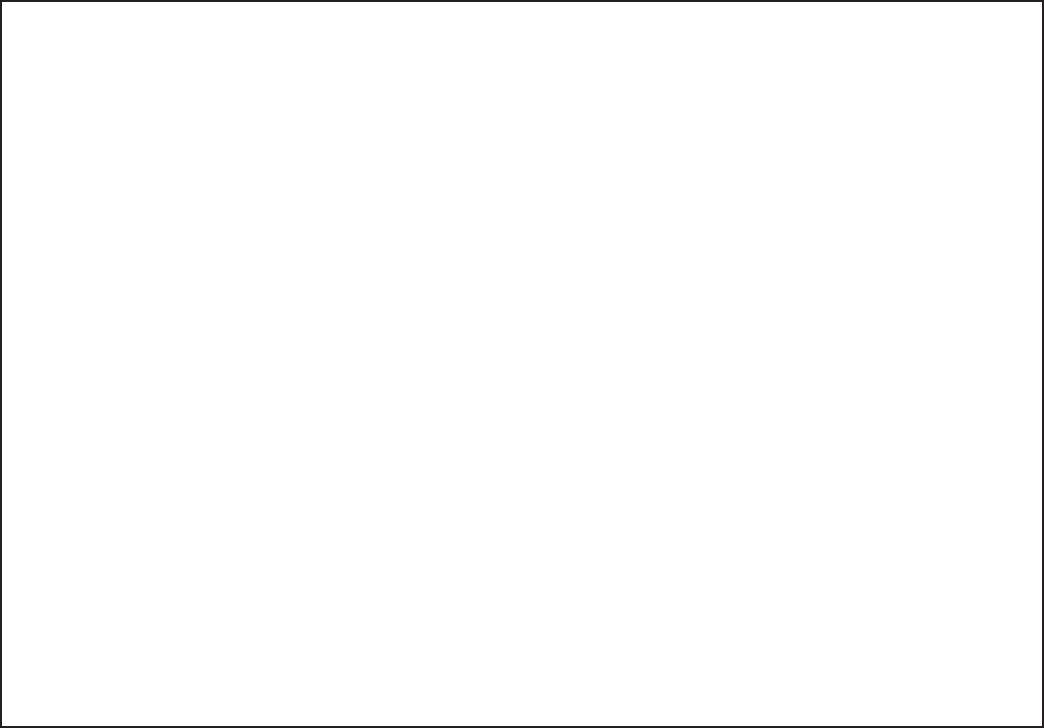

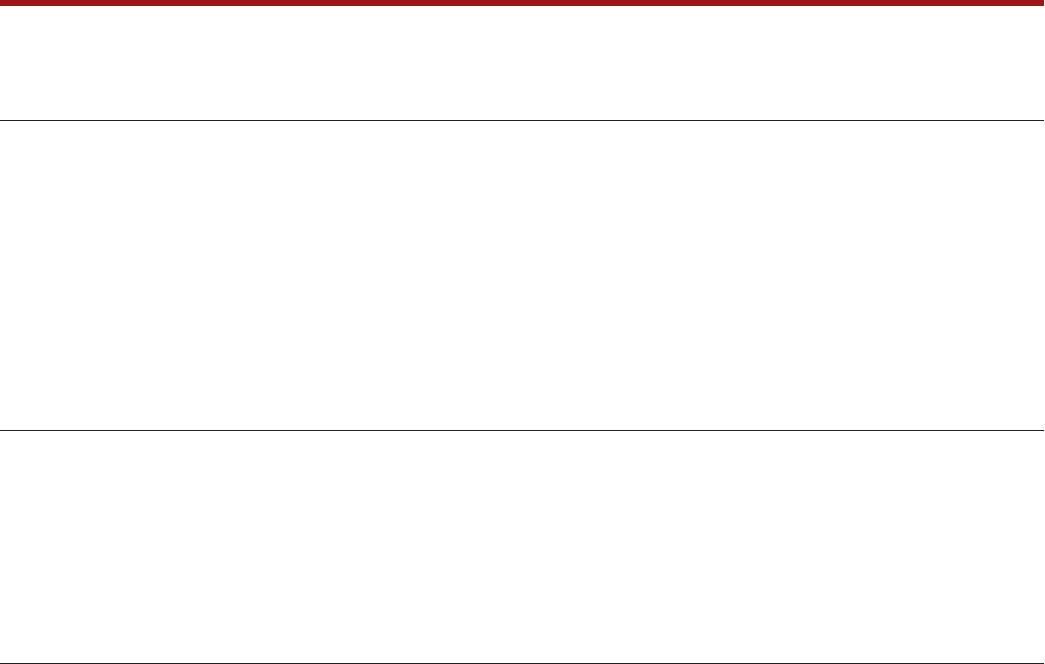

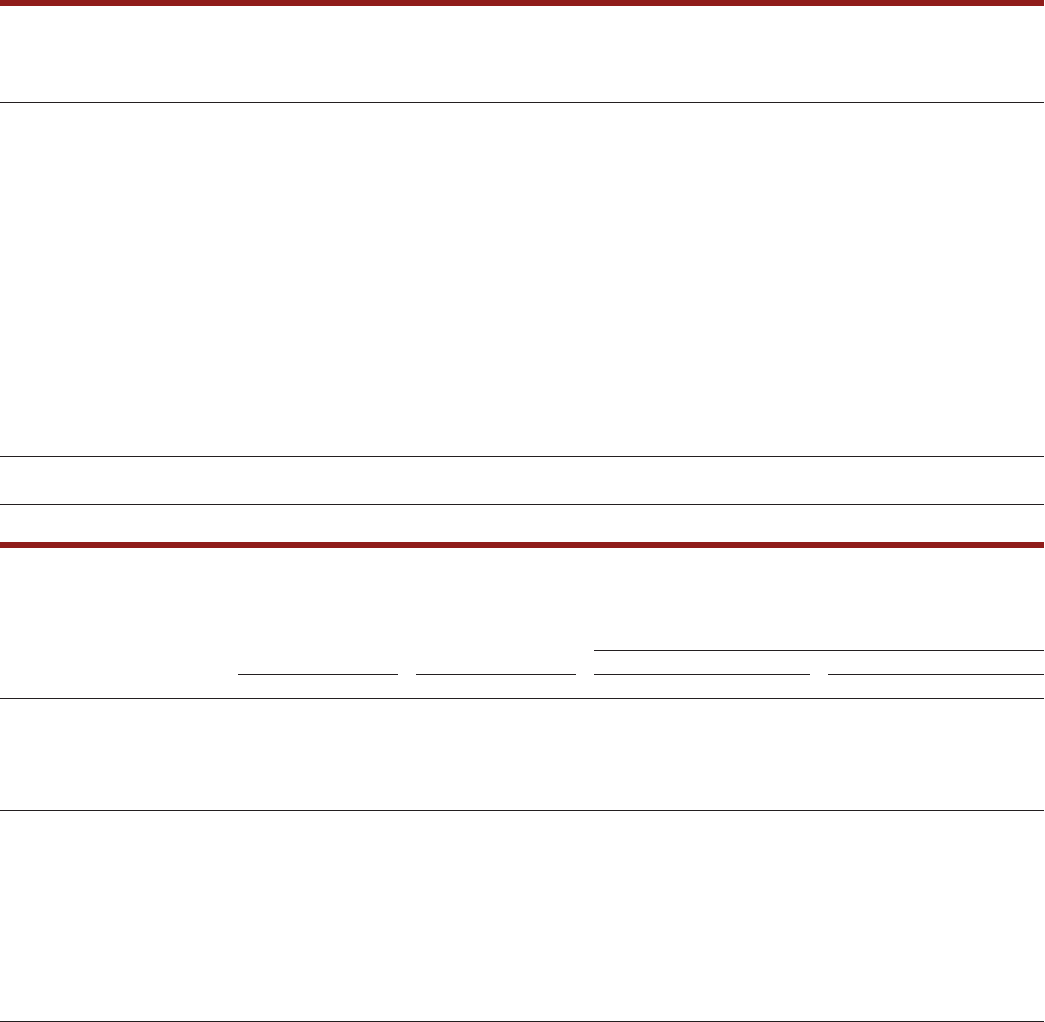

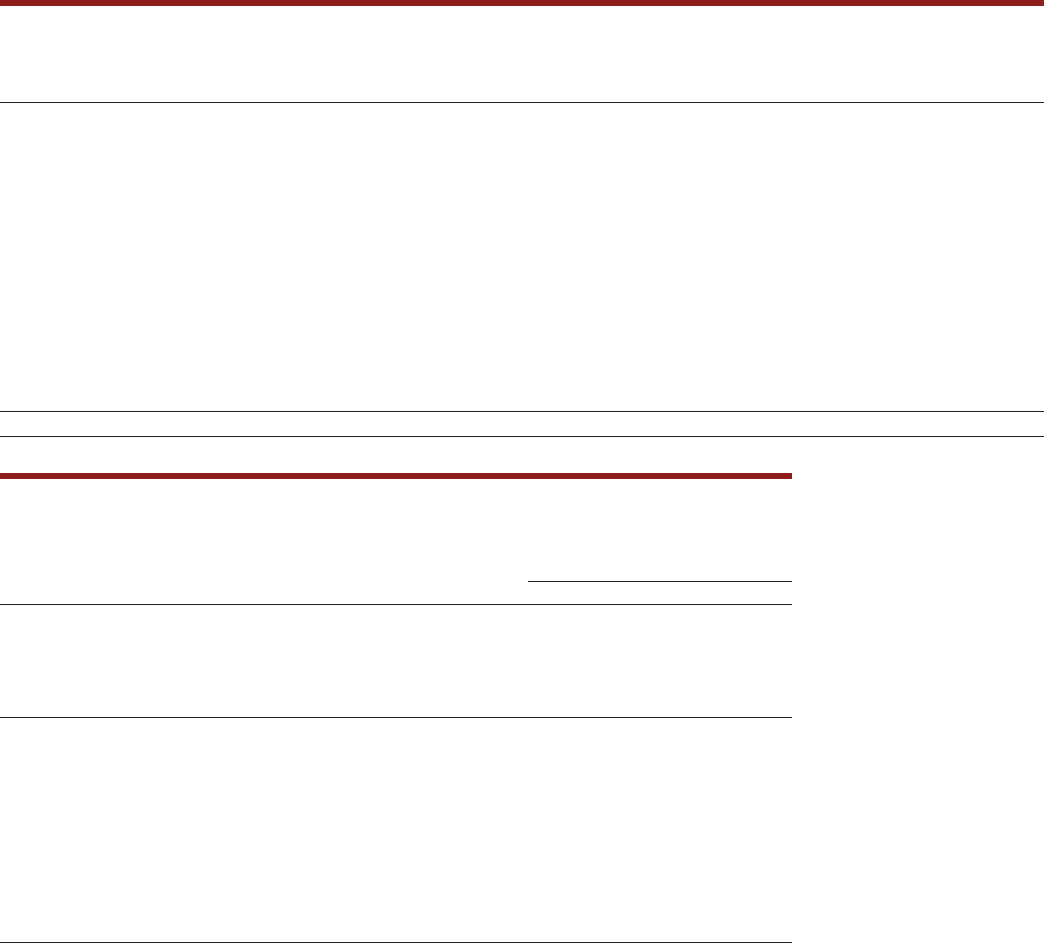

Less than a third of all stalking victims reported the

victimization to police in 2019

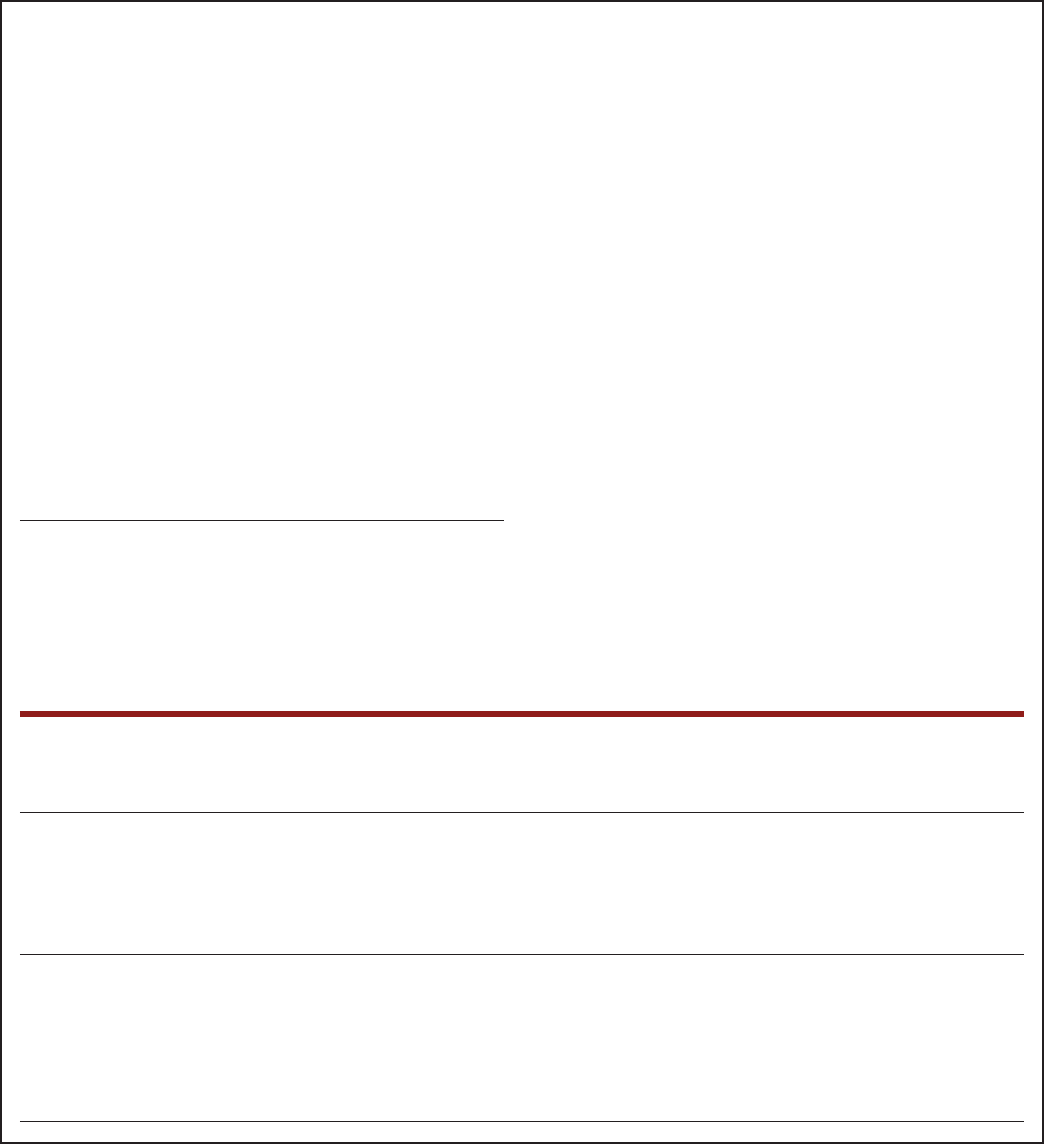

In 2019, 29% of all stalking victims reported the

stalking victimization to police (gure 2). Victims who

experienced both traditional stalking and stalking with

technology reported to police more oen (32%) than

victims who experienced stalking with technology only

(23%) (statistical testing performed and not shown).

From 2016 to 2019, reporting to police declined among

traditional stalking victims (from 39% to 30%) but

increased among stalking with technology victims

(from 16% to 23%). During this period, there was no

statistically signicant change in police reporting among

all stalking victims or victims who experienced both

types of stalking.

Crime victims chose not to report their victimization

to police for a variety of reasons. One of the most

common reasons was feeling that the victimization was

not important enough to report to police. In 2019, this

reason was cited by about 40% of all stalking victims,

traditional stalking victims, stalking with technology

victims, and victims who experienced both traditional

stalking and stalking with technology (table 2).

From 2016 to 2019, increasing shares of all stalking

victims and traditional stalking victims who did not

report to police said they did not think the police could

do anything to help. e portion of all stalking victims

citing this reason grew from 27% to 33% during this

period, while the percentage of traditional stalking

victims citing this reason rose from 21% to 39%.

Figure 2

Percent of stalking victims who reported to police, by

type of stalking, 2016 and 2019

Percent of stalking victims

0

10

20

30

40

50

Both traditional

stalking and stalking

with technology

c

Stalking with

technology only

b

Traditional

stalking only

a

Total

‡

†

2019*

2016

Note: Estimates include 95% condence intervals. See appendix table 4 for

estimates and standard errors.

*Comparison year.

†Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 95% condence level.

‡Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 90% condence level.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking

into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted

items; or harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted

phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying

using technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking

device or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted

information on the Internet; sending emails or messages using the

Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey,

Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2016 and 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 5

Table 2

Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking, reporting to police, and reason for not reporting, 2016 and 2019

Total stalking Traditional stalking only

a

Stalking with

technology only

b

Both traditional

stalking and stalking

with technology

c

2016 2019* 2016 2019* 2016 2019* 2016 2019*

Total 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100%

Reported to police 28.1% 28.7% 38.9% ‡ 29.6% 15.9% † 22.7% 32.9% 32.3%

Not reported to police 70.2% 70.9% 59.9% † 70.3% 83.5% † 77.1% 64.4% 66.9%

Reason not reported

d

Not important enough to report 40.6 41.6 47.7 43.8 42.0 43.0 36.8 39.5

Dealt with it another way 37.8 40.3 38.4 34.7 36.0 39.1 39.2 43.8

Police couldn’t do anything 26.5 † 32.9 20.6 † 39.0 30.9 33.0 24.5 30.3

Police wouldn’t help 15.5 ‡ 19.4 19.9 24.3 12.9 15.1 16.3 20.8

Other/unknown reason

e

13.2 15.5 16.3 12.3 7.4 6.7 17.7 ‡ 24.0

Feared oender 6.3 7.8 7.2 11.3 3.8 5.0 8.5 8.5

Number of victims 3,788,800 3,419,710 703,250 681,240 1,316,360 1,118,890 1,769,190 1,619,580

Note: Details may not sum to totals due to missing data and because victims could select more than one reason for not reporting to police. Data on

reporting to police were missing for 1.7% of all stalking victimizations in 2016 and 0.4% in 2019. See appendix table 5 for standard errors.

*Comparison year.

†Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 95% condence level.

‡Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 90% condence level.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted items; or

harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying using

technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet;

sending emails or messages using the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

d

Includes victims who did not report the stalking to police. Details do not sum to totals because victims could select more than one reason for not

reporting to police.

e

Includes victims who said they did not trust police, felt ashamed or embarrassed, or did not want to get the oender in trouble with the law; the oender

was an ex-spouse or ex-partner; they obtained a protection order instead; the victim or oender moved away; it was for their children’s well-being; the

unwanted contacts or behaviors stopped; some other reason; or the reason was unknown.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2016 and 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 6

Cyberstalking victimization

There is no uniform denition of cyberstalking victimization

in the United States. However, the federal denition and

many state denitions include similar elements. The federal

legal denition of cyberstalking was expanded under

the Violence Against Women and Department of Justice

Reauthorization Act of 2005 to include all communications

via software that use the Internet or Internet-based

technologies.

1

In 2013, the denition of cyberstalking was

expanded to include “any interactive computer service or

electronic communication service,” including interstate and

foreign electronic communication.

2

Throughout this report, estimates are reported for victims

of stalking with technology. In the 2019 Supplemental

Victimization Survey (SVS), stalking with technology

includes unwanted phone calls or text messages,

as well as unwanted behaviors using electronic

communication or technology (e.g., social media or GPS).

Cyberstalking includes stalking through any form of

information technology, like online platforms or location

tracking devices, and excludes making unwanted phone

calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages.

Denitions and laws vary for cyberstalking and may or

may not include sending text messages using mobile

devices. However, the SVS cannot separate making

phone calls or leaving voice messages from sending text

messages. (See Methodology for details on the wording of

SVS items.)

In 2019, an estimated 0.4% (936,310 persons) of all U.S.

residents age 16 or older were victims of cyberstalking,

and about 0.2% (538,690 persons) received unwanted

emails or messages using the Internet or social

media (table 3). Approximately 0.1% of all persons

age 16 or older were monitored using social media

(304,890 persons) or had unwanted information posted

about them on the Internet (326,540 persons). About

0.1% of all persons age 16 or older were spied on using

technologies (310,350 persons) or had their whereabouts

tracked with an electronic device or application

(168,150 persons).

1

Violence Against Women and Department of Justice

Reauthorization Act of 2005, 109 U.S.C. § 3402 et seq. (2005).

https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-109hr3402enr/pdf/BILLS-

109hr3402enr.pdf

2

Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013, 113 U.S.C.

§ 2261A et seq. (2013). https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-

113s47enr/pdf/BILLS-113s47enr.pdf

Table 3

Prevalence of cyberstalking, by type of cyberstalking behavior, 2019

Type of cyberstalking behavior

Number of

cyberstalking victims

a

Percent of all persons

b

Total 936,310 0.4%

Sent victim unwanted emails/messages using the Internet or social media 538,690 0.2

Monitored activities using social media 304,890 0.1

Posted/threatened to post inappropriate/unwanted/personal information

c

326,540 0.1

Spied on or monitored activities using technology 310,350 0.1

Tracked whereabouts with an electronic device/application 168,150 0.1

Note: Estimates in this table include victims who experienced cyberstalking, which includes stalking through any form of information technology

and excludes making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages. Details may not sum to totals because victims could

experience more than one type of cyberstalking behavior. The total population age 16 or older in 2019 was 260,731,490. See appendix table 6 for

standard errors. See Methodology for question wording for the types of cyberstalking behaviors.

a

Number of persons age 16 or older who experienced cyberstalking victimization in the past year.

b

Percentage of persons age 16 or older who experienced cyberstalking victimization in the past year.

c

Includes posting private photographs, videos, or rumors.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 7

Persons ages 20 to 24 were stalked more often than

persons ages 35 or older

In 2019, the prevalence of stalking was higher among

females (1.8%) than males (0.8%) (table 4). Compared

to white persons, stalking prevalence was higher among

persons of two or more races (3.9%) and persons who

were American Indian or Alaska Native (3.3%). Rates

of stalking were lower for black persons (1.1%) and

persons who were Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Other

Pacic Islander (1.1%) compared to white persons

(1.3%). ere was no statistically signicant dierence

in the prevalence of stalking between white persons and

Hispanic persons.

Persons ages 20 to 24 (2.0%) were stalked more oen

than persons in age groups over 35. Separated persons

were stalked more oen (3.8%) than persons of all other

marital statuses. Persons living in households earning

less than $25,000 annually (2.1%) were stalked more

oen than persons living in households earning $25,000

or more annually.

Table 4

Prevalence of stalking, by demographic characteristics of

victims, 2019

Victim demographic characteristic

Number

of victims

a

Percent of

all persons

b

Total 3,419,710 1.3%

Sex

Male* 982,080 0.8%

Female 2,437,630 † 1.8 †

Race/ethnicity

White

c

* 2,188,360 1.3%

Black

c

342,430 † 1.1 ‡

Hispanic 515,110 † 1.2

Asian/Native Hawaiian/

Other Pacic Islander

c,d

179,840 † 1.1 ‡

American Indian/Alaska Native

c

48,940 † 3.3 †

Two or more races

c

145,030 † 3.9 †

Age

16–19 239,650 † 1.5% ‡

20–24* 426,840 2.0

25–34 796,270 † 1.7

35–49 942,610 † 1.5 †

50–64 690,500 † 1.1 †

65 or older 323,830 ‡ 0.6 †

Marital status

Never married 1,394,440 † 1.7% †

Married 973,100 † 0.8 †

Widowed 126,680 ‡ 0.8 †

Divorced 719,900 † 2.5 †

Separated* 197,250 3.8

Household income

Less than $25,000* 891,650 2.1%

$25,000–$49,999 816,730 1.3 †

$50,000–$99,999 1,024,140 1.2 †

$100,000–$199,999 536,110 † 1.1 †

$200,000 or more 151,080 † 0.9 †

Note: Details may not sum to totals due to rounding. See appendix table 7

for standard errors.

*Comparison group.

†Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 95% condence level.

‡Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 90% condence level.

a

Number of persons age 16 or older who experienced stalking

victimization in the past year.

b

Percentage of persons age 16 or older who experienced stalking

victimization in the past year.

c

Excludes persons of Hispanic origin (e.g., “white” refers to non-Hispanic

white persons and “black” refers to non-Hispanic black persons).

d

Categories are not shown separately due to small numbers of sample cases.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey,

Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 8

Most stalking victims knew their stalker

In 2019, about 67% of victims of stalking knew their

stalker in some capacity (table 5). Victims were more

likely to be stalked by a well-known or casual acquaintance

(38%) or current or ex-intimate partner (25%) than by a

relative (5%) (statistical testing performed and not shown).

Victims of both traditional stalking and stalking with

technology were more likely to be stalked by a known

oender (81%) than victims of traditional stalking only

(56%) or stalking with technology only (54%). Victims

of both stalking types were three times as likely to

be stalked by an intimate partner (35%) as victims of

traditional stalking only (11%) and two times as likely as

victims of stalking with technology only (18%).

In 2019, about 18% of victims were stalked by a stranger

and 14% were unable to identify their relationship to the

oender. Victims of traditional stalking were more likely

to be stalked by a stranger (30%) than victims of stalking

with technology (19%) or both types of stalking (12%).

Victims of stalking with technology were more likely to

not know their relationship to the oender (26%) than

victims of traditional stalking (13%) or both stalking

types (6%).

Table 5

Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking and victim-oender relationship, 2019

Type of victim-oender relationship Total stalking Traditional stalking only

a

Stalking with

technology only

b

Both traditional

stalking and stalking

with technology

c

*

Total 100% 100% 100% 100%

Known 67.2% 55.8% † 54.3% † 80.9%

Intimate partner

d

24.8 11.2 † 17.6 † 35.5

Current partner 5.8 2.8 ! 5.6 7.2

Ex-partner 19.0 8.4 † 12.0 † 28.3

Other relative 4.8 6.2 4.6 4.3

Well-known/casual acquaintance 37.6 38.4 32.1 † 41.1

Friend/ex-friend 7.2 6.6 9.3 6.0

Acquaintance/in-law or relative of spouse

or ex-spouse/friend of one of the

oenders/other 12.6 9.6 ‡ 11.1 15.0

Roommate/housemate/boarder/neighbor 8.4 14.4 ‡ 4.3 † 8.8

Professional acquaintance

e

9.4 7.9 7.5 ‡ 11.4

Stranger 18.1% 30.1% † 19.3% † 12.2%

Unknown

f

13.9% 12.8% † 26.0% † 6.0%

Number of victims 3,419,710 681,240 1,118,890 1,619,580

Note: Details may not sum to totals due to missing data, which occurred in about 1% of all stalking victimizations. See appendix table 8 for standard errors.

*Comparison group. Percentage of victims by victim-oender relationship compared to each stalking type and not total stalking.

†Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 95% condence level.

‡Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 90% condence level.

! Interpret data with caution. Estimate is based on 10 or fewer sample cases, or coecient of variation is greater than 50%.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted items; or

harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying using

technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet;

sending emails or messages using the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

d

Includes current or former spouses or partners, boyfriends or girlfriends, or other romantic or sexual partners.

e

Includes schoolmates, supervisors (current or former), coworkers (current or former), teachers or school sta, customers or clients, patients, students, and

employees (current or former).

f

Includes unknown victim-oender relationships and unknown number of oenders.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 9

Twenty-four percent of victims said the stalking

behaviors lasted 2 years or more

In 2019, nearly 44% of stalking victims experienced

stalking behaviors that lasted 1 month to less than

1 year (table 6). Twenty-four percent of victims said the

stalking behaviors lasted 2 years or more. A greater share

of traditional stalking victims (28%) and stalking with

technology victims (20%) experienced stalking behaviors

for less than 1 month compared to victims of both types

of stalking (12%).

For more than half (58%) of stalking victims, the

stalking behaviors occurred 2 to 10 times during the

victimization. A smaller share of victims of both types

of stalking (49%) said the behaviors happened 2 to 10

times during the victimization compared to victims

of traditional stalking only (81%) and stalking with

technology only (57%). Victims of both stalking types

(25%) were more than three times as likely to say the

stalking behaviors happened 11 to 50 times as victims

of traditional stalking only (7%). Fourteen percent of

victims of both stalking types said the stalking behaviors

happened too many times to count.

Table 6

Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking and duration and frequency of stalking, 2019

Stalking duration and frequency Total stalking Traditional stalking only

a

Stalking with

technology only

b

Both traditional stalking and

stalking with technology

c

*

Total 100% 100% 100% 100%

Duration

Less than 1 month 17.6% 27.8% † 20.0% † 11.6%

1 month to less than 1 year 43.7 39.1 42.6 46.4

1 year to less than 2 years 12.5 10.2 13.2 12.9

2 years or more 24.0 21.5 21.5 26.8

Unknown 2.1 1.4 ! 2.7 1.9

Frequency

2 to 10 times

d

58.1% 81.1% † 57.1% † 49.1%

11 to 50 times 19.2 6.8 † 18.7 ‡ 24.8

More than 50 times 7.2 3.0 ! 8.3 8.1

Too many times to count 10.8 2.8 ! 11.4 13.8

Don’t know/don’t remember 4.3 5.4 4.5 3.7

Number of victims 3,419,710 681,240 1,118,890 1,619,580

Note: Details may not sum to totals due to missing data, which occurred in less than 1% of all stalking victimizations. See appendix table 9 for standard errors.

*Comparison group. Percentage of victims by duration and frequency of stalking compared to each stalking type and not total stalking.

†Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 95% condence level.

‡Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 90% condence level.

! Interpret data with caution. Estimate is based on 10 or fewer sample cases, or coecient of variation is greater than 50%.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted items; or

harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying using

technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet;

sending emails or messages using the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

d

Unwanted contacts or behaviors had to happen more than once for the respondent to screen into the Supplemental Victimization Survey.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 10

Victims of both stalking types were more than twice

as likely as other stalking victims to have applied for

a restraining, protection, or no-contact order

Stalking victims took a variety of actions to protect

themselves from the oender. In 2019, about 24% of

stalking victims changed their day-to-day activities to

protect themselves or stop the unwanted contacts or

behaviors (table 7). A greater percentage of victims of

both traditional stalking and stalking with technology

(34%) than victims of traditional stalking only (21%)

or stalking with technology only (13%) changed their

day-to-day activities.

Victims of both stalking types (28%) and victims of

traditional stalking only (28%) were more likely to

have engaged in self-defensive actions or other security

measures than victims of stalking with technology only

(12%). Victims of both types of stalking were more than

two times as likely to have applied for a restraining,

protection, or no-contact order (13%) as victims of

traditional stalking only (6%) or stalking with technology

only (5%).

Table 7

Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking and victim’s self-protective actions, 2019

Self-protective action taken Total stalking Traditional stalking only

a

Stalking with

technology only

b

Both traditional

stalking and stalking

with technology

c

*

Any self-protective action taken 77.7% 51.2% 81.5% 86.2%

Changed day-to-day activities 24.2 20.8 † 12.5 † 33.6

Blocked unwanted calls/messages/other

communications 62.6 20.2 † 73.8 72.6

Self-defensive action/security measure

d

22.9 27.5 12.3 † 28.3

Changed personal information 26.8 7.2 † 28.3 34.1

Applied for a restraining/protection/

no-contact order 8.8 5.9 † 5.0 † 12.5

Number of victims 3,419,710 681,240 1,118,890 1,619,580

Note: Details may not sum to 100% because victims could take more than one self-protective action. See appendix table 10 for standard errors.

*Comparison group. Percentage of victims who took self-protective actions compared to each stalking type and not total stalking.

†Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 95% condence level.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted items; or

harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying using

technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet;

sending emails or messages using the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

d

Includes taking self-defense or martial arts classes, getting pepper spray, getting a gun or other weapon, or changing or installing new locks or security

system.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 11

67% of victims of both types of stalking were fearful

of being killed or physically harmed

More than three-hs (61%) of stalking victims were

fearful of not knowing what would happen next as a

consequence of the stalking victimization (table 8).

A greater share of victims of both traditional stalking

and stalking with technology (67%) than victims

of traditional stalking only (52%) or stalking with

technology only (30%) were fearful of being killed or

physically harmed as a result of the stalking. Victims of

both stalking types were also more fearful of someone

close to them being harmed; losing their job, social

network, peers, friends, or freedom; the behaviors never

stopping; not knowing what would happen next; or

losing their mind.

Table 8

Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking and victim’s fears, 2019

Victim’s fear Total stalking Traditional stalking only

a

Stalking with

technology only

b

Both traditional

stalking and stalking

with technology

c

*

Being killed or physical/bodily harm 51.8% 51.6% † 29.7% † 67.0%

Being killed 15.7 13.7 † 8.0 † 22.0

Physical/bodily harm 36.0 38.0 21.8 † 45.0

Someone close to victim being harmed 32.3% 31.9% ‡ 22.1% † 39.5%

Loss of job or job opportunities/freedom/

social network/peers/friends 57.2% 37.2% † 42.3% † 76.0%

Loss of job/job opportunities 16.6 8.7 † 13.9 † 21.8

Loss of freedom 24.5 21.2 † 13.9 † 33.3

Loss of social network/peers/friends 16.1 7.3 † 14.5 † 21.0

Behaviors never stopping 55.1% 44.9% † 47.6% † 64.5%

Not knowing what would happen next 61.2% 58.9% † 50.1% † 69.7%

Losing one’s mind 19.1% 12.5% † 14.5% † 25.2%

Number of victims 3,419,710 681,240 1,118,890 1,619,580

Note: Details may not sum to 100% because victims could experience more than one type of fear. See appendix table 11 for standard errors.

*Comparison group. Percentage of victims by type of fear compared to each stalking type and not total stalking.

†Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 95% condence level.

‡Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 90% condence level.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted items; or

harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying using

technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet;

sending emails or messages using the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 12

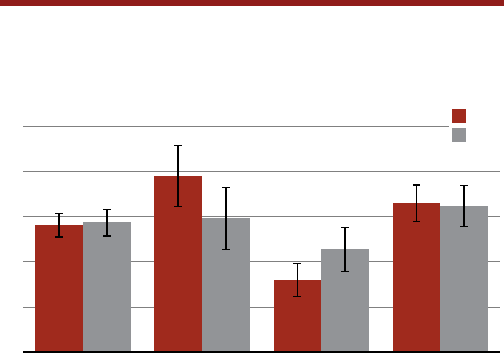

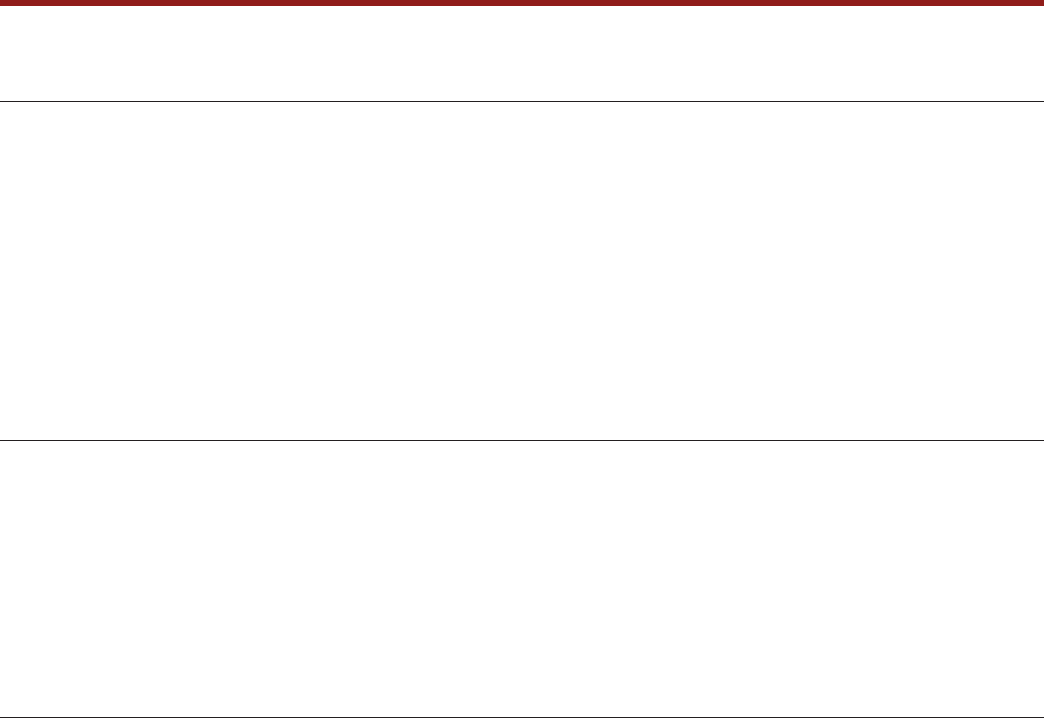

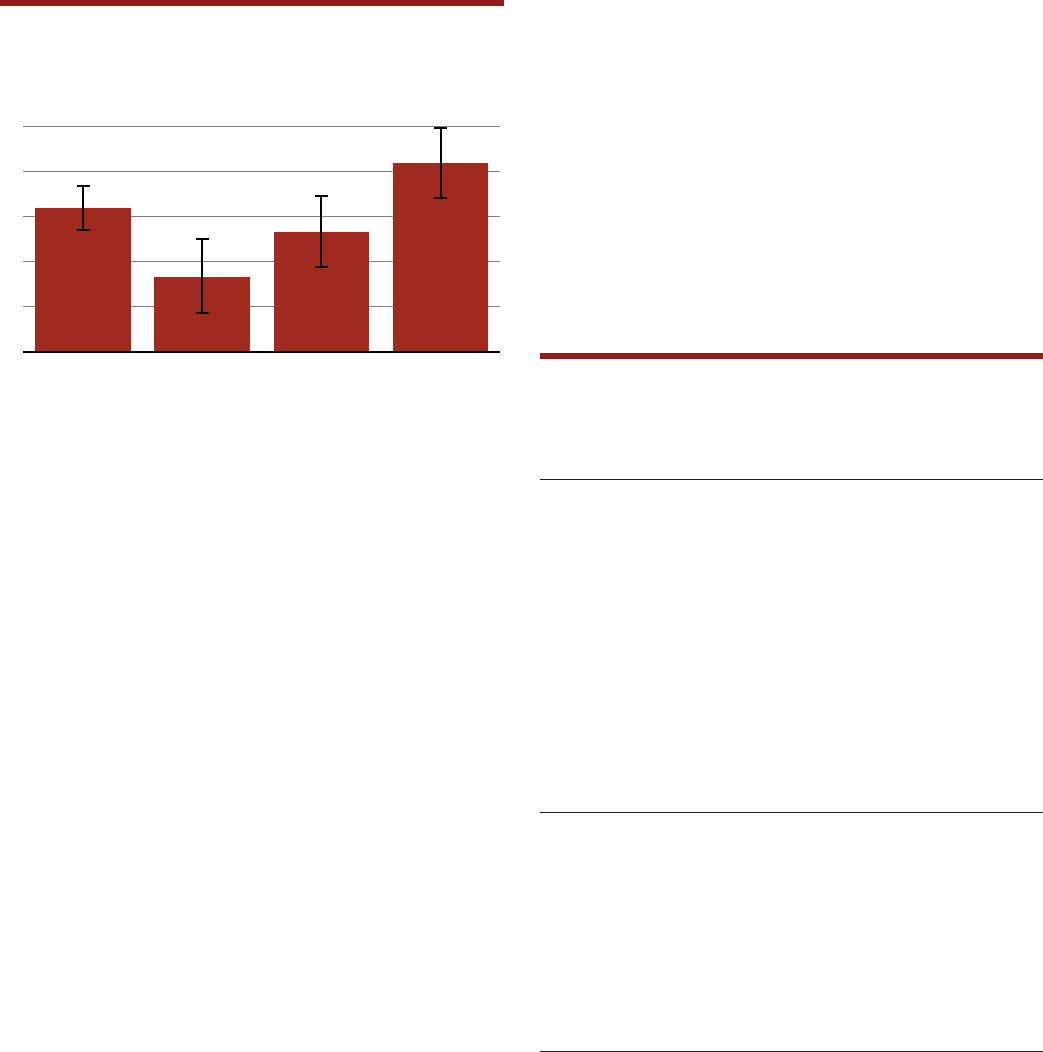

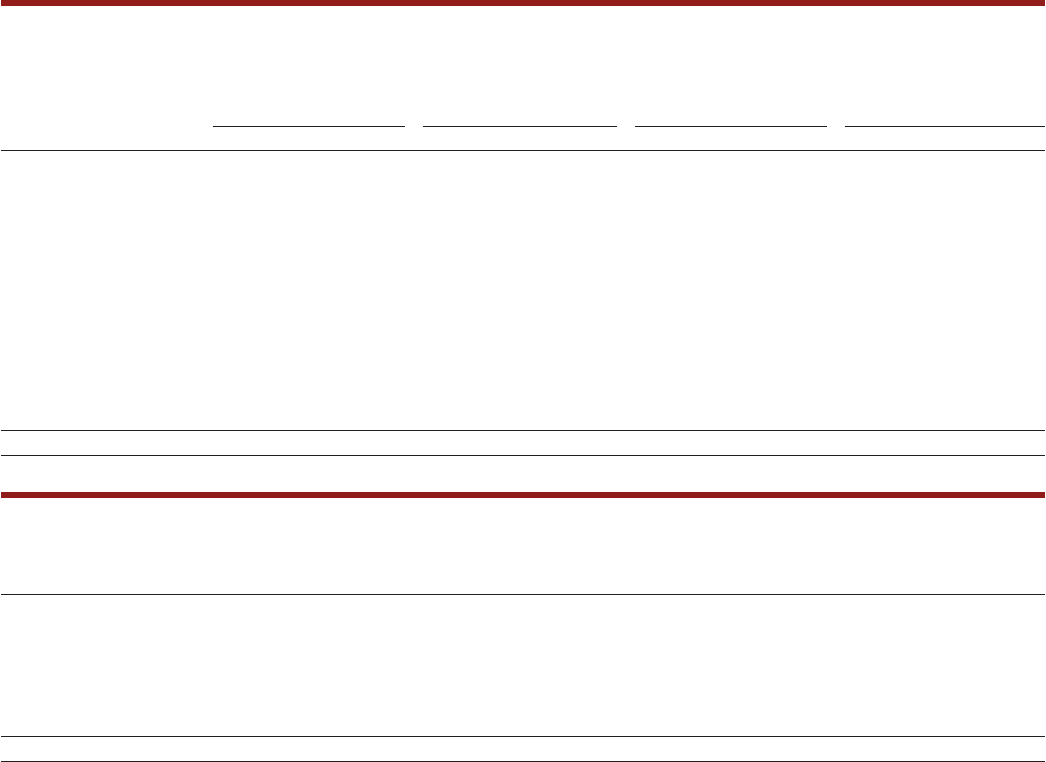

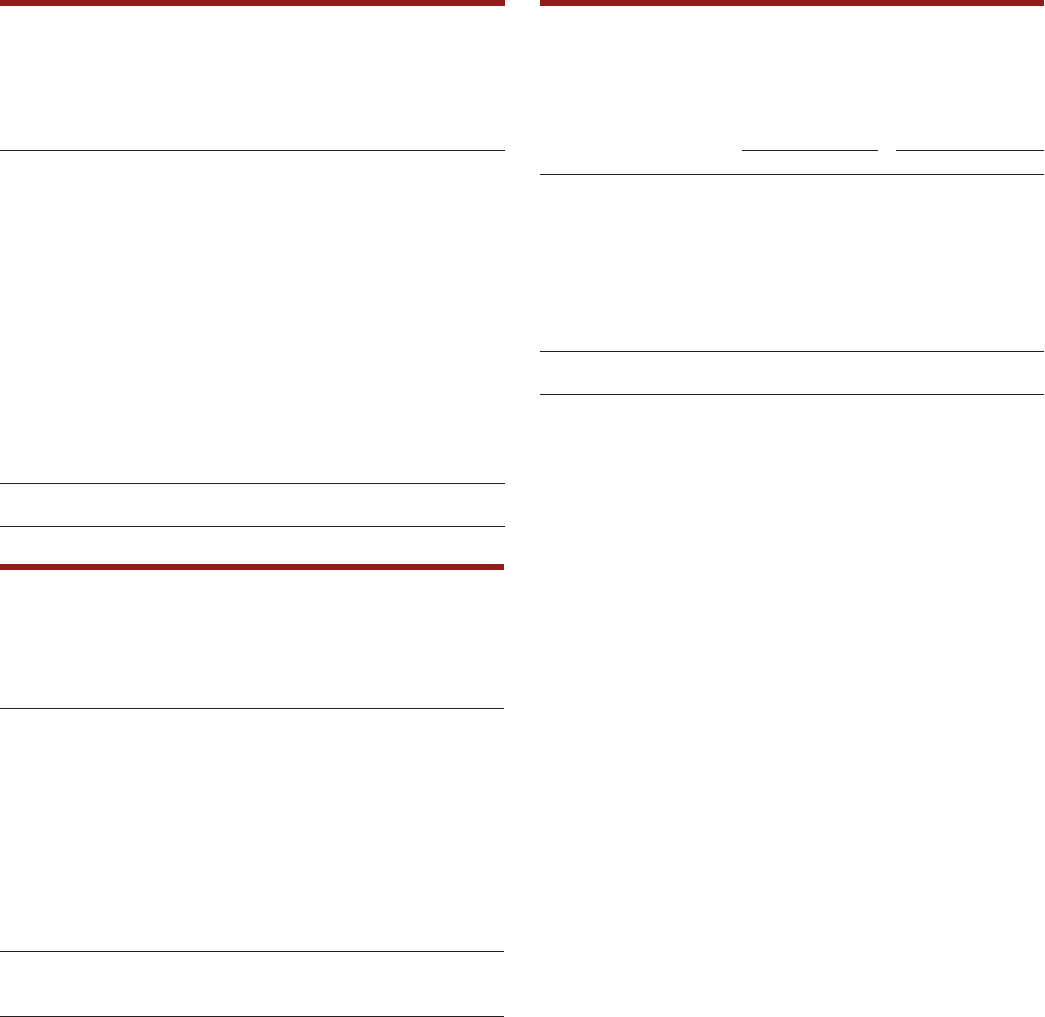

About 1 in 6 stalking victims sought assistance from

a victim service provider

Victim service providers (VSPs) are public or private

organizations that provide assistance to crime victims.

In 2019, about 16% of all stalking victims sought such

services (gure 3). A greater share (21%) of victims of

both traditional stalking and stalking with technology

sought victim services than victims of traditional stalking

only (8%) or stalking with technology only (13%).

Figure 3

Percent of stalking victims who sought victim services, by

type of stalking, 2019

Percent of stalking victims

0

5

10

15

20

25

Both traditional

stalking and stalking

with technology

c

*

Stalking with

technology only

b

Traditional

stalking only

a

Total

†

†

Note: Estimates include 95% condence intervals. See appendix table 12

for estimates and standard errors.

*Comparison group. Percentage of victims who sought victim services

compared to each stalking type and not total stalking.

†Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 95% condence level.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking

into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted

items; or harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted

phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying

using technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device

or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on

the Internet; sending emails or messages using the Internet; or monitoring

activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey,

Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

More than 60% of stalking victims who sought

and received victim services obtained counseling

or therapy

VSPs provide a variety of services to victims of crime.

In 2019, 74% of stalking victims who sought services

received them (table 9). Of the stalking victims who

sought and received victim services, about 62% obtained

counseling or therapy from a VSP. About 1 in 3 (35%)

received legal or court services, and about 1 in 4 (26%)

received shelter/safehouse services or safety planning

services. Stalking victims also received assistance in

getting a restraining, protection, or no-contact order

(24%); a risk or threat assessment (18%); crisis hotline

counseling (14%); and medical advocacy (8%).

Nearly one-quarter (23%) of stalking victims who sought

victim services did not receive them. Victims may not

receive services for a variety of reasons, including the

services not being available in the victim’s area, the VSP

not being able to accommodate the victim, language

barriers between the victim and VSP, and the victim not

being eligible for services for some reason (not shown

in table).

Table 9

Percent of stalking victims who sought and received

victim services, by type of service received, 2019

Type of victim service

Percent of

stalking victims

Victim services were received

a,b

73.7%

Counseling/therapy 61.7

Legal/court services 34.5

Shelter/safehouse service or safety planning 26.4

Assistance getting a restraining/protection/

no-contact order 23.7

Other type of service 21.6

Risk/threat assessment 18.5

Crisis hotline counseling 13.7

Medical advocacy 7.8

Short-term/emergency nancial assistance 7.0

Federal/state victim compensation 3.1 !

Victim services were not received

a

23.3%

Number of victims who sought victim services 544,500

Note: Details may not sum to totals due to missing data and because

victims could receive more than one service. For 3% of stalking victims

who sought victim services, it was unknown whether they received any

services. See appendix table 13 for standard errors.

! Interpret data with caution. Estimate is based on 10 or fewer sample

cases, or coecient of variation is greater than 50%.

a

Percentage denominator is the total number of victims who sought

victim services.

b

For all victim service types listed, percentage denominator is the total

number of victims who received victim services.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey,

Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 13

Methodology

Data collection

e U.S. Census Bureau carries out the National Crime

Victimization Survey (NCVS) and its Supplemental

Victimization Survey (SVS) on behalf of the Bureau of

Justice Statistics (BJS). e NCVS collects data on crimes

reported or not reported to police against persons age

12 or older from a nationally representative sample of

U.S. households. e sample includes persons living in

group quarters (such as dormitories, rooming houses,

and religious group dwellings) and excludes persons

living in military barracks and institutional settings (such

as correctional or hospital facilities) and persons who

are homeless.

From July 1, 2019 through December 31, 2019, persons

age 16 or older in sampled NCVS households received

the SVS at the end of the NCVS interview. Proxy

responders to the NCVS interview did not receive the

SVS. All NCVS and SVS interviews were conducted

using computer-assisted personal interviewing, either

by telephone or an in-person visit. Of the 141,300

original NCVS-eligible respondents age 16 or older,

approximately 105,000 completed the SVS questionnaire,

resulting in a response rate of 74.3%.

e combined SVS unit response rate for NCVS

households, NCVS persons, and SVS persons was 51.9%.

Because of the level of nonresponse, a bias analysis was

conducted. e results indicated that there was little to

no substantive bias due to nonresponse in the nal SVS

weighted estimates.

e SVS collected individual-level data on the

prevalence of stalking victimization among persons,

the characteristics of stalking victims, and the patterns

of reporting to the police and other authorities.

Respondents were asked whether they were stalked

during the 12 months prior to the interview. For

example, persons interviewed in July 2019 were asked

about stalking victimization that occurred between

July 2018 and June 2019. Stalking victimizations were

classied by the year of the survey and not by the year of

the victimization.

Persons who reported a stalking victimization were

asked more detailed questions about their victimization

and their responses to it, such as the victim-oender

relationship, physical and emotional consequences to the

victim, self-protective measures taken, and the response

of the criminal justice system. For most sections of the

survey, the SVS asked stalking victims to think about

the person or persons who committed these unwanted

contacts or behaviors in the last 12 months when

answering questions.

Changes to the measurement of stalking

victimization in the SVS

BJS rst collected data from the SVS in 2006. e

supplement was designed in 2005, shortly before federal

stalking laws changed under the Violence Against

Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act

of 2005 (VAWA). VAWA expanded the legal denition of

cyberstalking to include all communications via soware

that use the Internet or Internet-based technologies. e

law also expanded the victim-harm requirement to

include substantial emotional harm to the victim in

addition to actual or reasonable fear.

3

In 2013, VAWA was amended to address presence,

intimidation, substantial emotional distress, and

cyberstalking.

4

First, the law was expanded to apply

to any person stalking another person within U.S.

waters, territorial jurisdictions, or states. Second, the

stalker’s intent previously had to be to kill, injure, harass,

or place a person under surveillance, and this was

expanded to include intimidation. ird, the law was

expanded to include acts that caused, were intended

to cause, or would be reasonably expected to cause

substantial emotional distress. Finally, the denition of

cyberstalking was expanded to include any electronic

communication, including interstate and foreign

electronic communication.

In 2015, BJS redesigned the 2006 SVS instrument to

incorporate the 2005 and 2013 updates to VAWA. e

redesigned instrument began with a series of screener

questions about each element of VAWA’s stalking

denition. e screener included expanded questions

about unwanted contacts and behaviors associated

with traditional stalking and stalking with technology.

Separate screener questions were also developed to

measure victim responses of fear and substantial

emotional distress.

If the respondent’s answers identied them as a stalking

victim, the survey instrument included additional

questions focused on details of the stalking victimization.

In addition to the changes to the instrument, BJS lowered

the minimum age of survey respondents from 18 to 16.

3

Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization

Act of 2005, 109 U.S.C. § 3402 et seq. (2005). https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/

pkg/BILLS-109hr3402enr/pdf/BILLS-109hr3402enr.pdf

4

Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013, 113 U.S.C.

§ 2261A et seq. (2013). https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-

113s47enr/pdf/BILLS-113s47enr.pdf

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 14

Due to these changes, estimates from the 2016 and 2019

SVS cannot be compared to estimates from the 2006

SVS. Minor instrument revisions were made for the 2019

SVS, so estimates from the 2019 SVS can be compared to

estimates from the 2016 SVS.

e 2019 SVS can be used to estimate stalking

prevalence for persons age 16 or older in the United

States. e stalking screener questions allow for

better measurement of the types of stalking behaviors

experienced by respondents, especially stalking with

technology. Improvements to the questions about the

stalking incident enhanced the ability to describe the

characteristics of stalking victimizations.

Dening stalking victimization

ere is no nationwide denition of stalking

victimization. However, the federal denition and

many state denitions include similar components. In

developing the SVS, BJS used the expertise of a range

of federal (including the Department of Justice’s Oce

on Violence Against Women and Oce for Victims

of Crime) and private sources in the elds of criminal

justice and victim services. See Stalking Victimization,

2016 (NCJ 253526, BJS, April 2021) for more information

on state stalking laws.

Measuring stalking with the SVS

Because the SVS denition of stalking is aligned with the

federal denition, to be classied as a victim of stalking

in the SVS, the respondent must have experienced

a repeated course of conduct that caused them to

experience fear or substantial emotional distress or that

would cause a reasonable person to experience fear or

substantial emotional distress.

e SVS screener questions collected the following

elements of that denition: (1) unwanted contacts

or behaviors, (2) a repeated course of conduct (i.e.,

experiencing the same behavior or contact more than

once or experiencing two or more dierent behaviors one

time), (3) actual fear, (4) substantial emotional distress,

and (5) reasonable fear.

Questions used to measure stalking behaviors

SQ1. In the past 12 months, have you experienced

any unwanted contacts or behaviors? By that I mean

has anyone—

a. Followed you around and watched you?

b. [Has anyone] Snuck into your home, car, or any place

else and did unwanted things to let you know they had

been there?

c. [Has anyone] Waited for you at your home, work,

school, or any place else when you didn’t want

them to?

d. [Still thinking about unwanted contacts and behaviors,

in the past 12 months, has anyone] Shown up, ridden

or driven by places where you were when they had no

business being there?

e. [Has anyone] Le or sent unwanted items, cards,

letters, presents, owers, or any other unwanted items?

f. [Has anyone] Harassed or repeatedly asked your

friends or family for information about you or

your whereabouts?

Now I want to ask about unwanted contacts or behaviors

using various technologies, such as your phone, the

Internet, or social media apps. Again, please DO NOT

include bill collectors, solicitors, or other sales people. In

the past 12 months, has anyone—

g. Made unwanted phone calls to you, le voice

messages, sent text messages, or used the phone

excessively to contact you?

h. [Has anyone] Spied on you or monitored your

activities using technologies such as a listening

device, camera, or computer or cell phone

monitoring soware?

i. [Still thinking about unwanted contacts or behaviors,

in the past 12 months, has anyone] Tracked your

whereabouts with an electronic tracking device or

application, such as GPS or an application on your

cell phone?

j. [Has anyone] Posted or threatened to post

inappropriate, unwanted, or personal information

about you on the Internet, including private

photographs, videos, or spreading rumors?

k. [Has anyone] Sent unwanted e-mails or messages

using the Internet, for example, using social media

apps or websites like Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook?

l. [Has anyone] Monitored your activities using social

media apps like Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook?

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 15

Question used to measure repetition

SQ2. Has anyone done (this/any of these things) to you

more than once in the past 12 months?

If the respondent answered ‘no’ to this question, but had

experienced more than one of the stalking behaviors, the

interview continued and they were asked about fear and

emotional distress.

Questions used to measure actual fear and substantial

emotional distress

SQ3a. Did any of these unwanted contacts or behaviors

make you fear for your safety or the safety of someone

close to you?

SQ3b. Did any of these unwanted contacts or behaviors

cause you substantial emotional distress?

Questions used to measure reasonable fear

Now I have some additional questions about the time

someone {behavior

1

}, {behavior

2

}, and {behavior

x

...}.

inking about the person or persons who committed

these unwanted contacts or behaviors in the past

12 months, did any of the following occur—

SQ4. Did this person or these people damage or attempt

to damage or destroy property belonging to you or

someone else in your household?

SQ5. [inking about the person or persons who

committed these unwanted contacts or behaviors in the

past 12 months] Did this person or these people—

Physically attack you?

Attempt to physically attack you?

reaten to physically attack you?

SQ6. [inking about the person or persons who

committed these unwanted contacts or behaviors in the

past 12 months] Did this person or these people—

Physically attack someone close to you or a pet?

Attempt to physically attack someone close to you or

a pet?

reaten to physically attack someone close to you or

a pet?

Of the 3.4 million stalking victims in 2019, more than

2.1 million (62%) experienced fear and 2.4 million (69%)

experienced substantial emotional distress (table 10).

About 1.6 million (45%) victims had an experience

that would, by denition, cause a reasonable person to

experience fear, including property damage or an attack.

Table 10

Number and percent of stalking victims, by component

of stalking denition, 2019

Component of

stalking denition

Number of

stalking victims

a

Percent of

stalking victims

Total 3,419,710 100%

Actual fear

b

* 2,131,180 62.3%

Emotional distress

c

2,373,600 ‡ 69.4% †

Reasonable fear

d

1,553,560 † 45.4% †

Damage/attempted damage

or destruction of property* 610,940 17.9

Threatened/attempted/

completed attack on victim 309,470 † 9.0 †

Threatened/attempted/

completed attack on pet or

someone close to victim 103,280 † 3.0 †

Two or more reasonable fear

components

e

529,870 15.5

Note: Details do not sum to totals because victims could experience

more than one component of the stalking denition (i.e., fear, emotional

distress, or reasonable fear). See appendix table 14 for standard errors.

*Comparison group.

†Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 95% condence level.

‡Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 90% condence level.

a

Number of persons age 16 or older who experienced stalking victimization

in the past year.

b

Includes stalking where the victim reported that the unwanted behaviors

made them fear for their safety or the safety of someone close to them.

c

Includes stalking where the victim reported that the unwanted behaviors

caused them substantial emotional distress.

d

Includes stalking that involved damage or attempted damage or

destruction of property; or threatened, attempted, or completed attacks

on the victim, someone close to them, or a pet.

e

Includes stalking that involved multiple types of reasonable fear

components (i.e., damage or attempted damage or destruction of

property; or threatened, attempted, or completed attacks on the victim,

someone close to them, or a pet).

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey,

Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 16

Standard error computations

When national estimates are derived from a sample,

caution must be taken when comparing one estimate

to another. Although one estimate may be larger

than another, estimates based on a sample have some

degree of sampling error. e sampling error of an

estimate depends on several factors, including the

amount of variation in the responses and the size of the

sample. When the sampling error around an estimate

is accounted for, dierences in estimates may not be

statistically signicant.

One measure of the sampling error associated with

an estimate is the standard error. e standard error

may vary from one estimate to the next. Generally, an

estimate with a small standard error provides a more

reliable approximation of the true value than an estimate

with a larger standard error. Estimates with relatively

large standard errors are associated with less precision

and reliability and should be interpreted with caution.

Generalized variance functions (GVF) parameters were

used to generate standard errors for each point estimate

(e.g., numbers, percentages, and rates) in this report. To

generate standard errors around prevalence estimates

from the SVS, the U.S. Census Bureau produces GVF

parameters for BJS. e GVFs account for aspects of the

NCVS’s complex sample design and represent the curve

tted to a selection of individual standard errors based

on the Balanced Repeated Replication technique.

BJS conducted statistical tests to determine whether

dierences in estimated numbers, percentages, and rates

in this report were statistically signicant once sampling

error was accounted for. Using statistical analysis

programs developed specically for the NCVS, all

comparisons in the text were tested for signicance. e

primary test procedure used was the Student’s t-statistic,

which tests the dierence between two sample estimates.

Findings described in this report as higher, lower, or

dierent passed a test at either the 0.05 level (95%

condence level) or 0.10 level (90% condence level) of

statistical signicance. Figures and tables in this report

should be referenced for testing on specic ndings.

Caution is required when comparing estimates not

explicitly discussed in this report.

Estimates and standard errors of the estimates in this

report may be used to generate a condence interval

around the estimate as a measure of the margin of error.

e following example illustrates how standard errors

may be used to generate condence intervals:

Based on the SVS, in 2019 an estimated 1.3% of

all persons age 16 or older experienced stalking

victimization. (See appendix table 1.) Using GVFs,

BJS determined that the estimated prevalence rate has

a standard error of 0.05%. (See appendix table 15.) A

condence interval around the estimate is generated

by multiplying the standard error by ± 1.96 (the t-score

of a normal, two-tailed distribution that excludes 2.5%

at either end of the distribution). erefore, the 95%

condence interval around the 1.3% estimate is 1.3 ±

(0.05 × 1.96) or (1.22% to 1.40%). In other words, if

BJS used the same sampling method to select dierent

samples and computed an interval estimate for each

sample, it would expect the true population parameter

(percentage of stalking victims) to fall within the

interval estimates 95% of the time.

For this report, BJS also calculated a coecient of

variation (CV) for all estimates, representing the ratio

of the standard error to the estimate. CVs (not shown

in tables) provide another measure of reliability and a

means for comparing the precision of estimates across

measures with diering levels or metrics.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 17

appendix Table 1

Number and percent of persons who were victims of stalking, by type of stalking, 2016

and 2019

a b

Type of stalking

Number of stalking victims Percent of all persons

2016 2019* 2016 2019*

Total 3,788,800 † 3,419,710 1.5% † 1.3%

Any traditional stalking

c

2,472,440 2,300,830 1.0% 0.9%

Traditional stalking only 703,250 681,240 0.3 0.3

Any stalking with technology

d

3,085,550 † 2,738,470 1.2% † 1.1%

Stalking with technology only 1,316,360 † 1,118,890 0.5 † 0.4

Both traditional stalking and

stalking with technology

e

1,769,190 1,619,580 0.7% 0.6%

Note: Details may not sum to totals because victims could experience more than one type of stalking. The

total population age 16 or older was 256,432,020 in 2016 and 260,731,490 in 2019. See appendix table 15 for

standard errors.

*Comparison year.

†Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 95% condence level.

a

Number of persons age 16 or older who experienced stalking victimization in the past year.

b

Percentage of persons age 16 or older who experienced stalking victimization in the past year.

c

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place;

leaving or sending unwanted items; or harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

d

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages,

or sending text messages; spying using technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or

application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet; sending emails or messages using

the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

e

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2016 and 2019.

appendix Table 2

Estimates and standard errors for gure 1: Prevalence of stalking, by type of stalking, 2016 and 2019

Type of stalking

Estimate Standard error

95% condence interval

2016 2019

2016 2019* 2016 2019 Lower bound Upper bound Lower bound Upper bound

Total 1.5% † 1.3% 0.05% 0.05% 1.39% 1.57% 1.22% 1.40%

Traditional stalking only

a

0.3 0.3 0.02 0.02 0.24 0.31 0.22 0.30

Stalking with technology only

b

0.5 † 0.4 0.03 0.03 0.46 0.57 0.38 0.48

Both traditional stalking and

stalking with technology

c

0.7 0.6 0.03 0.03 0.63 0.75 0.56 0.68

Note: The total population age 16 or older was 256,432,020 in 2016 and 260,731,490 in 2019.

*Comparison year.

†Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 95% condence level.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted items; or

harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying using

technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet;

sending emails or messages using the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2016 and 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 18

appendix Table 3

Standard errors for table 1: Persons age 16 or older who were victims of stalking, by type of stalking behavior, 2019

Type of stalking behavior

Number of

stalking victims

Percent of

stalking victims Percent of all persons

Total 120,536 ~ 0.05%

Any traditional stalking 98,651 1.64% 0.04%

Followed or watched 75,170 2.10 0.03

Showed up at/rode by/drove by places 68,629 2.13 0.03

Harassed/repeatedly asked friends/family for information 63,256 2.09 0.02

Waited at home/work/school/any other place 54,759 1.97 0.02

Left/sent unwanted items 45,973 1.76 0.02

Sneaked into home/car/any other place 40,342 1.59 0.02

Any stalking with technology 107,732 1.40% 0.04%

Made unwanted phone calls left voice messages/sent text messages 87,184 1.85 0.03

Sent unwanted emails/messages using the Internet or social media 79,294 1.94 0.03

Monitored activities using social media 60,466 1.82 0.02

Posted/threatened to post inappropriate/unwanted/personal information 57,902 1.77 0.02

Spied on or monitored activities using technology 50,437 1.62 0.02

Tracked whereabouts with an electronic device/application 40,452 1.36 0.02

~Not applicable.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

appendix Table 4

Estimates and standard errors for gure 2: Percent of stalking victims who reported to police, by type of stalking, 2016

and 2019

Type of stalking

Estimate Standard error

95% condence interval

2016 2019

2016 2019* 2016 2019 Lower bound Upper bound Lower bound Upper bound

Total 28.1% 28.7% 1.40% 1.58% 25.34% 30.84% 25.56% 31.75%

Traditional stalking only

a

38.9 ‡ 29.6 3.52 3.55 32.00 45.81 22.64 36.55

Stalking with technology only

b

15.9 † 22.7 1.93 2.54 12.08 19.65 17.75 27.72

Both traditional stalking and

stalking with technology

c

32.9 32.3 2.14 2.36 28.69 37.08 27.71 36.98

*Comparison year.

†Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 95% condence level.

‡Dierence with comparison year is signicant at the 90% condence level.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place; leaving or sending unwanted items; or

harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages, or sending text messages; spying using

technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet;

sending emails or messages using the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2016 and 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 19

appendix Table 5

Standard errors for table 2: Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking, reporting to police, and reason for not

reporting, 2016 and 2019

Total stalking Traditional stalking only

Stalking with

technology only

Both traditional stalking and

stalking with technology

2016 2019 2016 2019 2016 2019 2016 2019

Reported to police 1.40% 1.58% 3.52% 3.55% 1.93% 2.54% 2.14% 2.36%

Not reported to police 1.43% 1.59% 3.54% 3.56% 1.96% 2.56% 2.18% 2.38%

Reason not reported

Not important enough

to report 1.83 2.04 4.66 4.60 2.85 3.42 2.74 3.02

Dealt with it another way 1.80 2.03 4.54 4.41 2.77 3.37 2.77 3.06

Police couldn’t

do anything 1.64 1.95 3.77 4.52 2.67 3.25 2.44 2.84

Police wouldn’t help 1.35 1.63 3.73 3.97 1.94 2.47 2.10 2.50

Other/unknown reason 1.26 1.50 3.45 3.04 1.52 1.72 2.17 2.63

Feared oender 0.91 1.11 2.41 2.93 1.11 1.50 1.58 1.71

Number of victims 117,999 120,536 50,883 53,321 69,637 68,510 80,729 82,598

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2016 and 2019.

appendix Table 6

Standard errors for table 3: Prevalence of cyberstalking, by type of cyberstalking behavior, 2019

Type of cyberstalking behavior

Number of

cyberstalking victims Percent of all persons

Total 62,612 0.02%

Sent unwanted emails/messages using the Internet or social media 47,363 0.02

Monitored activities using social media 35,549 0.01

Posted/threatened to post inappropriate/unwanted/personal information 36,799 0.01

Spied on or monitored activities using technology 35,868 0.01

Tracked whereabouts with an electronic device/application 26,348 0.01

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 20

appendix Table 7

Standard errors for table 4: Prevalence of stalking, by demographic characteristics of

victims, 2019

Victim demographic

characteristic Population age 16 or older

Standard error

Number of victims Percent of all persons

Total 260,731,490 120,536 0.05%

Sex

Male 126,441,250 64,140 0.05%

Female 134,290,240 101,575 0.08

Race/ethnicity

White 163,305,520 96,181 0.06%

Black 31,285,740 37,690 0.12

Hispanic 43,863,500 46,305 0.10

Asian/Native Hawaiian/

Other Pacic Islander 17,106,850 27,254 0.16

American Indian/

Alaska Native 1,484,090 14,175 0.94

Two or more races 3,685,800 24,459 0.65

Age

16–19 16,149,660 31,490 0.19%

20–24 21,412,920 42,118 0.19

25–34 45,537,710 57,692 0.13

35–49 61,677,140 62,824 0.10

50–64 62,651,280 53,686 0.09

65 or older 53,302,790 36,645 0.07

Marital status

Never married 81,158,800 76,577 0.09%

Married 129,503,560 63,843 0.05

Widowed 15,278,790 22,851 0.15

Divorced 28,302,350 54,828 0.19

Separated 5,204,210 28,550 0.54

Household income

Less than $25,000 43,138,530 61,085 0.14%

$25,000–$49,999 64,621,860 58,436 0.09

$50,000–$99,999 85,180,950 65,514 0.08

$100,000–$199,999 50,826,710 47,248 0.09

$200,000 or more 16,963,450 24,967 0.15

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 21

appendix Table 8

Standard errors for table 5: Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking and victim-oender relationship, 2019

Type of victim-oender relationship Total stalking

Traditional

stalking only

Stalking with

technology only

Both traditional stalking and

stalking with technology

Known 1.64% 3.86% 3.03% 1.99%

Intimate partner 1.51 2.45 2.31 2.42

Current partner 0.81 1.28 1.39 1.30

Ex-partner 1.37 2.15 1.97 2.28

Other relative 0.74 1.87 1.27 1.03

Well-known/casual acquaintance 1.69 3.78 2.84 2.49

Friend/ex-friend 0.90 1.93 1.76 1.20

Acquaintance/in-law or relative of spouse or

ex-spouse/friend of one of the oenders/other 1.16 2.29 1.90 1.80

Roommate/housemate/boarder/neighbor 0.97 2.72 1.22 1.43

Professional acquaintance 1.01 2.09 1.60 1.60

Stranger 1.34% 3.56% 2.40% 1.65%

Unknown 1.20% 2.60% 2.66% 1.19%

Number of victims 120,536 53,321 68,510 82,598

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

appendix Table 9

Standard errors for table 6: Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking and duration and frequency of stalking, 2019

Stalking duration and frequency Total stalking Traditional stalking only

Stalking with

technology only

Both traditional stalking

and stalking with technology

Duration

Less than 1 month 1.33% 3.48% 2.43% 1.62%

1 month to less than 1 year 1.73 3.79 3.01 2.52

1 year to less than 2 years 1.15 2.34 2.05 1.69

2 years or more 1.49 3.19 2.49 2.24

Unknown 0.50 0.93 0.98 0.70

Frequency

2 to 10 times 1.73% 3.05% 3.01% 2.53%

11 to 50 times 1.37 1.95 2.37 2.18

More than 50 times 0.90 1.32 1.67 1.38

Too many times to count 1.08 1.27 1.93 1.74

Don’t know/don’t remember 0.70 1.75 1.25 0.96

Number of victims 120,536 53,321 68,510 82,598

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

appendix Table 10

Standard errors for table 7: Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking and victim’s self-protective actions, 2019

Self-protective action taken Total stalking Traditional stalking only

Stalking with

technology only

Both traditional stalking

and stalking with technology

Any self-protective action taken 1.46% 3.89% 2.36% 1.75%

Changed day-to-day activities 1.49 3.15 2.01 2.39

Blocked unwanted calls/messages/other

communications 1.69 3.12 2.68 2.26

Self-defensive action/security measure 1.47 3.47 1.99 2.28

Changed personal information 1.55 2.01 2.74 2.40

Applied for a restraining/protection/

no-contact order 0.98 1.83 1.32 1.67

Number of victims 120,536 53,321 68,510 82,598

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 22

appendix Table 11

Standard errors for table 8: Percent of stalking victims, by type of stalking and victim’s fears, 2019

Victim’s fear Total stalking Traditional stalking only

Stalking with

technology only

Both traditional stalking

and stalking with technology

Being killed or physical/bodily harm 1.75% 3.89% 2.78% 2.38%

Being killed 1.27 2.67 1.64 2.09

Physical/bodily harm 1.68 3.77 2.50 2.52

Someone close to victim being harmed 1.63% 3.62% 2.52% 2.47%

Loss of job or job opportunities/freedom/

social network/peers/friends 1.73% 3.76% 3.00% 2.16%

Loss of job/job opportunities 1.30 2.19 2.10 2.08

Loss of freedom 1.50 3.17 2.10 2.38

Loss of social network/peers/friends 1.28 2.02 2.13 2.06

Behaviors never stopping 1.74% 3.87% 3.04% 2.42%

Not knowing what would happen next 1.71% 3.83% 3.04% 2.33%

Losing one’s mind 1.37% 2.56% 2.14% 2.19%

Number of victims 120,536 53,321 68,510 82,598

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

appendix Table 12

Estimates and standard errors for gure 3: Percent of stalking victims who sought victim

services, by type of stalking, 2019

Type of stalking Percent Standard error

95% condence interval

Lower bound Upper bound

Total 15.9% 1.27% 13.42% 18.42%

Traditional stalking only

a

8.3 † 2.15 4.14 12.56

Stalking with technology only

b

13.3 † 2.06 9.29 17.37

Both traditional stalking and

stalking with technology

c

* 20.9 2.05 16.88 24.93

*Comparison group. Percentage of victims who sought victim services compared to each stalking type and not

total stalking.

†Dierence with comparison group is signicant at the 95% condence level.

a

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: following; sneaking into, waiting, or showing up at a place;

leaving or sending unwanted items; or harassing friends or family about the victim’s whereabouts.

b

Includes the following types of unwanted behaviors: making unwanted phone calls, leaving voice messages,

or sending text messages; spying using technology; tracking the victim’s whereabouts with a tracking device or

application; posting or threatening to post unwanted information on the Internet; sending emails or messages using

the Internet; or monitoring activities using social media.

c

Includes victims who experienced both types of stalking.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, National Crime Victimization Survey, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019.

STALKING VICTIMIZATION, 2019 | FEBRUARY 2022 23

appendix Table 13

Standard errors for table 9: Percent of stalking victims

who sought and received victim services, by type of

service received, 2019

Type of victim service

Percent of

stalking victims

Victim services were received 3.83%

Counseling/therapy 4.92

Legal/court services 4.81

Shelter/safehouse service or safety planning 4.46

Assistance getting a restraining/protection/no-contact

order 4.30

Other type of service 4.16

Risk/threat assessment 3.92

Crisis hotline counseling 3.47

Medical advocacy 2.71