September 2023 Advising Congress on Medicaid and CHIP Policy

Increasing the Rate of Ex Parte Renewals

To renew beneficiaries’ Medicaid coverage, states must first attempt to confirm ongoing eligibility using reliable

information available to the agency without requiring information from the individual. This requirement, also known

as ex parte or administrative renewals, can reduce the administrative burden for states and simplify the process

for beneficiaries (CMS 2022a, 2020). Despite the requirement and the potential for streamlining redeterminations

for states and beneficiaries, the share of renewals completed using the process varies by state and population

(Brooks et al., 2023, Musumeci et al. 2022).

Although conducting ex parte renewals is a long-standing requirement, it has not been a priority area for states

and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) until recently. There has been revived interest in ex

parte renewals, driven in large part by preparations for unwinding the continuous coverage requirements. In

addition, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (CAA, P.L. 117-328) requires states to meet all existing

renewal processing requirements to be eligible for enhanced match.

1

To better understand the barriers to implementing ex parte renewals, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and

Access Commission (MACPAC) contracted with Mathematica to convene a roundtable of state and federal

Medicaid agency representatives and subject matter experts to explore the issues involved and identify ways to

increase the effectiveness of ex parte renewals.

2

Overall, participants agreed that improving the ex parte process

is an important goal, but that there are a number of factors that complicate implementation. Furthermore, while

these changes are technically possible, the issues may take some time to resolve. Specifically, the key themes

that emerged during the roundtable included:

• To successfully conduct ex parte renewals, states need to access a variety of data sources. Some dat

a

s

ources are more important for conducting ex parte renewals with certain Medicaid populations than others.

In addition, the data sources states use, the order in which those data sources are reviewed, and the criteria

for selecting the priority order for data review vary by state.

• Some states face challenges conducting ex parte renewals for several sub-populations of Medicaid

benef

iciaries, in some cases due to additional eligibility criteria that may be more difficult to verify

electronically. This is especially true for beneficiaries whose eligibility is based on age or disability, for whom

asset verification presents particular barriers. Individuals whose income is not readily verified electronically,

those who may be shifting between eligibility groups, and those with medical or health care costs that need t

o

be

verified also face challenges in the ex parte process.

• Roundtable participants agreed that ex parte efforts are less likely to be hindered by technological limitations

than they are by limited resources and competing priorities. States generally must balance a long list of

information technology (IT) system priorities and limited resources and condensed timeframes within which t

o

m

ake them.

• The extent to which states’ Medicaid eligibility systems are integrated with other health and human services

programs can ease renewals for certain beneficiaries, particularly those who also receive these benefits.

Automating ex parte renewal processes can also create efficiencies in the process.

• Roundtable participants expressed an interest in CMS continuing to help states improve their use of ex part

e

r

enewals. Participants strongly supported the flexibilities offered to states during the unwinding of t

he

c

ontinuous coverage requirement and CMS requested that states share data on the effects of thes

e

f

lexibilities on ex parte renewals. Participants also suggested that CMS provide additional guidance,

oversight, and technical assistance to states.

2

• Participants suggested that states and vendors should increase transparency into ex parte policies and

collaboratively share successful approaches. Participants also said that states should review their current

systems, processes, and data to identify opportunities for improvement and engage beneficiaries and other

stakeholders in testing the system.

This brief provides a summary of the roundtable discussion. It begins with a brief background on ex parte before

reviewing the challenges with particular data sources and populations. It then provides a discussion of systems

considerations before concluding with opportunities for improvement.

Background

Federal rules have long required that states first attempt an eligibility renewal using reliable information available

to the states before requesting information from beneficiaries. Reliable information may include information

available in the beneficiary’s account and other more current information available to the state through electronic

data sources and from other benefit programs (CMS 2020).

3

Requirements to use electronic data for verification

predate passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, P.L. 111-148, as amended), but 2012

regulations required states to begin the renewal process by examining existing data before asking individuals for

documentation (CMS 2012).

4, 5

These regulations specifically required states to rely on available and trusted data

to the maximum extent possible when renewing Medicaid eligibility and attempt ex parte renewals for all Medicaid

beneficiaries. This is true for individuals whose eligibility is based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) and

those whose eligibility is determined using non-MAGI-based methods.

6

If the state cannot renew eligibility using

available information, the state must provide beneficiaries eligible on a MAGI basis a prepopulated renewal form

and 30 days to provide any requested information. States have the option of using a prepopulated form for non-

MAGI individuals (42 C.F.R. 435.916).

States vary widely in their rates of successful completion of ex parte renewals and in the extent to which they use

these renewals with certain populations. As of January 2023, of the 43 states continuing to process renewals

during the public health emergency (PHE), 20 reported completing less than 50 percent of renewals using the ex

parte process (Brooks et al. 2023). These rates were similar for individuals eligible on a basis other than modified

adjusted gross income (MAGI) (Musumeci 2022).

7

Ex parte renewals can reduce the burden and costs of redetermining eligibility for beneficiaries and states,

improve the accuracy of eligibility redeterminations, and promote continuity of coverage for eligible people (Box

1). CMS and many states have made ex parte renewals a significant part of their approach to unwinding the

continuous coverage requirement (CMS 2022a). For example, CMS provided guidance on ex parte renewals and

other steps that states can take to promote continuity of coverage during the unwinding period, including adopting

Section 1902(e)(14)(a) waivers to address particular barriers to the ex parte process (CMS 2023c, 2023d, 2022).

8

In addition, multiple states focused on increasing ex parte renewal rates to improve accuracy and reduce

administrative burden by limiting manual processing (ODM n.d., NC DHHS 2023).

Twenty-six states reported

improving their system rules to increase successful rates of ex parte renewals, and seven states have expanded

the number of data sources used for ex parte renewals (Brooks et al. 2023). Twenty-eight states have adopted at

least one new strategy to increase the share of non-MAGI renewals completed ex parte (Musumeci et al. 2022).

3

BOX 1. Opportunities to streamline eligibility redeterminations through ex parte renewals

Reducing burden for beneficiaries. Ex parte renewals are completed without requiring beneficiaries to submit

eligibility information to the state. As long as the information used to renew their Medicaid coverage is correct,

beneficiaries do not need to respond to the renewal notice and their coverage will continue. This reduces

burden for beneficiaries who would otherwise need to provide documentation of their income, assets, or other

relevant eligibility information at least every 12 months.

Promoting continuity of care and reducing costs for beneficiaries and states. Studies show that state use

of ex parte renewals reduces churn—defined as a short-term break in coverage wherein a beneficiary is

disenrolled from the program and then re-enrolled shortly thereafter (MACPAC 2021, Ku and Platt 2022, Zylla et

al. 2018).

In reducing churn, ex parte renewals may ultimately promote continuity of care for beneficiaries and

reduce costs for beneficiaries and states.

Promoting program integrity and reducing administrative burden for states. The use of electronic data

sources to verify eligibility can identify unreported income and reduce manual verifications. In some public

programs, electronic data verification has been used to improve program integrity and achieve administrative

efficiencies (GAO 2021).

Data Considerations with Ex Parte Renewals

Roundtable participants noted that the selection of data sources and the order in which these data are evaluated

has implications for the rate of successful ex parte renewals. When conducting ex parte renewals, states must

use reliable information that is available to the agency.

9

States have flexibility to determine which data sources

they consider to be most useful as well as the timeliness standards for those data (CMS 2020). As a result, the

specific data sources used and the priority of their review vary across states.

Accessing a variety of data sources to conduct ex parte renewals

Roundtable participants supported state use of a variety of data sources for ex parte renewals, noting that each

have advantages and limitations, and that some data sources are more important for conducting ex parte

renewals with certain Medicaid populations than others (Table A-1). Examples of electronic data sources that

states use to verify income eligibility include federal and state income tax information, unemployment insurance

information, quarterly wage reports, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Temporary

Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) data (CMS 2022a; Gordon et al. 2022). States also use asset verification

systems (AVS) to obtain information about the financial and nonfinancial assets of beneficiaries whose eligibility

requires an asset test. Although citizenship and immigration status typically do not need to be reviewed annually,

the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services SAVE database enables electronic verification of that information

(CMS 2022a). State participants generally described using at least one wage data source, one tax data source

(typically Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data), and SNAP data in their current ex parte renewal processes. A

policy expert also explicitly noted that states need to use more than one data source if they want to achieve a high

rate of successful ex parte renewals.

State decisions about which data to use for ex parte renewals are based on a number of factors, including the

ease of use, the number of cases to which the data are applicable, and the specificity of the data. Participants

noted a number of challenges related to accessing specific data sources. For example, most roundtable

participants agreed that IRS data can be challenging to use due to the additional steps to obtaining the data.

10

Roundtable participants noted several areas where returned data do not provide the level of specificity necessary

to make a determination. Specifically, when SNAP and Medicaid systems are not integrated, the Medicaid agency

might receive only summary income information through a data sharing agreement, rather than details on the type

of income and the household member who earned it which are needed to redetermine Medicaid eligibility

4

accurately. Participants also described how the lack of historic information and challenges understanding agency-

specific codes in Social Security Administration (SSA) data and the SAVE database can inhibit ex parte

renewals.

11

States also consider program integrity concerns alongside the goals of reducing burdens for both states and

beneficiaries in selecting data sources. Due to concerns about post-eligibility audits, states may opt to be more

stringent in their processes to ensure that they are adhering to audit requirements, for example, by following only

written guidance, as opposed to verbal direction from CMS. In addition, a beneficiary advocate noted the

implications of selecting particular data sources for the kinds of verification requests that might be sent to

beneficiaries if ex parte renewal processes are unsuccessful. For example, if a state uses IRS data that is two

years old, beneficiaries in that state may receive requests for information about income from jobs that they have

not had for two years.

Data hierarchies to prioritize sources and resolve conflicting information

Given the number of available data sources to verify beneficiary information, CMS has encouraged states to

develop data hierarchies to strategically check sources against eligibility criteria; however, building a data

hierarchy that works effectively for all Medicaid beneficiaries in a state can be challenging (CMS 2022a). Data

hierarchies can facilitate use of ex parte renewals in situations where different data sources contain conflicting

information, thereby decreasing unnecessary documentation requests for beneficiaries.

When states use data hierarchies, they may choose to review different data sources consecutively or

concurrently. A consecutive review is the review of all data sources and available information for a given eligibility

criterion, such as income, in a particular order. Once the household’s income is verified and found to be below the

Medicaid eligibility threshold, eligibility is verified and the data check is complete. In a concurrent review, a state’s

system reviews all data sources and available information simultaneously for a given eligibility criterion, such as

income. If any data source verifies eligibility, the state may consider the criterion verified (CMS 2022a).

Nearly all of the states that participated in the roundtable currently use data source hierarchies in conducting ex

parte renewals and almost all of those states use consecutive review processes. However, the data sources

included in the hierarchy and the order in which they are reviewed vary based on data availability and other policy

priorities. For example, one state without a state income tax begins the ex parte process by examining IRS data.

Several other states noted that IRS data is less useful because they have more recent state-level income data to

examine. In addition, the criteria for selecting the hierarchy order differs. For example, one state uses the age of

the data source to prioritize data sources, whereas another state focuses on the perceived accuracy of the data,

and a third prioritizes data sources based on the proportion of beneficiaries who can successfully be renewed

when each data source is used.

Another complicating issue is the fact that different data sources might be more important for certain beneficiary

populations than for others. For example, Social Security data might be especially important for non-MAGI

eligibility groups and IRS data might be important to verify the income of self-employed people. However, when

asked if they use different data source hierarchies for different populations of Medicaid beneficiaries, particularly

MAGI-based and non-MAGI eligibility groups, the majority of state participants reported that they do not.

Confusion regarding the application of reasonable compatibility

Federal regulations require states to compare electronic data sources to self-attested information provided by

Medicaid beneficiaries to determine whether the income data are reasonably compatible. Data are considered

reasonably compatible if both are either above or at or below the applicable income standard or other relevant

income threshold (42 CFR 435.952(c)(1)).

12

Roundtable participants identified confusion regarding the permissibility of using reasonable compatibility

standards during ex parte renewals. Several state and vendor participants acknowledged using reasonable

5

compatibility standards to compare data sources to existing information in the case file or the income threshold

during the ex parte process. However, a CMS official clarified that application of reasonable compatibility

standards requires a recent beneficiary attestation. During an ex parte renewal, a beneficiary does not provide

information and the attestation from the application or previous renewal would be considered too old to reference.

(Reasonable compatibility standards do apply during renewal in the event that an individual submits a renewal

form or responds to a request for income information.) The CMS official also acknowledged that the agency

intends to provide clarifying guidance and technical assistance to states on this topic.

Ex Parte Challenges for Particular Groups

Although states must attempt an ex parte renewal for all Medicaid beneficiaries, the process can be more

challenging with some populations than others, and historically, some states have excluded specific groups of

beneficiaries from the ex parte renewal process entirely. The challenges often arise because of the additional

eligibility factors that may need to be verified, such as assets or health and disability information, that may not

have easily accessed or available data. For example, as of 2019, Illinois could not process ex parte renewals for

several populations, including individuals with disabilities and those over the age of 65, as well as households

with no income and beneficiaries with self-employment income, due to data source limitations and other

challenges (IL DHS 2023, IL DHFS 2019).

13

Other states have also faced challenges in using ex parte renewals

with these populations (Grusin 2021, Wagner 2021, SHADAC 2020, Wishner et al. 2018).

Non-MAGI eligibility groups

Non-MAGI eligibility groups, which includes individuals who qualify on the basis of disability or age, typically have

additional factors of eligibility, such as asset limits and functional assessments that make ex parte renewals more

complicated. These beneficiaries are also more likely to have multiple chronic conditions, certain disabilities, or a

high likelihood of needing hospital or institutional care, all of which can make engaging in the redetermination

process difficult (Weir Lakhmani 2022).

Legacy eligibility systems prevent ex parte processes for non-MAGI groups in some states. In some

states, the inability to conduct ex parte renewals with non-MAGI eligibility groups is due to the continued use of

legacy eligibility and enrollment systems for these beneficiaries. These systems are not configured to process

renewals via ex parte methods with states foregoing such updates to outdated systems. Instead, most states

would prefer to build modern eligibility systems that have ex parte renewal capabilities or migrate non-MAGI

populations into newer systems configured for MAGI-populations in the wake of passage of the ACA. However, a

roundtable participant stressed the importance of states finding a way to conduct ex parte renewals with non-

MAGI groups, either by developing a manual process or by transitioning non-MAGI beneficiaries into an updated

eligibility system.

Verifying assets is the most common challenge with ex parte renewals for non-MAGI eligibility groups.

Limitations in the timeliness and availability of asset information in state AVS inhibit the use of ex parte renewals

for non-MAGI beneficiaries. Typically, individuals eligible on a non-MAGI basis must meet both income and asset

financial eligibility criteria to qualify for Medicaid. States must use an electronic AVS to verify assets for non-MAGI

populations, including during ex parte renewals (CMS 2022a, 2009). However, most states have only recently

implemented these systems. In 2018, 12 states did not yet have an AVS. In October 2020, four states did not

have an AVS and five states were partially out of compliance (MACPAC 2020). In addition, the data that can be

verified by these systems are limited, use of the systems can be challenging and time-consuming, and databases

may generate false matches. Costs of the systems can also be an issue for states as many AVS vendors charge

per individual processed (Musumeci et al. 2022, Erzouki and Wagner 2021).

• AVS data are frequently not returned in a timely enough fashion to support ex parte renewals for non-

MAGI beneficiaries. Roundtable participants noted that AVS responses can sometimes take up to 30 days,

that responses can be delayed, and that the data provided may not ultimately be from the most current

6

month. In some cases, results might need to be returned by fax or mail, which can take longer and be more

difficult for states to process automatically. These challenges seem to be more common with smaller banks

and credit unions than with larger institutions (Musumeci et al. 2022, Erzouki and Wagner 2021, MACPAC

2020).

• Limited AVS participation among financial institutions and gaps in the types of assets detected by

AVS require many non-MAGI beneficiaries to provide asset documentation. Financial institutions are not

required to report information on Medicaid applicants’ assets. When financial institutions refuse to participate

in an AVS, states might not be able to verify all asset information and have to ask beneficiaries to respond to

a renewal notice (MACPAC 2020). Roundtable participants mentioned that AVS participation is typically

limited to banks and credit unions. In addition, bank account information returned by AVS does not provide

the kind of transactional details necessary for states to determine whether any of the funds in a particular

account are from an income source that should be excluded.

14

Participants from two states also

acknowledged that a major challenge is verifying assets that the AVS cannot verify, either because the asset

is a type that is not in an AVS (e.g., life insurance) or because the asset is held by a non-participating bank.

As a result, the state must ask the beneficiary for documentation of those assets, which can be burdensome

for the beneficiary and often requires help from assisters or professional benefits counselors in gathering

documentation to comply with state requests. It can also result in loss of eligibility if the beneficiary cannot

comply with the state’s request.

• Beneficiary consent and inaccurate matches can also increase the burden of AVS. An IT vendor who

has worked with multiple states noted that some states have faced challenges using AVS with certain

beneficiary populations (particularly those who move from a MAGI eligibility group into a non-MAGI eligibility

group) due to a federal requirement that beneficiaries must consent to state use of AVS to verify assets.

15

In

addition, two states and a beneficiary advocate noted that false AVS matches, for example, from situations in

which a beneficiary is listed as a secondary name on an account, can result in inaccurate asset information

for beneficiaries. These inaccurate results can be particularly cumbersome to navigate, as it can be difficult

and time-consuming for beneficiaries to prove that they do not own specific assets. These inaccurate matches

can also lead to inappropriate loss of benefits in cases where misidentified assets appear to make the

beneficiary ineligible for Medicaid.

Despite the limitations of AVS, roundtable participants agreed that AVS is an important tool, as it is the only

means to electronically verify assets and process ex parte renewals for non-MAGI beneficiaries. Most participants

also agreed that ongoing exploration of ways to improve the asset verification process is important (Box 2).

Individuals with income that is difficult to verify electronically

Income verification remains a barrier for those with zero or unstable incomes, such as individuals who are self-

employed, seasonally employed, or frequently change jobs. In these cases, income may not be able to be

confirmed with electronic income data sources due to a lack of data, data lags, or other limitations (SHADAC

2020). Verifying zero income via electronic sources is particularly difficult because a lack of data cannot be

assumed to indicate that an individual does not have any income.

16

Verifying self-employment income is typically

done through state income tax or IRS data. However, roundtable participants confirmed that IRS data are often

one to two years old, so it can be of limited use when beneficiary circumstances have changed.

SNAP data can be used to conduct ex parte renewals with SNAP-enrolled households that have zero or self-

employed income (Wagner 2020).

17

Unlike other data sources, which only show that no information was found,

SNAP data can confirm that an individual has no income, as emphasized by one roundtable attendee. States

must typically reverify SNAP eligibility every six months, so the state will also have recent data from those

eligibility determinations. A state participant noted that the state’s integrated eligibility system facilitates verifying

zero income for households with SNAP. Notably, while SNAP data were described as a critical data source for

verifying zero income among households receiving SNAP, no participants mentioned using SNAP data to verify

self-employment income, although the data could be used in a similar fashion.

7

Beneficiaries who shift between eligibility groups

Several roundtable participants agreed that ex parte renewals are difficult to complete for beneficiaries who move

from one Medicaid eligibility group to another. In particular, one subject matter expert said that there are problems

in many states when Medicaid beneficiaries who are eligible through a Supplemental Security Income (SSI)-

based pathway lose SSI benefits. A CMS participant acknowledged that states may lack detailed information

about beneficiaries’ circumstances to conduct ex parte renewals.

18

In addition, roundtable participants also

specifically noted that ex parte renewals are often difficult or impossible to complete for beneficiaries who move

from MAGI eligibility groups to aged, blind, and disabled eligibility groups, largely due to the need to verify assets,

which MAGI beneficiaries would not have identified during their initial Medicaid application process. Moreover,

MAGI beneficiaries with disabilities who must move to a non-MAGI eligibility group may also require a disability

assessment, which cannot be completed on an ex parte basis.

One participant also noted that many states refrain from using ex parte processes with beneficiaries who are

subject to premiums when those individuals need to move to a higher premium level. Many states treat premium

bands as different eligibility categories, meaning that a move to a higher premium level ultimately requires use of

manual renewal instead of an ex parte renewal process. The participant also noted that in cases where the ex

parte process determines that the individual remains eligible for Medicaid in a less generous category, the state

should send out the prepopulated renewal form. If it is not returned, the state should move the individual into the

less generous category and provide sufficient notice to the beneficiary.

19

They also noted, however, that many

states had not yet addressed this long-standing programming issue that requires mandatory processing.

Barriers for beneficiaries for whom states must verify health or medical expense

information during renewal

Roundtable participants also named several groups for whom states must verify health status or medical expense

information during renewal periods as difficult to renew via ex parte methods. In particular, participants mentioned

breast and cervical cancer treatment groups (for whom states must verify ongoing need for this treatment), people

who are eligible for Medicaid based on a need for long-term services and supports (and require a level of care

assessment as part of their renewal process), and people who are eligible for Medicaid based on a disability and

are due for a medical or disability review.

20

Medically needy populations, who have income or assets that are over the eligibility thresholds but qualify for

Medicaid by spending down enough of their income or assets on medically related costs, were also noted as a

population for which ex parte renewals are difficult.

21

Existing data sources will not include the spend down

amounts and instead indicate that the beneficiaries’ income or assets make them ineligible. However, a policy

expert noted that one state had recently established a pilot that will identify people in the medically needy group

who have precise and verifiable income, such as Social Security income alone. In these cases, the spend-down

amount will be identified through the ex parte process and the state will send a notice to the individual indicating

the spend-down amount without the need for a manual renewal process.

Households with pending case actions

States have historically used pending action flags in situations, such as a recently-reported income change, to

prevent that person from going through an ex parte renewal while there is something in process on the case.

These flags can create challenges for ex parte renewal processes, as they prevent some states from conducting

a renewal for the entire household if one individual in the household has a flag present. A policy expert said they

have seen an increase in the volume of these cases during the unwinding of the continuous enrollment condition.

They also noted that given the length of the PHE, these flags may no longer indicate a recent change, but may

still prevent a large number of cases from going through ex parte processes. Several state participants reported

this is a current problem in their states, to varying degrees.

8

Systems Factors Limiting Ex Parte Renewals

In general, roundtable participants agreed that policy decisions, data sources, and data access challenges play a

more substantial role in the success of ex parte processes than IT or systems issues. The primary IT-related

factors that participants described as affecting states’ ex parte processes were states’ IT resources and priorities,

and the extent to which states’ Medicaid eligibility systems are integrated with eligibility systems used for other

human services programs, such as SNAP or TANF.

22

Although automation was not cited as increasing the

accuracy or success rates of ex parte renewals, several participants agreed that automation improves efficiency

in ex parte processes.

IT resources and competing priorities

Both state and non-state roundtable participants agreed that Medicaid agencies’ ex parte efforts are less likely to

be hindered by technological limitations than they are by limited resources and competing priorities. States have

limited resources to make IT changes and upgrades, necessitating state agencies to set IT priorities. Budget

constraints can limit states’ ex parte process enhancements or the speed with which states can implement

them.

23

Participants agreed that generally vendors can program any changes requested by the state, although

some changes might be easier and less expensive to make than other changes that require extensive

programming. Yet even small upgrades require time and money for planning, development, and testing to ensure

that new programming does not negatively impact other systems functions. For example, one state participant

said they do not deploy systems changes during open enrollment because their eligibility system is integrated with

their state-based exchange, and they cannot risk having systems failures or defects during that time.

Competing priorities can slow down activities to improve use of ex parte renewals. States are limited in the

number of changes they can make to their systems at one time and must account for other priorities, such as

updates required by legislation, litigation, or the adoption of new programs. The number of upgrades a state can

implement in a particular year may also be reduced if states need to stop systems development during certain

parts of the year, as noted above. Additionally, when considering enhancements to an IT system, states must

weigh the short- and long-term costs and benefits of such changes. For example, several state participants noted

that the temporary nature of the Section 1902(e)(14) flexibilities was an important consideration in deciding

whether to adopt them.

Integration of eligibility systems

One of the primary IT factors affecting ex parte renewals is whether a state’s eligibility system is integrated with

other human services programs, such as SNAP or TANF.

24

States with integrated eligibility systems have access

to updated information from the individual’s SNAP renewal, which may streamline the process. In states where

the Medicaid eligibility system is not integrated with other human service programs, access to usable data can be

hampered by bureaucratic processes and incomplete data. Specifically, Medicaid agencies require a data sharing

agreement to obtain and use data from those human services agencies for purposes of ex parte renewals.

Participants from two states acknowledged that these data sharing agreements have been barriers in the past. As

noted above, in states without integrated eligibility systems, Medicaid agencies may receive a total income value

from their data exchanges with SNAP agencies, without specific information about the income sources or the

household members who earned it. Thus, Medicaid agencies might not be able to determine the extent to which

the income reported for SNAP aligns with the Medicaid income and household definitions.

Unintended consequences from using data in integrated systems can negatively affect beneficiaries’ eligibility. For

example, a lack of adequate caseworker training or automated systems that are not programmed to implement

policy correctly could affect eligibility determinations. A beneficiary advocate and a policy expert each noted that

because SNAP recertifications are conducted every six months, they may inappropriately trigger a Medicaid

renewal on the same timeline. Another policy expert agreed, stating that they heard of cases where individuals

who fail to return their SNAP renewal are terminated from all benefit programs, including Medicaid. Both issues

may be the result of policy, operational, or IT system programming issues.

9

Use of automation in ex parte renewals

States vary widely in their use of automated ex parte renewals. Some states use fully automated data checks, in

which computer programs automatically connect to electronic data sources and compare results to the applicable

income and asset thresholds. However, full automation is not required to achieve a high rate of ex parte renewals.

Some states using a combination of manual and automatic procedures have been able to renew more than 50

percent of their Medicaid beneficiaries via ex parte processing (Brooks et al. 2023).

Automating ex parte renewal processing can free up staff time for other eligibility-related tasks, such as

processing renewal forms completed by beneficiaries whose eligibility could not be renewed on an ex parte basis

or responding to new applications. Moreover, increasing automation can reduce the amount of training required to

ensure that eligibility case workers understand complex renewal processes, which typically demands significant

time and investment, especially during periods of high staff turnover. When asked whether automation impacts

either the success or the accuracy of ex parte renewals, two state participants and a representative from CMS

said that they did not think there was a noticeable difference in the accuracy of renewals processed automatically

and renewals processed manually.

Conversely, one state participant acknowledged that, with greater automation, it often takes more time to identify

defects within the system than it did with manual processes, when case workers were monitoring the process at

all times. Similarly, a few state participants described longer delays in implementing systems changes related to

automated ex parte renewal processing, compared to the timeline for implementing changes in manual systems.

As such, states with manual ex parte processes may be able to adopt new procedures more quickly than states

with automated processes, for which the time to configure and test new settings can cause delays.

Opportunities for Improvement

Participants identified potential opportunities for states, CMS, and IT system vendors to improve ex parte

renewals.

25

Suggestions centered around several key areas, including increasing transparency and providing

opportunities for shared learning. Specifically, several suggestions focused on making ex parte processes and

data public with the goal of improving procedures and allowing states to learn from each other. In addition, further

guidance, technical assistance, and oversight could ensure compliance and identify opportunities for

improvement.

Increased data and process transparency

Roundtable participants suggested that states should make ex parte policies and processes, including system

logic and successful strategies and mitigation plans, publicly available. They also suggested that IT vendors could

better support states by making ex parte rules and logic public. In addition, participants raised the idea of

leveraging solutions built for one state in other states and enabling states to make more system changes on their

own, which could expedite implementation timelines and reduce costs. The participants who made these

suggestions believed that this kind of public information sharing could be an important tool in helping states, CMS,

and other stakeholders, such as advocates, understand ex parte processes and approaches and identify changes

states could make to improve ex parte rates.

Participants also suggested that ex parte renewal data continue to be published after the unwinding period ends,

and that additional data, such as ex parte rates by eligibility category, should be shared. Participants noted that

both states and CMS play a role in increasing transparency around ex parte renewals. Specifically, participates

highlighted the need for states to share these data, as well as for CMS to require ongoing reporting and

publication at a national level. Additionally, CMS participants encouraged states to share data on the effects of

Section 1902(e)(14)(a) waivers on ex parte rates in particular to assist the agency in assessing which flexibilities

may be worth trying to preserve.

10

Assessment and oversight of current processes

Participants also suggested that states should evaluate whether their current policies and systems configurations

comply with federal and state rules and identify opportunities for improvement. For example, one participant

mentioned that states should conduct a careful walk-through of IT systems and implementation of ex parte

business rules to ensure full compliance with federal and state policies. Another mentioned that states could

conduct diagnostic evaluations to assess whether and what additional data sources or business rules could be

put in place to increase ex parte rates. A third suggested that states could examine data and ex parte failure

reasons, presumably to identify options for data sources that might be leveraged to avoid those failures in the

future. Another suggested said that states and vendors could engage beneficiaries and advocates to develop test

cases, with the goal of identifying ways to improve systems and business rules.

Some participants recommended that CMS conduct additional oversight of states’ ex parte processes to ensure

that state systems do not conflict with federal requirements and state policies, as well as to promote greater

accountability for states with particularly low ex parte renewal rates. For example, participants suggested

implementing corrective action plans for states that do not have ex parte processes in place or that have high

rates of procedural terminations.

26

Participants also suggested establishing minimum acceptable ex parte rate

thresholds, such that states with rates below the threshold will be susceptible to a closer review.

Guidance and technical assistance

Participants also indicated that CMS should provide additional and clearer guidance for states. For example, CMS

identifying the types of assets that are not likely to appreciate and notifying states that they do not need to verify

those assets annually generated significant interest (Box 2). Additionally, a participant suggested that federal

guidance on ex parte requirements for when someone is transitioning between eligibility categories would be

helpful, and another participant agreed. Two participants suggested that CMS should consider whether

reasonable compatibility thresholds could be incorporated into ex parte renewals.

Beyond guidance and oversight, participants requested that CMS provide additional technical assistance to states

on topics related to ex parte renewals, including intensive technical assistance to states with low ex parte rates

and the use of specific data sources, such as SNAP data.

Participants also indicated interest in sharing examples of successful state practices and facilitating opportunities

for collective information sharing and learning across states. For example, CMS could share examples of state

practices that promote successful ex parte renewals or host convenings that allow states to hear what others are

doing and to collaborate on identifying additional solutions. Another participant suggested that vendors could

sponsor or facilitate meetings for states they serve.

Making unwinding-related flexibilities permanent

Participants encouraged the federal government to consider making the flexibilities allowed during the unwinding

period under Section 1902(e)(14)(a) waivers permanent. Throughout the roundtable discussion, several

participants emphasized the value of these waivers, specifically with regard to enabling streamlined processes for

asset verification, ex parte renewals for individuals with zero income, and the use of SNAP eligibility information

for ex parte renewals. One participant also suggested that CMS could simplify the approach used under the

SNAP state plan amendment to align more with the current Section 1902(e)(14)(a) waiver process.

27

11

BOX 2. Specific opportunities for addressing asset verification challenges

Given the significant challenges that states face in verifying assets, roundtable participants identified a number of

specific opportunities for improvement.

Roundtable participants emphasized the value of the Section 1902(e)(14)(a) waiver flexibilities to

streamline or waive asset verification during the unwinding of the continuous coverage requirement. One

temporary waiver option allows states to renew coverage for non-MAGI beneficiaries on an ex parte basis if the

state’s asset verification system (AVS) does not return information in a timely fashion. Another temporary

approach enables states to waive consideration of assets only during renewal. As of July 27, 2023, 21 states

have adopted the option to renew individuals when the AVS does not produce a timely response and 5 states

have received approval to waive consideration of some or all assets at renewal (CMS 2023c).

28

An information

technology (IT) vendor, multiple policy experts, beneficiary advocates, and all of the state participants expressed

support for these waivers. One state participant with a waiver to renew coverage if the state’s AVS does not

return timely information said that this waiver has helped the state increase its ex parte renewal rate with non-

MAGI beneficiaries from 40 percent to approximately 80 percent in May and June of 2023.

States can also use existing authorities to increase asset limits or waive consideration of assets in

standard Medicaid application and renewal processes. States can use authority under Section 1902(r)(2) of

the Social Security Act to increase or waive asset limits more broadly. However, this authority requires that states

apply asset requirements consistently during application and renewal processes, rather than solely at renewal as

allowed under the temporary waivers.

29

At least one participant representing an IT vendor supported the idea of

states broadly waiving asset consideration, noting that in their 30-years of experience working in Medicaid and

human service program delivery, the process of verifying assets requires considerable effort and that individuals

are rarely determined ineligible because of their assets but because they are not able to verify their assets.

Participants requested that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) provide clearer guidance

about the types of assets that are unlikely to appreciate and would not need to be reverified. The AVS can

verify only a small portion of potential assets that Medicaid beneficiaries may hold. As a result, states require

beneficiaries to provide documentation, especially for individuals who have non-liquid assets. Several

participants, including policy experts, beneficiary advocates, and state participants, said that it would be helpful if

CMS could provide written guidance that identifies the types of assets that are unlikely to appreciate over time

and explains that states do not need to reverify those assets during annual renewals.

30

A beneficiary advocate

noted that similar guidance has been very helpful in preventing states from reverifying citizenship annually.

Endnotes

1

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA, P.L. 116-127) provided states with a temporary 6.2 percentage point

increase in the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) if they met certain conditions, including a continuous coverage

requirement for most Medicaid beneficiaries who were enrolled in the program as of or after March 18, 2020. The continuous

coverage requirement was in place through the end of the month in which the public health emergency (PHE) ends. The

FMAP increase was available through the end of the quarter in which the ends.

Enacted in December 2022, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (CAA, P.L. 117-328) decoupled the end of the

continuous coverage requirement from the PHE and established an end date of March 31, 2023 for the requirement. In

addition, the CAA phased down the enhanced matching rate over the remainder of 2023, if states meet certain data reporting

and renewal processing requirements, including conducing ex parte renewals (CMS 2023a).

2

The roundtable was held on June 27 and 29, 2023, and included state Medicaid agency staff from six states, two staff from

CMS, and seven subject matter experts. The six states represented diverse political affiliations and geographies, as well as

12

differences in ex parte renewal rates, recent efforts to improve ex parte renewals, and system integration, among other policy

factors. Subject matter experts included beneficiary advocates, policy experts, program integrity experts, and information

technology (IT) system vendors.

3

Information from the individual’s initial determination at application or the beneficiary’s last renewal is not considered recent

or reliable, unless it relates to a circumstance generally not subject to change. Eligibility criteria for which a beneficiary’s

information is not generally subject to change, such as blindness, does not need to be re-verified during a renewal (CMS

2020).

4

Section 1137 of the Social Security Act has long required states to use income and eligibility verification systems to access

information from the Social Security Administration (SSA), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), state unemployment agencies,

and employer quarterly wage reports for the purpose of verifying Medicaid eligibility, but those requirements do not specifically

require use of ex parte processes for eligibility renewal. However, CMS did issue subregulatory guidance before the passage

of the ACA, describing its expectations that states use ex parte renewal processes whenever possible (HCFA 2000).

5

Section 1413(c)(3)(ii) of the ACA requires states to “determine…eligibility [for Medicaid] on the basis of reliable, third-party

data, including information described in sections 1137, 453(i), and 1942(a) of the Social Security Act.” CMS codified the ex

parte regulations in a final rule issued in the Federal Register on March 23, 2012 (CMS 2012).

6

MAGI-based methods are used to determine income eligibility for most Medicaid beneficiaries, including children, pregnant

people, parents, and adults under age 65 without dependent children. Eligibility groups for whom income eligibility is

determined using other (non-MAGI) methods include those who are eligible based on age or disability, those whose eligibility

for Medicaid does not require a Medicaid determination of income, such as individuals receiving Supplemental Security

Income or Title IV-E child welfare assistance; those in need of long-term services and supports; and certain individuals

applying for assistance with Medicare cost sharing or through medically needy pathways (42 CFR 435.603).

7

During the unwinding of the continuous coverage requirement, states must report the number of beneficiaries renewed via ex

parte, although they do not need to differentiate rates by population (CMS 2022b).

8

CMS has shared several guidance documents and training resources for states related to the unwinding of the continuous

coverage provision (CMS 2023c). In addition, CMS has also released specific information on ex parte renewals, including a

letter to states regarding the need to conduct ex parte renewals at the individual level and a review of the renewal

requirements (CMS 2023d, 2020). CMS also conducted a training for states on ex parte renewal on October 20, 2022 (CMS

2022a).

9

CMS views data as reliable if they have been verified in the past six months or at any time if the data are not likely to change

(CMS 2022a).

10

States must obtain and renew beneficiary consent to use IRS data. Additionally, one state said that they have to submit

requests for data matching to the IRS at least 30 days in advance of the ex parte renewal, then store the data in a staging

table in advance. Some participates also reported that use of IRS data in ex parte renewals can generate frustration when

auditors want to review the actual data returned by the IRS, which the state Medicaid agency cannot share due to data use

restrictions.

11

For example, several state participants commented that federal SSA databases do not contain historical data on individuals’

receipt of certain Social Security benefits, which is needed for certain groups whose eligibility is based on their receipt (or a

parent’s receipt) of these benefits. Similarly, a beneficiary advocate explained that the SAVE database only contains a

beneficiary’s current immigration status. This is problematic in cases when a beneficiary’s immigration status changes. For

example, if a refugee gains legal permanent residency status, they should remain exempt from the five-year waiting period.

Because SAVE does not retain prior immigration status information, it cannot be used alone to conduct ex parte renewals for

these beneficiaries.

12

States may also establish their own reasonable compatibility standards for an acceptable level of difference, either as a

percentage of income or a specific dollar amount (CMS 2013). About two-thirds of states have established a reasonable

compatibility threshold with the majority using a percentage threshold, most often 10 percent (Brooks et al. 2020).

13

13

With the establishment of an AVS, non-MAGI populations can now be renewed via ex parte methods in Illinois (IL DHS

2023).

14

For example, the recovery rebates authorized by section 2201 of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security

(CARES Act, P.L. 116-136) are not considered income for the purpose of Medicaid financial eligibility determinations, nor

could the income from these payments be considered an asset in the first 12 months after receipt (CMS 2021a).

15

If the information obtained through AVS will be retained by the state, for example, in the beneficiary’s case file, beneficiary

consent is statutorily required. Most states collect this consent at the time of application. However, if an individual is moving

into a non-MAGI group from a group whose eligibility is based on MAGI, consent to check AVS would not have been

previously obtained as assets are not an eligibility criterion for MAGI populations.

16

CMS informally advised Idaho and Illinois that finding no income information in electronic data sources was not sufficient

verification of zero income (Wagner 2020, 2021; IL DHFS 2019).

17

During the unwinding, CMS has given states the option to complete ex parte renewal for individuals with no income, when

no data are returned. As of July, 23, 2023, 37 states have received approval for this §1902(e)(14)(A) waiver option (CMS

2023b).

18

States have the choice of using the SSI eligibility criteria for Medicaid eligibility or implementing more restrictive criteria to

determine Medicaid eligibility (referred to as 209b states). States that use the SSI eligibility criteria can make their own

determinations or allow SSA to determine eligibility on behalf of the state (known as 1634 states). These 1634, in particular,

may lack the detailed information about beneficiaries’ circumstances to conduct ex parte renewals as Medicaid agencies do

not receive information beyond the fact that the individual is no longer SSI-eligible.

19

CMS describes this process for individuals shifting premium bands in the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

(CMS 2022d).

20

Disability reviews are not required annually, but are often time-consuming when they are required, as the beneficiary must

demonstrate their ongoing disability through multiple forms of documentation. One participant noted that these reviews may be

required at renewal when a beneficiary needs to move from a MAGI eligibility group into a disability-based group.

21

States can choose to cover individuals with high medical expenses. Referred to as medically needy individuals, this pathway

can include those age 65 and older, individuals with disabilities, as well as parents, pregnant women, and children that would

be categorically eligible, except for their incomes. The medical expenses incurred (also referred to as spend down) are

deducted from income for purposes of determining eligibility (42 CFR 435.300-335).

22

During a discussion of county vs. state-based processing of eligibility renewals, participants did not express strong opinions

about this playing a major role in processing ex parte renewals. For example, one state attendee with a county-based system

noted that ex parte renewals are automated, with county workers only taking over cases after renewal forms are mailed. A

policy expert noted that if ex parte renewals are largely automated, there should not be much variation across counties in how

they are handled. In states where the county ex parte rates vary, the expert speculated that state oversight could be a

challenge when the renewal process is diffused across so many different counties.

23

States receive 90 percent federal match for systems design and development spending and a 75 percent federal match for

maintenance and operations spending (CMS 2015a).

24

Participants did not identify integration with the state’s exchange as relevant to their ability to conduct Medicaid ex parte

renewals. Instead, states agreed that integration of Medicaid and exchange eligibility information can affect processes for

beneficiaries and applicants who are deemed ineligible for Medicaid and need to obtain exchange coverage.

25

Some of these opportunities for improvement, such as reviewing business rules, logic and operational procedures, have

been noted in existing CMS technical assistance materials (CMS 2022a).

14

26

Participants also suggested that states could suspend procedural terminations until ex parte rates are at acceptable levels.

In June 2023, CMS released guidance with strategies states may adopt to minimize terminations for procedural reasons during

the COVID-19 unwinding period. One of the strategies that states may request is delaying procedural terminations for

beneficiaries for one month while the state conducts targeted renewal outreach during the unwinding of the continuous

enrollment condition (CMS 2023e).

27

States can establish express lane eligibility or apply for a facilitated enrollment state plan amendment to use high-level

SNAP income information to establish and renew eligibility (Wagner 2020, Manatt Health 2016, CMS 2015b). However,

roundtable participants said operationalizing these options is more complex than implementing a §1902(e)(14)(a) waiver,

which may be a barrier to adoption.

28

Four states (California, Maryland, Nevada, and Rhode Island) have been given authority to waive the beneficiary asset test

at renewal for individuals enrolled on a non-MAGI basis. New Hampshire’s waiver allows the state to assume there has been

no change in resources for non-MAGI individuals, which cannot be verified through the AVS, when the state has information in

the case file that the total countable resources, excluding trusts, are $999.99 or less (CMS 2023b).

29

Specifically, using Section 1902(r)(2) authority, states may elect to disregard all or a certain portion of household resources

that would otherwise be counted when determining eligibility for non-MAGI individuals (CMS 2021b).

30

In an October 2022 response to a list of frequently asked questions, CMS noted some assets are unlikely to appreciate in

value over time and that some are likely to depreciate in value and provided some examples (e.g., a second vehicle, most

personal property, burial funds, and some life insurance policies). However, CMS noted that the list was for illustrative

purposes only and that states have discretion to determine what types of assets are unlikely to increase appreciably in value

for purposes of conducting an ex parte renewal (CMS 2022c).

References

Brooks, T., A. Gardner, A. Osorio, et al. 2023. Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies as states

prepare for the unwinding of the pandemic-era continuous enrollment provision. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-and-renewal-policies-as-states-prepare-for-the-

unwinding-of-the-pandemic-era-continuous-enrollment-provision/.

Brooks, T., L. Roygardner, S. Artiga, et al. 2020. Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, and cost sharing as of January

2020: Findings from a 50-State Survey. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-cov

id-

19/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2020-findings-from-a-50-state-

survey/.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023a. Letter from Daniel

Tsai to state health officials regarding “Medicaid continuous enrollment condition changes, conditions for receiving the FFCRA

temporary FMAP increase, reporting requirements, and enforcement provisions in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023.”

January 27, 2023. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-02/sho23002_2.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023b. COVID-19 PHE

unwinding section 1902(e)(14)(A) waiver approvals. https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-s

tates/coronavirus-disease-2019-

covid-19/unwinding-and-returning-regular-operations-after-covid-19/covid-19-phe-unwinding-section-1902e14a-waiver-

approvals/index.html.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023c. Unwinding and

returning to regular operations after COVID-19. https://www.medicaid.gov/resources-for-st

ates/coronavirus-disease-2019-

covid-19/unwinding-and-returning-regular-operations-after-covid-19/index.html.

15

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023d. Letter from Daniel

Tsai to state health officials regarding “requirements to conduct Medicaid and CHIP renewal at the individual level.” August 30,

2023. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-08/state-ltr-ensuring-renewal-compliance.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023e. Available state

strategies to minimize terminations for procedural reasons during the COVID-19 unwinding period, June 2023. Baltimore, MD:

CMS. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-06/state-strategies-to-prevent-procedural-terminations.pdf

.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022a. Ex parte renewal:

Strategies to maximize automation, increase renewal rates, and support unwinding efforts. Baltimore, MD: CMS.

https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/ex-parte-renewal-102022.pdf

.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022b. Medicaid and

Children’s Health Insurance Program eligibility and enrollment data specifications for reporting during unwinding: Updated

December 2022. Baltimore, MD: CMS. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/unwinding-data-specifications-dec-

2022.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022c. COVID-19 public

health emergency unwinding frequently asked questions for state Medicaid and CHIP agencies, October 17, 2022. Baltimore,

MD: CMS. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/covid-19-unwinding-faqs-oct-2022.pdf

.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022d. Supporting

seamless coverage transitions for children moving between Medicaid and CHIP in separate CHIP states, December 12, 2022.

Baltimore, MD: CMS. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/supporting-medicaid-chip-transitions.pdf

.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2021a. COVID-19

frequently asked questions (FAQs) for state Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) agencies. Updated

January 6, 2021. Baltimore, MD: CMS. https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/covid-19-faqs.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2021b. Implementation

guide: Medicaid state plan eligibility: Less restrictive resource methodologies under 1902(r)(2). Baltimore, MD: CMS.

https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2021-01/macpro-ig-less-restrictive-resource-methodologies-1902r2.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. Center for Medicaid

and CHIP Services informational bulletin regarding “Medicaid and CHIP renewal requirements.” December 4, 2020.

https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib120420.pdf

.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015a. Medicaid program:

Mechanized claims processing and information retrieval systems (90/10). Final rule. Federal Register 80, no. 233 (December

4): 75817– 75843. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2015-12-04/pdf/2015-30591.pdf

.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015b. Letter from Vikki

Wachino to state health officials and state Medicaid directors regarding “Policy options for using SNAP to determine Medicaid

eligibility and an update on targeted enrollment strategies.” August 31, 2015.

https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-guidance-documents/SHO-15-001_154.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2013. Verification plan

template - guidance and instructions, phase I – MAGI-based eligibility. https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2019-

12/verification-plan-template-instructions.pdf.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2012. Medicaid program:

Eligibility changes under the Affordable Care Act of 2010. Final rule. Federal Register 77, no. 57: 17144-17217.

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2012-03-23/pdf/2012-6560.pdf

.

16

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2009. Letter from Bill

Brooks to state agencies administering approved medical assistance plans regarding “Asset Verification System (AVS)

requirements – Section 1940 of the Social Security Act.” January 15, 2009.

https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-gui

dance-

documents/2009.asset%2520verification%2520system%2520requirements%2520.pdf.

Deloitte. 2017. Arkansas Department of Human Services (DHS) questions for Deloitte. New York, NY: Deloitte. https://ssl-dfa-

site.ark.org/images/uploads/osp-anticipation-to-award/SP_17_0012_Deloitte_PresDoc2.pdf.

Erzouki, F., and J. Wagner. 2021. Using asset verification systems to streamline Medicaid determinations. Washington, DC:

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/using-asset-veri

fication-systems-to-streamline-

medicaid-determinations.

Grusin, S. 2021. A promise unfulfilled: Automated Medicaid eligibility decisions. National Health Law Program Blog, June 30.

https://healthlaw.org/a-promise-unfulfilled-automated-medicaid-eligibility-decisions/.

Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2000. Letter from Timothy M.

Westmoreland to state Medicaid directors regarding “Efforts to improve eligible families’ ability to enroll and stay enrolled in

Medicaid.” April 7, 2000. https://downloads.cms.gov/cmsgov/archived-downloads/SMDL/downloads/smd040700.pdf.

Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services (IL DHFS). 2019. Ex parte renewal report, as required by Public Act

101-0209. Springfield, IL: Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services.

https://mobile.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoDownloadDocument?pubId=&eodoc=true&documentID=6078.

Illinois Department of Human Services (IL DHS). 2023. Memo regarding “Continuous coverage ends 3/31/23 and Medical

redeterminations resume.” April 13, 2023. https://www.dhs.state.il.us/page.aspx?item=147233.

Manatt Health. 2016. Using Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) information to facilitate Medicaid enrollment

and renewal. Princeton, NJ: State Health and Value Strategies (SHVS). https://www.shvs.org/wp-

content/uploads/2016/09/State-Network-Manatt-Using-SNAP-Information-to-Facilitate-Medicaid-Enrollment-and-Renewal-

September-2016.pdf.

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). 2020. State compliance with electronic asset verification

requirements. Washington, DC: MACPAC. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-co

ntent/uploads/2020/10/State-Compliance-with-

Electronic-Asset-Verification-Requirements.pdf.

Musumeci, M., M. O’Malley Watts, and M. Ammula. 2022. Medicaid public health emergency unwinding policies affecting

seniors and people with disabilities: Findings from a 50-state survey. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-public-health-emergency-unwinding-policies-affecting-seniors-people-with-

disabilities-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/.

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NC DHHS). 2023. State report on plans for prioritizing and

distributing renewals following the end of the Medicaid continuous enrollment provisions. Raleigh, NC: NC DHHS.

https://medicaid.ncdhhs.gov/documents/medicaid/nc-plan-prioritizing-and-distributing-renewals-feb-15-2023/download

.

Ohio Department of Medicaid (ODM). n.d. Budget of the state of Ohio, FY 2024-2025: A return to routine eligibility operations.

Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Medicaid.

https://medicaid.ohio.gov/static/About+Us/Budget/Unwinding+from+the+Public+Health+Emergency+Whitepaper.pdf.

Purpure, D. 2019. Medicaid: Compliance with federal eligibility requirements. Presentation before the U.S. Senate Committee

on Finance, Subcommittee on Health Care, Washington, DC, October 30, 2019.

https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/30OCT2019PurperaSTMNT.pdf.

17

SHADAC. 2020. Addressing persistent Medicaid enrollment and renewal challenges as rolls increase. SHADAC Blog,

September 2. https://www.shadac.org/news/addressing-persistent-medicaid-enrollment-and-renewal-challenges-rolls-increase.

SHADAC. 2018a. Assessment and synthesis of selected Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and renewal processes and systems

in six states. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) contractor report. Washington, DC: MACPAC.

https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Assessment-and-Synthesis-of-Selected-Medicaid-Eligibility-Enrollment-

and-Renewal-Processes-and-Systems-in-Six-States.pdf.

SHADAC. 2018b. Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and renewal processes and systems study: Case study summary report—

Arizona. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) contractor report. Washington, DC: MACPAC.

https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Arizona-Summary-Report.pdf

.

Wagner, J. 2021. Streamlining Medicaid renewals through the ex parte process. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and

Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/3-3-21health.pdf.

Wagner, J. 2020. Using SNAP data for Medicaid renewals can keep eligible beneficiaries enrolled. Issue brief. Washington,

DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/using-snap-data-for-me

dicaid-renewals-can-

keep-eligible-beneficiaries-enrolled.

Weir Lakhmani, E. 2022. When the public health emergency ends what will it mean for dually eligible individuals? Health

Affairs Forefront, April 8. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/public-heal

th-emergency-ends-mean-dually-eligible-

individuals.

Wishner, J., I. Hill, J. Marks, and S. Thornburgh. 2018. Medicaid real-time eligibility determinations and automated renewals:

Lessons for Medi-Cal from Colorado and Washington. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98904/medicaid_real-

time_eligibility_determinations_and_automated_renewals_1.pdf.

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2021. Federal low-income programs: Use of data to verify eligibility varies

among selected programs and opportunities exist to promote additional use. Report No. GAO-21-183. Washington, DC:

https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-183

.

United States Social Security Administration (SSA). 2023. Data exchange applications.

https://www.ssa.gov/dataexchange/applications.html.

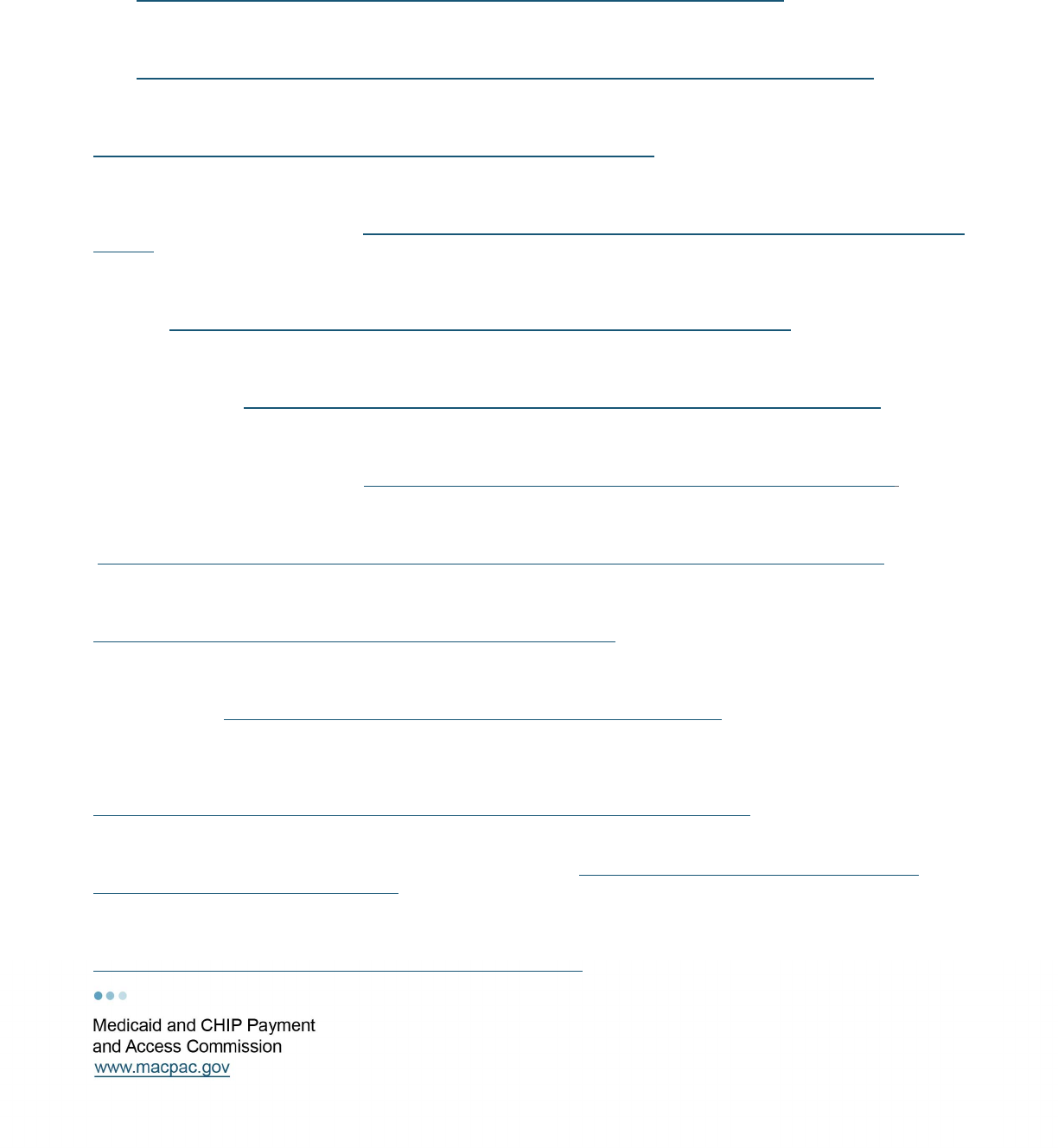

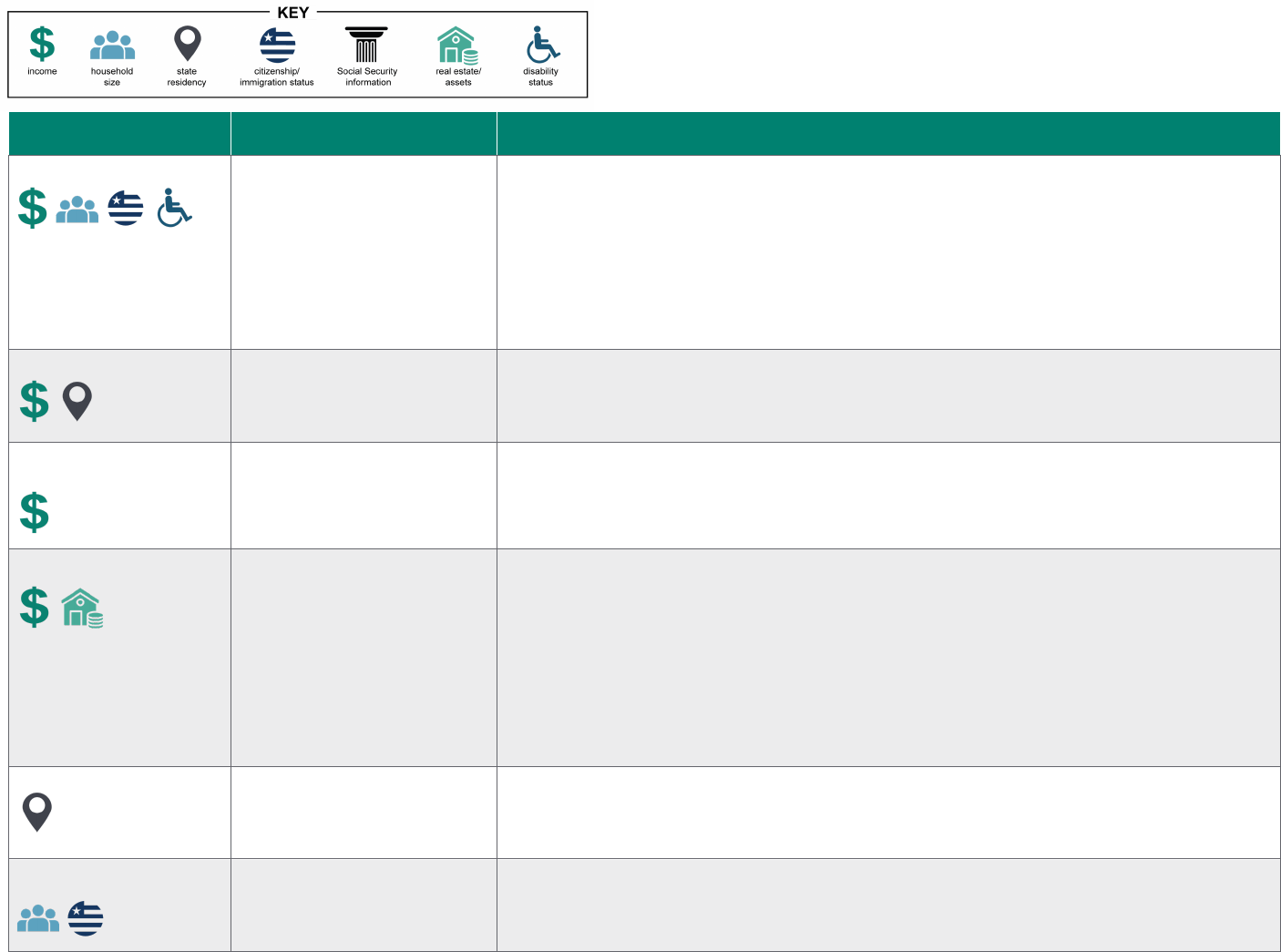

APPENDIX A: Ex Parte Data Sources

TABLE A-1. Select features and limitations of using certain data sources for ex parte renewals

Data source Features Limitations

Federal (IRS) and state tax

records

• Income available for self-

employed individuals

• Includes changes in

household composition

• May not reflect current income (e.g., IRS data are often two years old)

• Requests for IRS data must be submitted well in advance

• IRS data requires beneficiary consent, which must be renewed every five years

• States are not permitted to share IRS data with auditors

• Strict security requirements can impede connections and testing prior to launching data exchange

SWICA (i.e., quarterly wage

databases)

• More timely data than tax

records

• Does not reflect household composition changes

• Does not include data for self-employed individuals or income earned in other states

• May be less current or reported less frequently than The Work Number/TALX data

• Does not include current employment status or employment start or termination dates

The Work Number/TALX

• Possibly more current and

detailed than quarterly wage

data

• Does not include data for self-employed individuals

• Not all employers submit data and the share of a state’s Medicaid population with data in TALX varies

• Currently available through the FDHS, but states will have to pay for access in the future

• Data cannot be shared with other programs, such as SNAP

SSA data exchange

applications

• Can verify several eligibility

factors

• Can establish real-time,

automated data connections

• Legacy Medicaid eligibility systems may be unable to connect and verify Social Security benefits,

which are common among non-MAGI beneficiaries

• May not have information on historical receipt of SSI, which is necessary for establishing eligibility for

certain Medicaid eligibility groups

• SSA-specific codes can be unfamiliar to Medicaid eligibility workers

19

Data source Features Limitations

SNAP data

• Can verify several eligibility

factors

• Data are typically current

• Information available for

households with zero or self-

employment income

• Not all Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in SNAP

• In states with integrated eligibility systems, SNAP recertifications may trigger Medicaid

redeterminations

• In states without integrated eligibility systems, data use agreements must be established and the

SNAP data may not be detailed enough to determine Medicaid eligibility

• May be prone to error in states where SNAP case workers manually enter information and experience

high turnover rates

State unemployment data

• Includes unemployment

income

• Unknown

State public retiree system

data

• Includes retirement (pension)

income for retired public

employees

• Data are limited to former public employees

State AVS

• Only electronic source for

assets

• Participation is generally limited to a subset of banks and credit unions

• Cannot verify several types of assets, such as life insurance policies or stocks

• Responses can be delayed and the data may not be current

• Can sometimes return false matches, which can be difficult to disprove